It’s perhaps futile to try and squeeze the full breadth of British playwright and filmmaker David Hare’s magnificent career into a few short paragraphs. The man has done it all (and, as you’ll read below, he has the stories to prove it). A legend of British theatre, Hare’s extensive oeuvre needs no introduction, having won acclaim and accolades for his plays Plenty (1978), Skylight (1995), and Amy’s View (1997) (to name a few). He’s proved himself repeatedly as one of our most trusted voices, from his breakthrough play Slag (1970), a satire which the young writer reportedly wrote in three days from the back of a van, to Beat The Devil (2020), starring Hare-mainstay Ralph Fiennes, a fiery monologue piece chronicling Hare’s harrowing personal experience with COVID-19—in the process directing his ire at the British government for their disastrous response to the pandemic. His first play, though, was the one-act How Brophy Made Good (1969), which Hare wrote in “a ridiculous 96-hour dash”. A young Cambridge graduate at the time, he was director of the touring theatre company Portable, and was forced to write the play in only four days after a commissioned writer failed to deliver a script in time for rehearsals.

For all his monumental contributions to theatre—and monumental is not used lightly here—on this occasion, it’s screenwriting that’s on Hare’s mind, and it’s around screenwriting that he suggested his conversation with A Rabbit’s Foot Editor-in-Chief Charles Finch should revolve. Sometimes under the moniker of director, always as a screenwriter, Hare’s filmography is just as worthy of analysis and speculation as the theatrical work that launched his career. His first screenwriting credit was a 1985 adaptation of his own play Plenty, directed by Fred Schepisi and starring Meryl Streep, followed by his directorial debut Paris By Night (1989), an original thriller that saw Charlotte Rampling play a depressed British politician who gets entangled in a murder case in Paris.

But it wasn’t until serving as screenwriter on the great French filmmaker Louis Malle’s Damage (1992)—a marvellously erotic tale starring Jeremy Irons and Juliette Binoche—that Hare really started to learn the ropes of filmmaking. He recalls the rigorous exercise that Malle would enforce daily in order to peel Hare’s narrative down to its barest bones. “[Malle] would sit there and say, ‘Tell me the story of the movie’” he laughs. “He made me sit there with him every morning for 10 days and I would tell him the story of the movie, until I could do so, word by word, in 40 minutes. This was before I had even written the script. Then he said, ‘Now go away and write it.’ Writing was a formality once I had done all that.”

What followed was an illustrious career juggling both the stage and screen, big and small, with his television movie Wetherby going on to win the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1985.

