Art & Photography, Confessions

The renowned Dutch photographer discusses his long career which has seen collaborations and portraits with the likes of Kraftwerk, Depeche Mode and Courtney Love.

Anton Corbijn — Dutch photographer, filmmaker, and art director—has a distinct career which has spanned nearly five decades. Favourite Darkness, his current show at Kunstforum in Vienna, is named after a line in a track (‘In Your Room’) by Depeche Mode (a band Corbijn has worked with to shape their visual direction since 1981), and casts light on over 200 works, arranged in eight chapters.

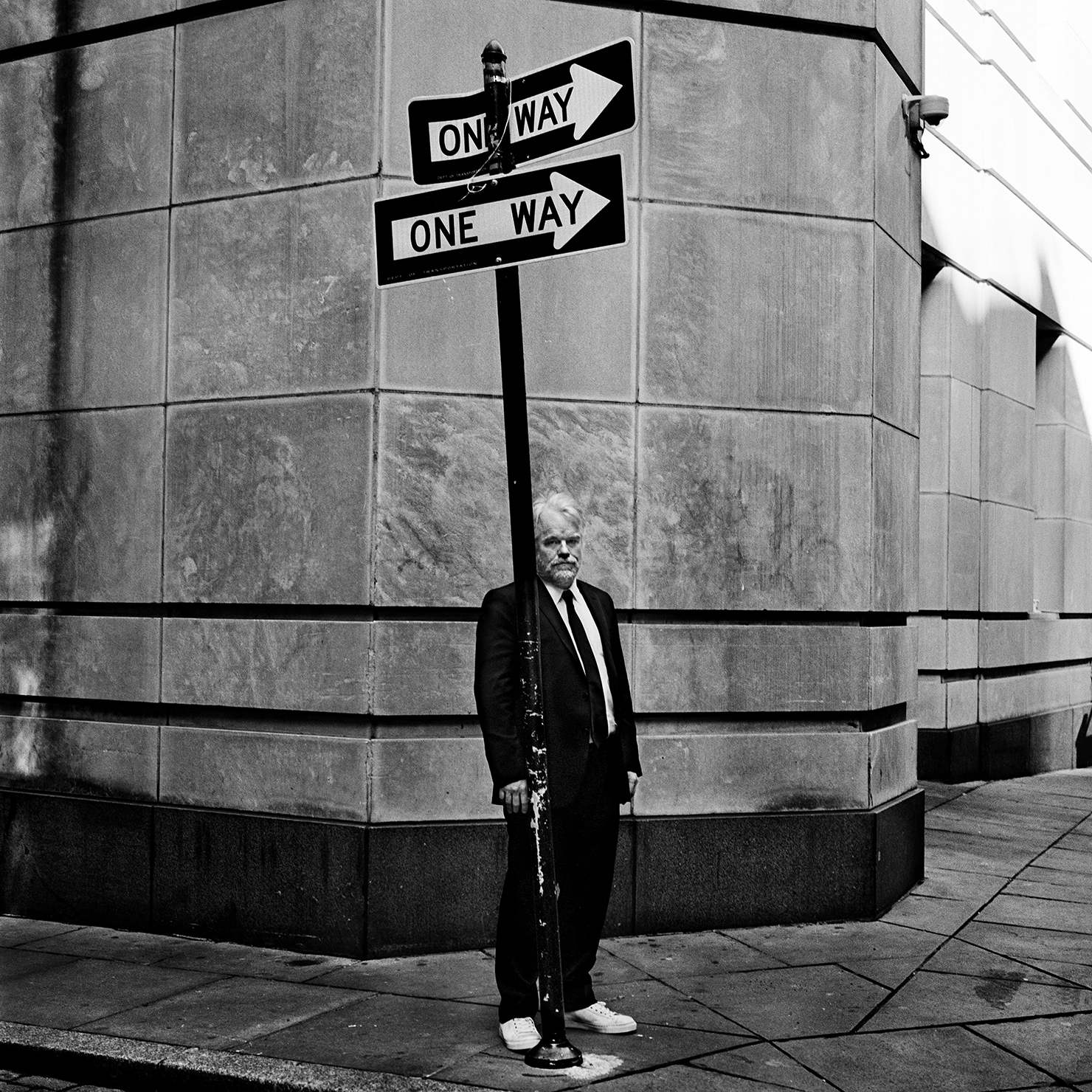

Running in parallel to Favourite Darkness at Kunstforum, a further glimpse into Corbijn’s multifaceted oeuvre—spanning the last 50 years—has just opened at Fotografiska Stockholm, running from June 13 through October 12. There, as with Favourite Darkness’ extensive accompanying catalogue, Hannibal Publishers present a further volume featuring Corbijn’s staple photographs as well as never-before-seen images. From Swedish artists such as Sophie Zelmani and Neneh Cherry to global icons like The Rolling Stones and Johnny Cash, Corbijn’s carefully co-curated exhibitions emphasise both retrospection and range—proving once again that he is far more than just an image-maker of iconic figures, but a quietly radical artist of nuance, depth, and enduring vision.

