As a new show arrives in London, Kitty Grady meets the artist Suzy Murphy at her Chelsea Studio to talk about being inspired by William Blake, epiphanic moments and the emotion of the natural world.

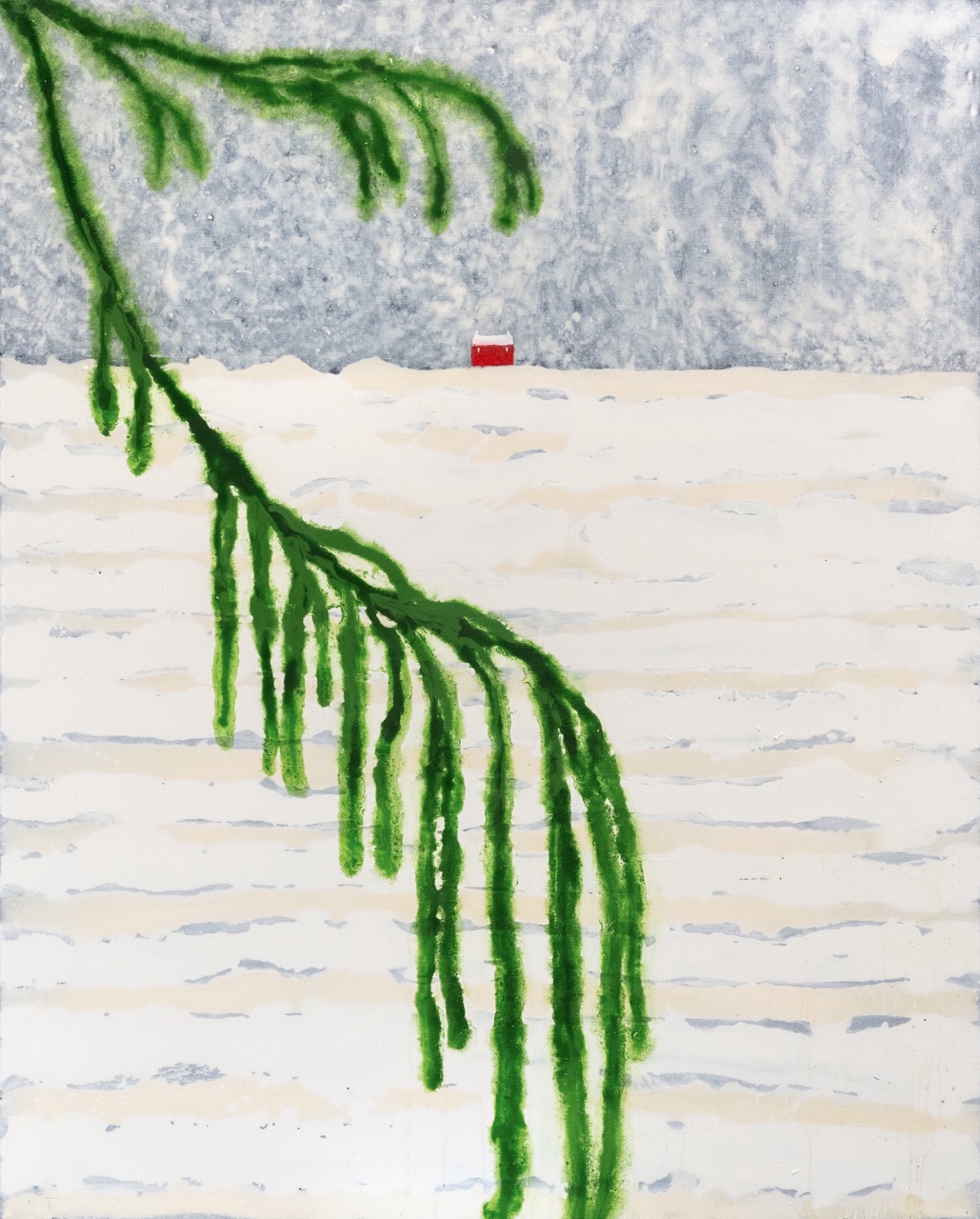

Distant Deeps or Skies, the latest exhibition from painter Suzy Murphy, features a recurring motif of a small house, dwarfed in the canvas by immense, celestial skies. A beacon of safety amongst the vastness of the universe, the image comes to mind when I meet Murphy on a dark, rainy afternoon in late November. At the doorway of the white 1920s building her Chelsea studio is located in, the artist greets me with a warm hug and leads me inside where a fire is blazing.

Murphy started working on the paintings—which, created with oil paints, also include details of flourishing blossoms, clouds, rolling hills and the moon—whilst on a residency in Hampshire last year, but the key influence in the paintings stems from elsewhere. “The whole show has been painted around the idea of William Blake and his poetry,” says Murphy, handing me a coffee and a plate of dates as we take a seat by the fire amongst piles of books and paint palettes. “I’ve based the show around his Songs of Innocence and Experience. I love how you can get as much as you want from every poem, they can be seen as just a beautiful, light ditty. Or you can see such depth.”

The same can be said of Murphy’s canvases, which, each named after a line from Blake, are naif in style and lean on simple forms, whilst containing multitudes within. “You can see them as a pretty picture, or you can look more deeply and see that my blossoms mean regeneration and rebirth; they are symbolic of spirituality,” says Murphy. “Blake had this idea that Jerusalem was England, but it could also be this place within us.”