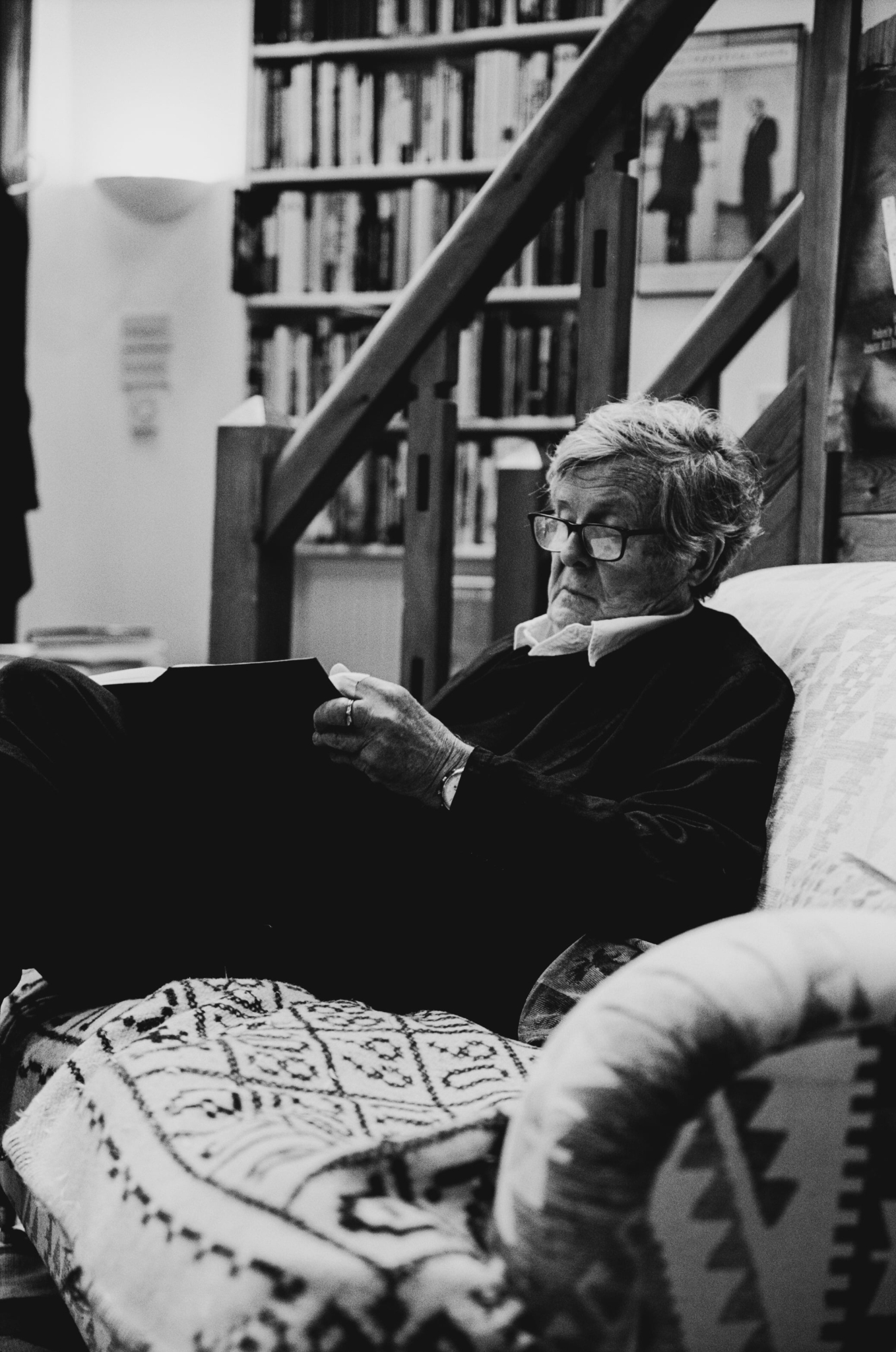

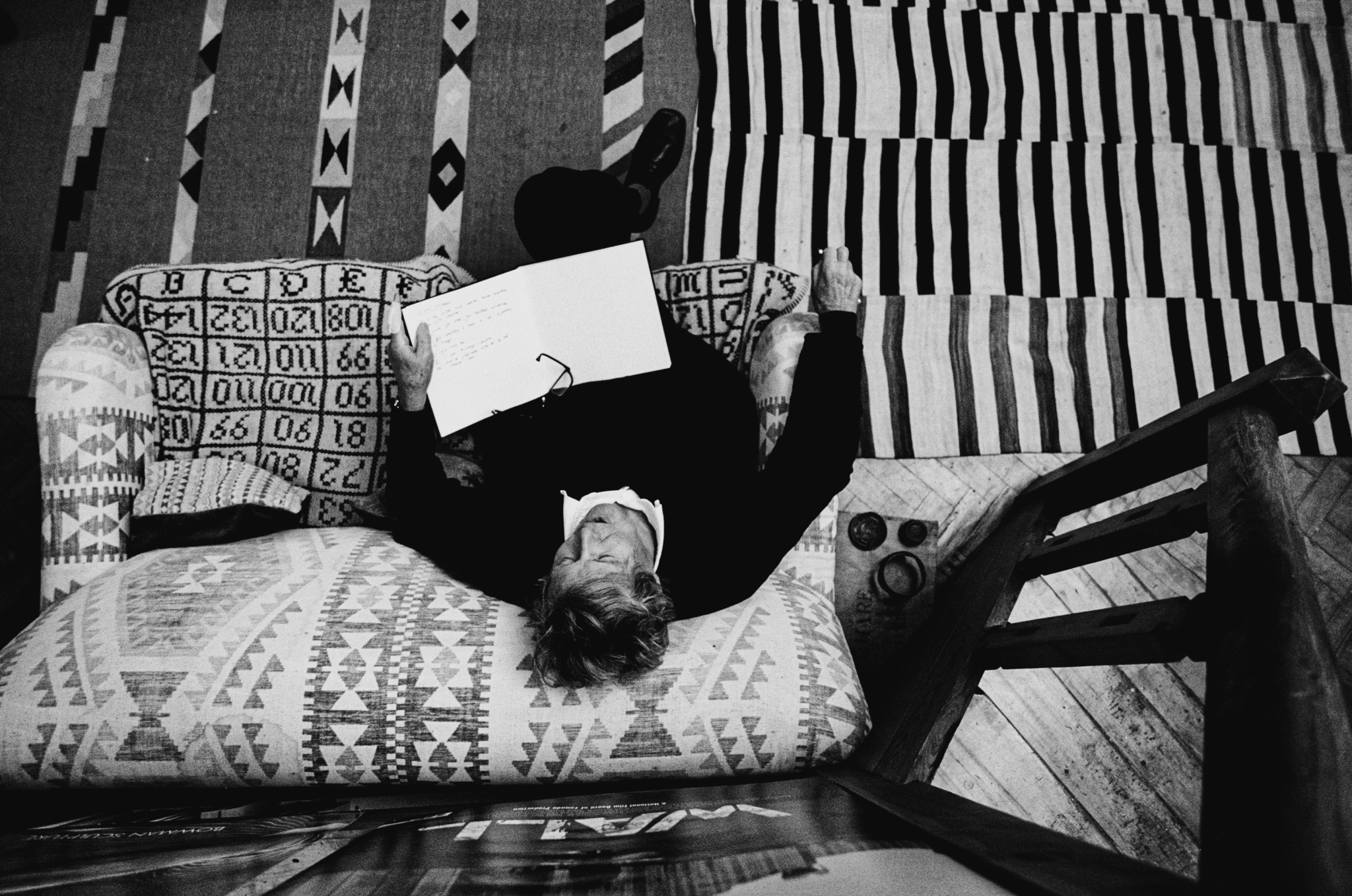

Sir David Hare at home. 2024. By Laurence Hills.

Hare is, refreshingly, as open about his failures as he is about his many successes, especially those regarding his film career. During their conversation, Finch asks him if he considers any of his previous films missteps—does one of Britain’s most accomplished writers have regrets? “Yes,” he replies, frankly. “I knew nothing. I remember the year that Licking Hitler (1978) swept the awards, Stephen Frears had made something that year which was losing all the awards, and he was absolutely furious with me. He said, ‘It’s a fluke, you don’t know anything about filmmaking. Anyone can make a first film, but you’ll find out soon how hard it is. And he was absolutely right. I learned from Malle and Daldry. Now I can make films, but unfortunately I’m physically too old to do it. I don’t know how people do it beyond a certain age.” He takes a beat, before adding, cheekily, “Let alone run the United States of America.”

Notably, a passage from Stephen Daldry’s film The Hours (2002)—penned by Hare and following, in part, Virginia Woolf (Nicole Kidman) as she struggles with depression while writing arguably her greatest novel Mrs Dalloway 1925—knowingly captures the plight of just about anyone who has ever truly wrestled with the daunting power of the word. Spoken by Ed Harris’s sickly and suicidal novelist Richard Brown, it goes:

“I wanted to write about it all. Everything that happens in a moment. The way the flowers looked when you carried them in your arms. This towel. How it smells, how it feels. Its thread. All our feelings. Yours and mine. The history of who we once were. Everything in the world. Everything all mixed up. Like it’s all mixed up right now. and I failed. I failed. No matter what you start with it ends up being so much less.”