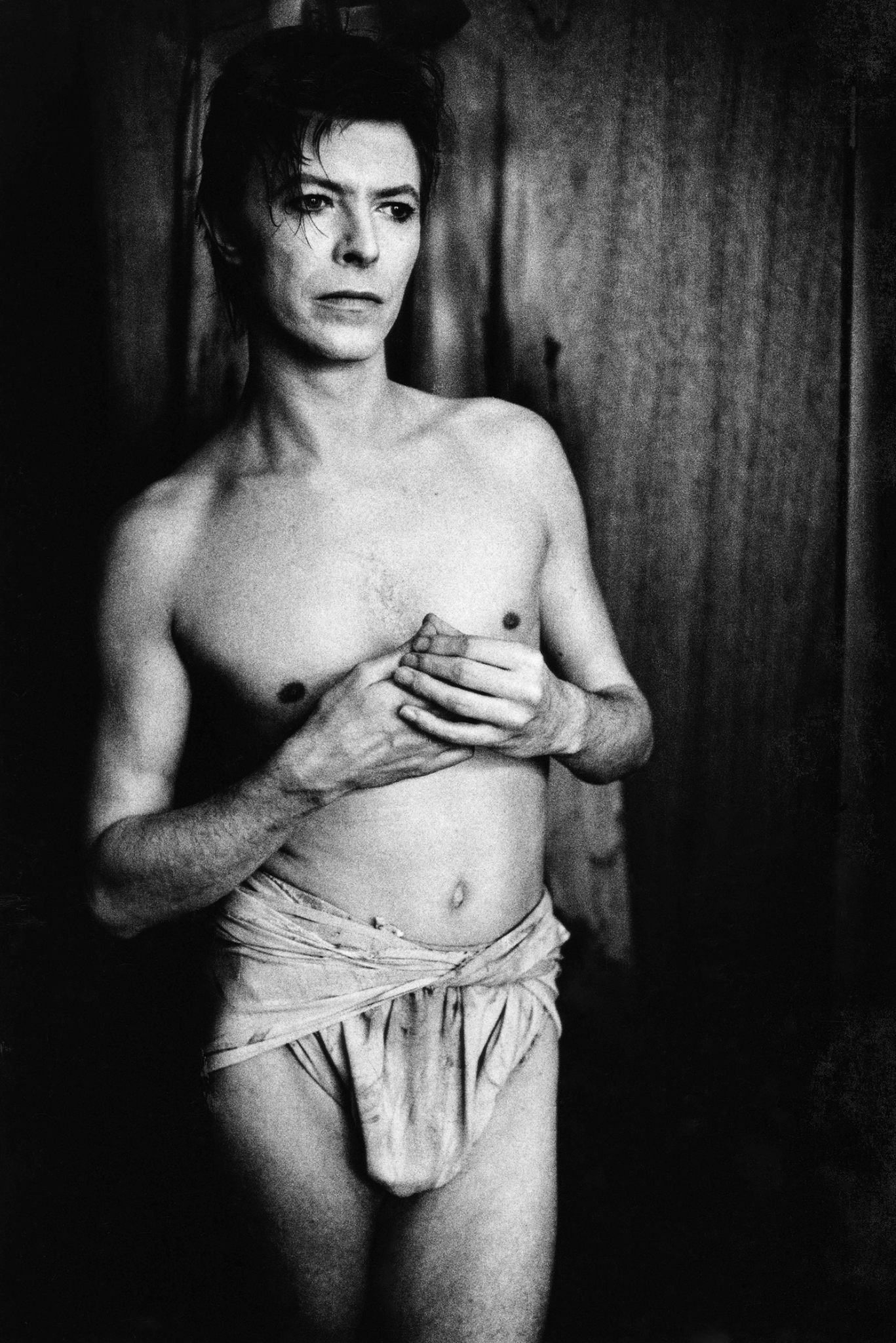

A popular modernist, Corbijn has long stood at the forefront of visual culture. Veering away from the exhausted “rockstar photographer” narrative, the exhibition presents his expansive oeuvre, beginning with gems such as a portrait of Nelson Mandela, artists from an intellectual disabilities workshop, and a collaboration with feminist painter Marlene Dumas. It also includes his pivotal beginnings at Dutch music publication OOR during the mid 70’s, to a trailblazing five-year tenure at New Musical Express (now NME) from 1979. We see stripped-back portraits of David Bowie, Miles Davis, Joy Division, and Kraftwerk, alongside archives including original covers.