Suzy Murphy, To Welcome The Spring, 2025, Oil on linen. Courtesy of the artist and Lyndsey Ingram.

Murphy calls her paintings as “emotional landscapes”. “I never see myself as a landscape artist because for me they are all self-portraits. I use the landscape to express how I feel. I try not to think of them as canvases, I think of them as pages,” explains Murphy, who reads aloud to me from her diary, where she maps out thoughts that then inform her work. “The ‘experience’ paintings were definitely easier,” she adds. “I’m closer to experience than I am to innocence. I really had to dig deep to remember the innocence.”

Murphy was born in 1964 in Whitechapel, London, and brought up in a large, multigenerational Irish family in which 10 people lived in one council flat. Aged 5, Murphy’s stepfather and mother, who was 18 when she had her, moved from London to Alberta. “I was uprooted from the East End, kicking and screaming inside,” she says. “I longed to be back in Whitechapel with my grandparents and my mum’s siblings who were like my siblings.” In Canada, Murphy, unable to express her feelings of dislocation aloud, found relief in the landscape. “I remember running through the prairies, I remember the freedom. Somehow that became comforting to me—these vast open spaces. This longing and sadness in me was comforted by the land, which you’re tiny in.”

Aged 7, Murphy moved back to London, to the East End, before her mother and stepfather took on a sweet shop in Clapham they also lived above. Art came into the picture when, killing time with her cousin Sheenagh, they got the bus to Traflgar Square from Whitechapel and stepped inside National Gallery. “I just walked in because it was free,” she recalls. “It just really moved me as a child.” Wanting more for her daughter, Murphy’s mother sent her to a nearby private school, James Allen’s Girls school, where her artistic skill was identified and she ended up doing a foundation year at St Martin’s. “That journey set me free,” says Murphy.

Murphy recalls a “lazy” A Level History of Art teacher, who rather than give her lessons, would tell her to go to the Tate Britain. Doing a project on the progression of female portraiture in the museum (“way ahead of my time,” jokes Murphy), she discovered the Blake Room. Murphy pulls out a slim pamphlet of his poetry she bought at the gift shop bought with pocket money. She took it upon herself to learn poems by heart.

“Lines would go around my head for the rest of my life,” says Murphy, who describes a particular line that perplexed her: “And we are put on earth a little space, that we may learn to bear the beams of love,” Blake writes, in ‘The Little Black Boy’. “I used to think what does that mean? What does that mean? And then one day, in my late 20s, I was in Hyde Park, walking around the Serpentine, and I remember thinking, oh I get it. It’s so hard to accept love.”

As Murphy talks to me, I notice her creative life is filled with such epiphanic moments. Whilst on a recent trip to the V&A Museum of Childhood (Bethnal Green Museum) she had a flashback of how, as a child she would go there to see the dolls houses after pie and mash and trips to Woolworths to buy colouring pencils with her family. “I was like, God, this is where my little house comes from.”

“I think art saved me many times, it really did.”

Suzy Murphy

The symbols in Murphy’s work are deeply embedded. In her larger body of work they include a pet she owned as a child. (“It was a girl dog, but I named her Toby,” she notes of the series, named ‘Toby was a girl’). A second show Murphy is exhibiting in Aspen in February features a series of teepees. “Something I experienced as a child in Alberta,” says Murphy. “Most artists are dealing with their childhood again and again,” she says. “My motivation comes from wanting to make sense of being here. It always did. I think art saved me many times, it really did. Art has been my best teacher and my best friend. If I feel discombobulated, if I feel sad, if I feel anxious, it’s the place that is going to soothe me.”

Murphy calls the experience of preparing two shows this year simultaneously as “schizophrenic.” Yet for the artist, who lives nearby with her family, a constant has been her studio, which also contains a little kitchen, and a mezzanine level with a bed. In the most intense periods of work, Murphy, who also dons a simple work uniform of dungarees, a black t-shirt and her hair always tied up in a bun, stays here during the week, living a monastic life of work and contemplation (although I am surprised to hear she listens to The Clash and Tupac while working, as well as BBC Radio 3). “I’ll be here for five days and see no one. But I never feel alone, I always feel very connected,” she says, describing a trance-like state she can reach. “I never remember how I painted painting when I get there.”

Beyond Blake, Murphy cites inspirations as Rembrandt, Louise Bourgeois, David Hockney “for constantly reinventing himself” and Tracey Emin, “for documenting what it is to be a woman.” A mother of three sons, Murphy—who has also experimented in creating jewellery and ceramics—describes only fully working out what she wanted to say as an artist “much later” in her 40s. Now, she feels a sense of peace in her creative process, even if it still has its challenges. “At this age, I’m so used to things not working. But I just know you push through,” she says, describing the mysterious alchemy of paint. “It’s a bit like playing chess with the universe. Everyday you make one move, it makes one move back. Then slowly the image comes to a resolution inside and outside yourself.”

Distant Deeps or Skies is on at Lyndsey Ingram until 23rd December. Murphy’s show with Galerie Maximillian will open in Aspen on 14th February 26.