Though this particular dialogue is near verbatim to Michael Cunningham’s original novel, it speaks to the Sisyphean task of using the written word to embody, in all its complexity, the beauty, terror, and tragedy of the world. Hare remains one of the few that have managed to do exactly that, time and time again, for over 50 years.

Sitting down with Finch, Hare regales with stories of a decades-long career spent traversing the arts—from almost co-directing the Star Wars movies with George Lucas (“I told him I didn’t see that arrangement working out”) to auditioning a then unknown actor by the name of Mel Gibson for a play in Sydney (“I was very charmed by him. I’d never heard of him”). Laced into the fabric of these tales, though, are acute readings on the state of the industry, with Hare lamenting the brief flickers of true artistic freedom he experienced in the mid-1980s as a filmmaker for Channel 4, alongside the likes of Mike Nichols, Stephen Frears and Christopher Hampton. “They gave us a basic million,” he says. “Nothing more, to make whatever we liked. They needed us to make movies, so the power was with us. It lasted a handful of years.” He also lends his opinion on the dominance of streaming services over modern television and cinema. “Right now, we [writers] are the most abject, servile creatures, who are struggling in vain to please our masters. You can’t please them, because fear has entered the room, and you can’t work when that happens. Now they’re just chasing the next hit, but they don’t have the slightest idea what that looks like.”

Having built an insurmountable legacy as one of Britain’s most cherished artistic voices, the virtuoso tells Finch of his adventures in screenwriting, argues against cinema as a purely visual medium, and explains why the film industry is in dire straits.

Charles Finch: Why did you never make Skylight into a movie?

David Hare: Because it’s set in one room. They’re awful, movies in one room, aren’t they? Liam Neeson and Nicole Kidman wanted to do it, but I said no. And the French are always asking to do it, because they think they can do it better than the English. But I looked at the structure of it, to see if I could make a story of it set outside the room, but I didn’t think I could. I don’t like the idea of anyone else doing my work but me. Perhaps that’s wrong, but it’s also not bad having something that everybody else wants to do, is it? It’s quite nice saying no [laughs].

CF: Great writing on screen is sometimes totally ignored and at other times totally embraced.

DH: Nothing makes me bridle more than seeing the ridiculous cliché that film is a visual medium, because it isn’t. It’s the collision of image and word that makes a movie so powerful. If you think of the most famous moments in the history of the cinema, one is Bernstein in Citizen Kane (1941) saying “I only saw her for one second. She didn’t see me at all, but I’ll bet a month hasn’t gone by since that I haven’t thought of that girl.” You’ll notice that Orson Welles doesn’t flash back to a picture of a woman, because he knows it’s gratuitous, he knows the whole audience can see it because it’s so beautifully described in the dialogue. There are a thousand cinematographers who

can photograph John Travolta beautifully in the Champs-Élysées, but there’s only one human being in the world who could have written a speech for Travolta about what kind of burgers you can get in Europe. And that man is called Quentin Tarantino. That is dialogue you remember for the rest of your life.

CF: I’ve seen directors destroy good movies by thinking they can rewrite the work of great writers.

DH: They think writing is a skill that everybody has. The reductio ad absurdum is when you get asked to rewrite particular scenes in movies. I’ve been asked to rewrite a train scene in a movie. I asked why, to which they said, “Oh, well you’re very good at train scenes”, as if it was a niche speciality. You would never say to Tom Cruise, “You’re going to do 10 reels of this film but the 11th reel is comedy and you’re not really good at comedy, so we’re going to get another actor to do your bit.” If you interchanged actors like they do writers on a movie, you’d never be able to follow the story at all. Yet we are regarded as interchangeable.

CF: Which do you enjoy more: screenwriting or playwriting?