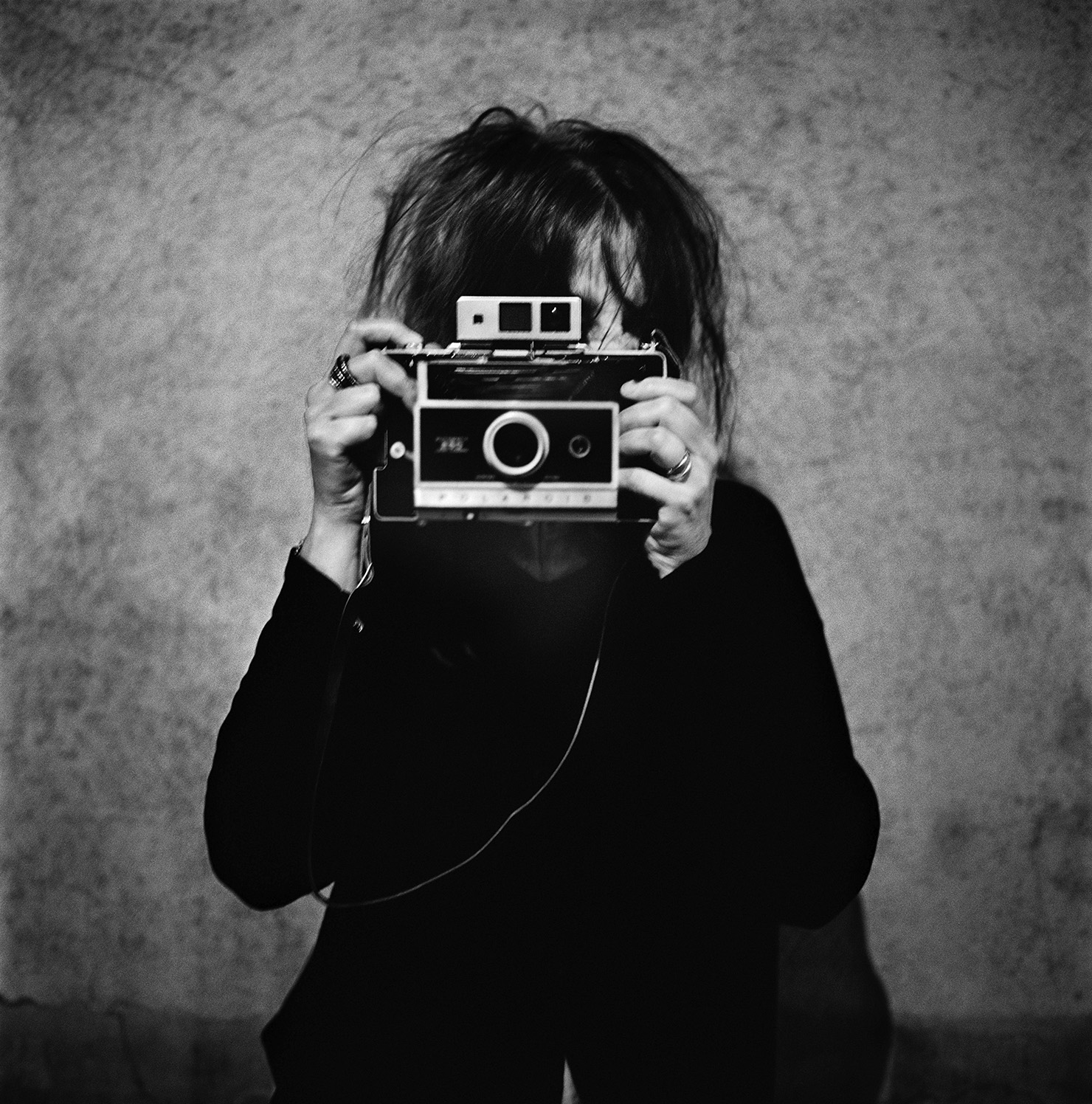

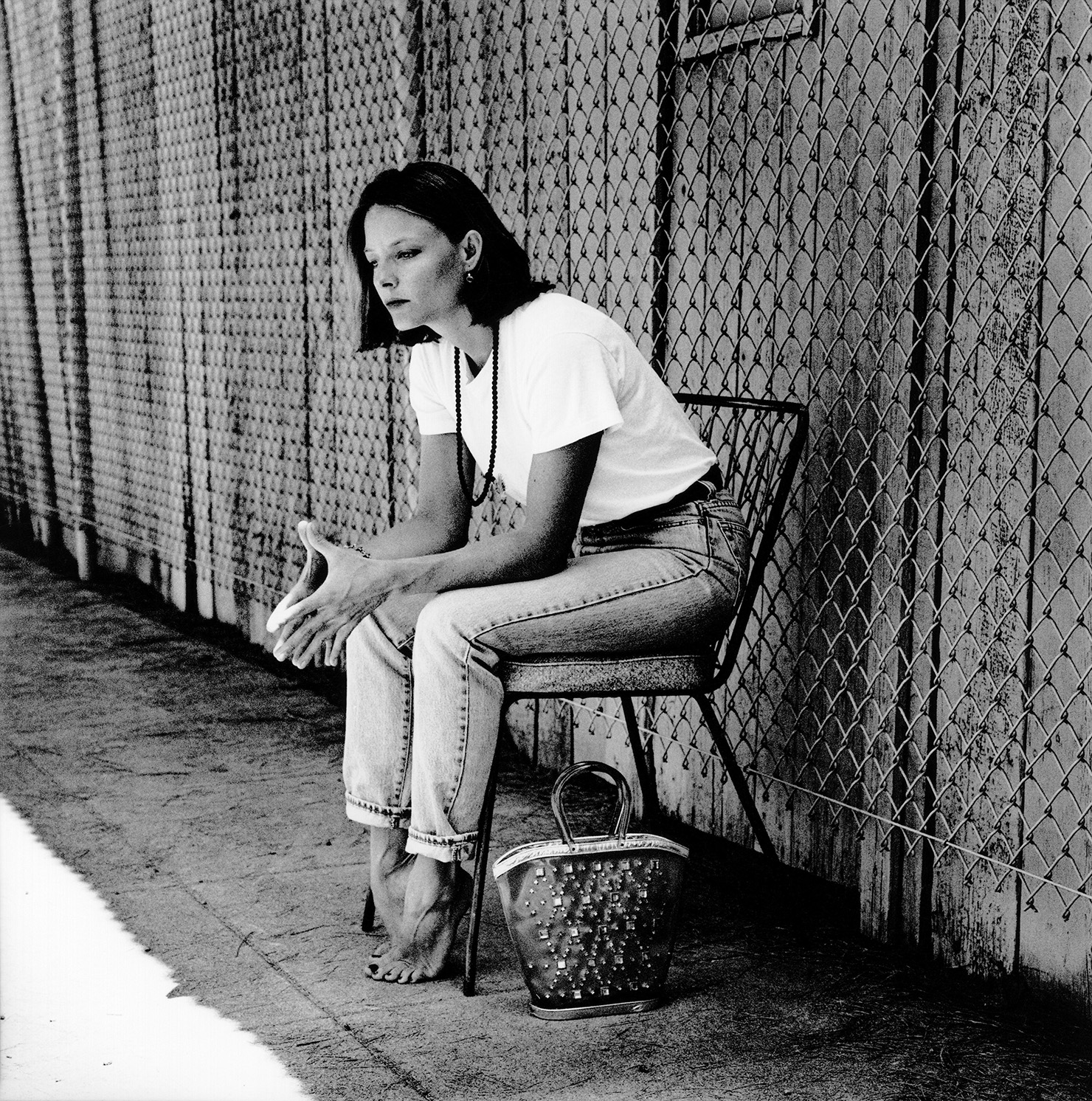

The central hall delves into Corbijn’s fascination with religious iconography and art history. A rare series shot in Catholic cemeteries in the early 1980’s captures angels, saints, and mourners in high-contrast, intimate compositions. Anachronistic tableaux shot between 1983 to 2013 appear: Courtney Love as Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, Mick Jagger and Bryan Ferry masked as devils—all testaments to Corbijn’s stark, visual mastery.From seminal music videos (Joy Division’s Atmosphere, Nirvana’s Heart-Shaped Box, Arcade Fire’s Reflektor) to his decades-long role as Depeche Mode’s art director, the final rooms trace Corbijn’s work from the 1980s onward. Highlights include a section dedicated to women featuring Patti Smith and Kate Bush; and a closing section of artists’ studio portraits, including Lucian Freud, Ed Ruscha, and Kiki Smith.

A Rabbit’s Foot sat down with Anton Corbijn on the occasion of his 70th birthday in May to revisit the grit and grace of his vision, working with musicians and his career as a director.

Sayori Radda: What would you identify as the exhibition’s focus?

Anton Corbijn: The rooms include a dedication to women, a section on artists, or religious iconography. Sometimes religious connotations creep in without me aiming for it. As the son of a protestant minister, this subject is not far removed from my personal background.

SR: Let’s discuss the introductory room “My World”. Why did you choose to open the exhibition with lesser-known, unconventional subjects?

AC: Iconic images are what people already know—quite a few of them come up later in the exhibition anyway. I wanted to show work that people aren’t aware of. Often I am described as a rock photographer, yet I don’t think I am. I love music, so I shot a lot of musicians 50 years back. This room displays a self-portrait of mine, or presents a work depicting artists with intellectual disabilities taken at De Heygraeff, an artistic workshop in a sheltered residential care park in Zeist. It’s wonderful to see people with an outlet—you can understand them better through seeing what they’re making.

SR: Tell us about the second room, which explores your career beginnings…

AC: These are early photographs—I had shown NME portraits I took for Dutch magazine OOR of Elvis Costello, John Martyn and Johnny Rotten—NME loved them and that’s how my career began.

SR: Were you deliberately challenging how musicians were conventionally photographed?

AC: Not consciously. People would say “oh that’s your style”, but I couldn’t photograph in any other way, so that then becomes your style – your inability to do differently. I generally didn’t like to photograph musicians with their instruments or in a backstage setting.

SR: Women were largely sidelined in the male-dominated music scene. You photographed artists like The Slits and Siouxsie Sioux. In the case of Nina Hagen and Ari Up — why choose that portrait as the main visual for the exhibition?

AC: I didn’t want an overused work like say, Miles Davis… I wanted something else. Do you think it was a little on the edge?

SR: Not at all. I see it as a counter-narrative to the male-dominated visual history of music. They were subversive, avant-garde… against the grain.

AC: Exactly. Looking back at all the music we had access to, most of them were men. Women weren’t in the limelight, unfortunately.

SR: What drew you to religious iconography early on?

AC: I grew up as a protestant in the small Dutch village of Strijen. There was no iconography in that sense, just crosses. I was born next to a cemetery; from our garden you could see my father’s church—he was a pastor. Later, we moved to a far more Catholic place, which sparked my interest. There seemed to be more of a celebration of life, everything can be forgiven. Before, it was a strict protestant upbringing; no fun.

SR: Did growing up in Christian faith shape your image-making?

AC: Not consciously. When I look at Arcade Fire resembling The Last Supper, it’s undeniable. Early on, I was drawn to cemeteries; I felt like they had depth. When I was young, I printed my photographs extremely dark, as I wanted to bring this across. I’m unsure whether the darkness within religion was conscious to me when I was young. I didn’t want to be a part of it. But if it’s been with you your whole life, it likely influences how you take a photograph.

SR: Did music allow for an escape?

AC: Yeah, when I was 11 we moved to the center of Holland—that was great for me. I started going to the record store. Previously, I had only heard music at the hairdressers where I was introduced to the Beatles, and I thought to myself, “God, there’s this whole world outside of this island.” I always called it the promised land; the other side of the water. When I found the camera at 17, music was the most logical subject for me to photograph; it’s all I was interested in.

SR: You often use masks, dolls, props that obscure faces. Why these motifs, as seen in Kraftwerk, for example?