DH: There was a lovely bit on Licking Hitler (1978) which gave me the kind of high adrenaline that you get from filming. There was a crucial scene coming up the next morning, and Kate Nelligan came to me in the evening and said “I don’t think what I’ve got tomorrow is enough, I need something more in this scene.” So you go to bed and you get up at 4am and you write something, and you hand it out to the actors and they say “Oh, this is fantastic, we can do this.” It’s not rewriting in the sense that you’ve been ordered to rewrite. It’s not selfish for an actor to come to you and tell you they need more. It’s the same working with Kate Winslet. If you did a cartoon of me going into Kate Winslet’s caravan at eight every morning, you’d just have a picture of a caravan with BIFF, WHAM, and BOING coming out of it while we argue the text inside. But she’s not fighting out of ego, she’s fighting to make the film as good as it can possibly be. It’s very hard, but both of us found those conversations incredibly fruitful.

CF: Actors have a gut feeling, don’t they?

DH: I love that about actors. I’m not talking about the ego-driven ones, or about the frightened ones. Those are the killers, the ones who fear how it will look. The ones who worry, “What will they think about me?” I’m talking about the wonderful actors, like Carey Mulligan, Kate Winslet, and Kate Nelligan.

I once auditioned a young Mel Gibson for a play I was doing in Sydney in 1980. He wasn’t terribly well known at the time. I put down some lines for him to read, and he burst out laughing. I asked, “Mel, what are you laughing at?” He said, “David, I’ve never said anything longer than ‘pass the salt’” [laughs]. He just stared at the sheets going, you know, “Beats me.” I was very charmed by him. I’d never heard of him.

The collaboration you get on film is fantastically exciting. Unfortunately, it’s hard to get to that point, because to get there is to go through so many stupid people. When I did Denial (2016), I reckon I spent 10 times as long in rooms arguing for my script than I did writing it. Most writers will tell you that’s what it is now. It’s worse in film. In television, they fight over the first episode, they don’t give a damn what you do after that. That’s why most series are bollocks. You watch the tension go out of them because they’ve spent a year fighting about the first episode, then they tell you to go and write the other eight. Most subjects need half that amount.

“Right now, we are the most abject, servile creatures, who are struggling in vain to please our masters.”

Sir David Hare

CF: Do you get offended when executives dislike something that you cherish?

DH: My ego is much more damaged by the audience than it is by the executives. There have been two periods in my lifetime when the balance between the industry and the artist has been in our favour. One was when Jeremy Isaacs founded Channel 4 [in 1985], the policy of which would be that there would be a movie every week. He would come to people like me, Stephen Frears, and Christopher Hampton, and he would ask us to make films so they would have something to show on Thursdays. They gave us a basic million, nothing more, to make whatever we liked. They needed us to make movies, so the power was with us. It lasted a handful of years. I made my first feature film, Wetherby (1985), under those conditions, and it won the Golden Bear at Berlin and brought them a huge amount of prestige. In the middle of the last decade, the streamers needed us more than we needed them, and there was a wonderful moment during the read-through of Collateral (2018) where I asked the people at Netflix whether they had anything to say, and they said, “Yes: love it, love it, love it.” There was tremendous creativity in American and British television at those points, where the artists enjoyed power again. Right now, we are the most abject, servile creatures, who are struggling in vain to please our masters. You can’t please them, because fear has entered the room, and you can’t work when that happens. Now they’re just chasing the next hit, but they don’t have the slightest idea of what that looks like.

CF: Do you feel you still have trust in audiences as a screenwriter?

DH: I believe wholeheartedly in the audience. They’re not always right, because there’s avant-garde work that’s ahead of its time, and I’ve seen enough work that was completely overlooked at the time and is now accepted as classic to know that you can produce work which is ahead of the audience. But do I think it ought to be possible to make films that the public go to see in the cinema and engage with intellectually? Yes. Something is structurally wrong that that is not happening.