AC: It’s playful; the masking is more about building myth than capturing reality, like a small act of visual theatre. The portraits of Kraftwerk weren’t a grand plan. I took photographs of them at a concert in Barcelona. After the show, I walked across the stage and I saw these dolls standing there, so I took a picture, one of each, and that was it! Years later, I thought “they look great together!” If I had planned that I would have taken a series. These dolls symbolised Kraftwerk. I incorporate people and manifestations of them, to symbolise their music. Like NME’s known cover of Joy Division, where the band descends into unknown pleasures, the title of their album at the time. In England they were always looking at what kind of clothing people were wearing–rocker, mod, punk or whatever. In Holland this wasn’t a big deal, I didn’t look for clothes, rather at the atmosphere.

SR: How did photography inform your move into music videos, and subsequently filmmaking?

AC: My photography influenced my videos as the initial music videos were still shot images arranged image for image, rather than a moving camera or a cinematic experience. In 1986 I made my first video for Depeche Mode; and there was no budget for a camera director. I taught myself—hereafter it became moving. Vice-versa, my photography became easier whilst shooting; less controlled, more intuitive.

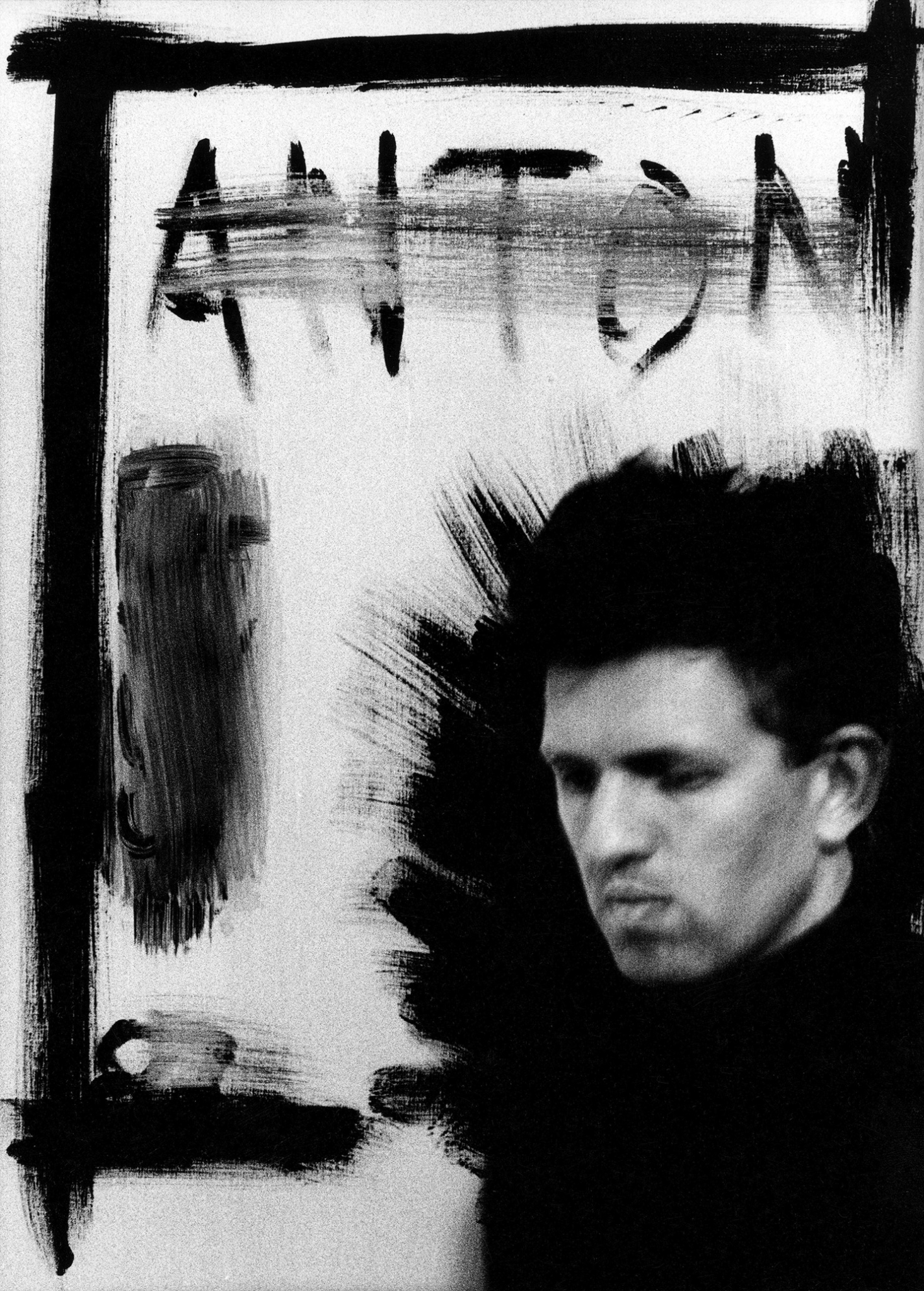

Self Portrait, London 1987 © Anton Corbijn

In 1986 I made my first video for Depeche Mode; and there was no budget for a camera director. I taught myself—hereafter it became moving. Vice-versa, my photography became easier whilst shooting; less controlled, more intuitive.