When I made The Reader in 2008, they told me that it was the last of the “25-million-dollar art films”, meaning a film whose subject is theoretically niche but which you are pouring a huge amount of money into for production value. Similarly, The Hours (2002) was a 25-million-dollar art film. For God’s sake, it’s about Virginia Woolf killing herself! But we believed we could give it a quality that could reach the public at large. We knew that by using that money to make a film to a certain standard, we would make a profit. And they did indeed make a profit on both those movies. But they no longer believe in that kind of investment. After The Reader, we said, “Well, you probably made about $100m profit on that film”, and they said, “We don’t want to make $100m any more, we want to make $500m.” That kind of thinking is what has destroyed the film industry.

CF: It’s rare to find producers on a mainstream level these days who feel truly passionate about the movie they’re making.

DH: Sydney Pollack was the best note giver I ever had. He read the script for The Reader and he had one note: “In your film, a legal student has an affair with an older woman immediately after the war, and by coincidence, he goes to a trial where she realises she was a concentration camp guard. If the audience doesn’t swallow that moment, your film’s finished.” He knew that the minute the audience ceased to believe, the minute they thought you’re manipulating them, it would come crashing down. In a novel you can use style and good writing to cover up implausibility, but in film you can’t do that, because the audience is constantly asking themselves, “Do I believe this?” He said, “If I were you, I would work on that moment.” And we did, tirelessly.

CF: Were there a whole new set of rules you had to learn when you were screenwriting for the first time?

DH: I didn’t begin to learn about screenwriting until I worked with Louis Malle on Damage (1991). He would sit there and say, “Tell me the story of the movie.” He made me sit there with him every morning for 10 days and I would tell him the story of the movie, until I could do so, word by word, in 40 minutes. This was before I had even written the script. Then he said, “Now go away and write it.” Writing was a formality once I had done all that. We had already solved all the problems, just by reducing the story to its narrative. Once I learned that technique, a lot of things became easier.

Sir David Hare at home. 2024. By Laurence Hills.

CF: How quickly can you discern in a meeting with a director that you don’t know whether or not they understand the essence of the material that you’ve written?

DH: The question I ask myself instead is: is this director a collaborator, or do they believe they are a genius? You can tell who the big-headed people are. I won’t name names but somebody once asked me to write a Bond film and the minute I went to meet that director I knew that it would be a waste of time working with that person. If a director isn’t prepared to sometimes yield to other people’s talent, they’re just idiots, aren’t they?

CF: What’s the craziest thing you’ve been asked to write?

DH: I was asked to write the fourth and fifth Star Wars films. I was asked to co-direct them with George [Lucas], because he told me that he wasn’t very good with actors and he had heard I was. He asked if I wanted to direct the actors while he directed the shots. I told him I didn’t see that arrangement working out. The most offensive was when I was asked to remake Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949).

CF: Are there any films you consider missteps?

DH: Yes. I knew nothing. I remember the year that Licking Hitler won all the awards, Stephen Frears had made something that year which was losing, and he was furious with me. He said, “It’s a fluke, you don’t know anything about filmmaking. Anyone can make a first film, but you’ll find out soon how hard it is.” And he was absolutely right. I learned from Malle and [Stephen] Daldry. Now I can make films but unfortunately I’m physically too old to do it. I don’t know how people do it beyond a certain age, let alone run the United States of America.

CF: Sometimes they don’t do it particularly well after a certain point.

DH: Robert Altman used to sit on a high stool in the middle of a set and people would come to him. Then again, he always had a casual approach to directing. Altman once said to me “You’re a screenwriter?” I said yes, and he said, “You know what I do with a screenplay? I tear it up on the first day.” He rings me a week later and says, “I’ve got a great subject I’d like you to write—I want to make a film about Mata Hari.” I said, “Bob, you’ve just told me you tear the script up on the first day.” He said, “Oh, yes, but I wouldn’t do that if it was you.” [Laughs].

Sir David Hare at home. 2024. By Laurence Hills.

Footnote

The following dialogue, from 1995’s Skylight, is an especially resonant passage from Hare’s oeuvre: “You give them an environment where they feel they can grow. But also make bloody sure you challenge them. You make sure they realise learning is hard. Because if you don’t… then what are you creating?”