Anton Corbijn

SR: This brings me onto Control, the 2007 black-and-white biopic about Joy Division’s Ian Curtis—your directorial debut that extended your stark photographic style into film, including beautiful, long, still shots that add to the silence, and heavy yet sincere atmosphere of the film…

AC: Thank you, that was very deliberate—to create something where you hold still and just observe. For every film script I received, they would add “you should be making films because your videos are like little films.” My music videos were rich in narrative. But I was shy and couldn’t see myself being the head of 150 people, so I always turned opportunities down. With Ian, I had met him and was emotionally attached—if I ever made a film, this would be the one.

SR: How was the intimate mood shaped through techniques? The music in the film was actually performed live…

AC: The Joy Division songs were surprisingly simple in composition. The actors learned them. I didn’t suggest it, but they were keen. Sam Riley, the actor playing Ian Curtis, was in a band, so he could sing. It was fantastic—I would record what they played a few times until we got it right. It wasn’t produced by a studio, so I had a lot of say.

SR: The Reflektor music video you directed for Arcade Fire in 2013 echoes many of the themes throughout your practice— ritual, anonymity, and mirrored selves…

AC: It happened naturally. The themes you mention were unspoken. My approach often carries a deeper meaning than the way I direct. The result tends to feel more meaningful—not because of what I tell them, but because of how I capture it, or what they end up doing. I automatically veer towards masks; they had them on set already. I get asked to do things by people who already like and know my work, so it’s quite organic. Additionally, this music video was the biggest budget I ever had. David Bowie, who sings the background vocals, couldn’t make the trip —he was already sick. Instead, without prior knowledge, he sent his mask onto our set. Win Butler was friends with Bowie. At first I was disappointed, yet when I saw the mask I thought— that’s amazing!

SR: What about the shot you took of this death mask – it’s so immediate and haunting!

AC: Out of excitement, I snapped it, untouched; the second I opened the crate.

SR: There’s a section dedicated to your well-known collaboration as Depeche Mode’s art director…

AC: I didn’t like their music at first, it was too pop. Now I think they’re great. It started with a music video in America in 1986, then it became stills, album sleeves, stage design – all-encompassing really. They trusted me, their music changed… it worked well with my visuals.

SR: Tell me about your collaboration with the feminist painter Marlene Dúmas.

AC: Marlene had always painted from found clippings—newspapers, magazines, photographs. We decided to flip that, and create original material. The idea was to photograph women strippers at clubs in Amsterdam, and have her paint from them. That way it was a new process for both of us. Marlene often works with nudity; I hadn’t. Honestly, I was a little shy about it, but the experience of photographing someone nude felt less intimidating with Marlene around.

SR: With Cannes Film Festival having wrapped up, we’re reminded of Control, which screened there in 2007, receiving both the Label Europa Cinemas Award and a Caméra d’Or Special Mention.

AC: I should have won the Caméra d’Or. They awarded the prize to another film they felt needed more recognition; assuming, because I was a known name, that my film was well-funded. In reality, I had to sell my house. Afterwards, they said mine was the better film, and had they known the circumstances, they would have given it to me. I don’t make films for awards, but they do help with sales.

SR: Could you share anything about your upcoming feature film?

AC: It’ll likely be called Switzerland; a fictional story set in 1995 Switzerland, where Patricia Highsmith lived and died. It follows her final years, and is based on a 2014 play by Joanna Murray-Smith, who wrote the screenplay. Highsmith, played by Helen Mirren, has cancer, and her publisher sends a young editor, played by Alden Ehrenreich, to convince her to write one last Ripley novel. They collaborate, but things take a dark turn. We’re seven weeks into editing, with the director’s cut coming up soon. Hopefully it’ll be ready for Venice. We can’t wait.

Corbijn, Anton is on at Fotografiska Stockholm until 12 October and at Kunstforum Wien until 29 June.