The legendary painter and photographer Richard Prince has spent a lifetime documenting the iconography of the West and the American Spirit. Exclusively for this issue, Prince personally hand-picked a selection of images to sit beside an earlier essay he had written that explores how art and the American West came together. He describes his love for cowboy films, his journey through the Times-Life years, and his experiences shooting the iconic Marlboro advertising campaign.

1980-84 is how I date my first cowboy photographs. I showed them at Baskerville & Watson in 1984, on 57th St. NYC, and when they asked me to date them I wasn’t sure when I had actually taken each photograph. All I knew was that I had been making collages with them around 1976, then started to re-photograph them in 1980. I just found a few of these ‘76 cowboy collages in grey folders next to cigarette ads from Camel. Camel back then promoted their campaign based on a “safari” concept. In 1976, the cowboys and the Camel ads were simply torn out of magazines and the text was covered with masking tape and the page was pasted to 8X10” blank pieces of paper. That’s as far as it went. Like a lot of other artists… a traditional collage. In 1977, I started to “re-photograph”… but not the cowboys. My eye was drawn to advertisements of watches, perfumes, pens, dressed-up men and women looking like sculptures. Images that I thought were impossible to believe. Images that I thought had nothing to do with art.

I wasn’t paying attention to my “cowboy” series until around ‘83 when I realised I had taken around twelve photographs of cowboys over the previous three years. I can’t remember how many I showed at Baskerville & Watson, but I delivered maybe fifteen, starting with an 8X10” which could have been the first one I took, and the rest were either 20X24” or 30X45”. The 30X45” ones were the biggest photographs that could be made at the commercial lab. It was a big photograph. The commercial lab they were made in was called Ultimate Image, on Park Ave South, seventh floor. It was the cheapest place in the city to print colour photographs. It was also messy, disorganised and run by a scatterbrain named Aaron Klein, who knew zilch about art and who advertised his business with fireplace pictures of his kids.

I would drop my colour slides, give Klein the dimensions I wanted, and come back in a couple of days to proof the print. Baskerville & Watson didn’t sell any of the photographs that I showed in 1984.

In 1986, when I was camping out in the back of 303 Gallery, Christopher Wool bought my first cowboy photograph. Being real? I didn’t care about being real. Looking real was what mattered, counted, “carried the weight.”

Back in 1982, I was working at Time-Life in a department called “copy process”. It was dead-end boring work. I worked one day a week, a graveyard shift, 6pm to 6am. I would get a 2 hours supper break around midnight.

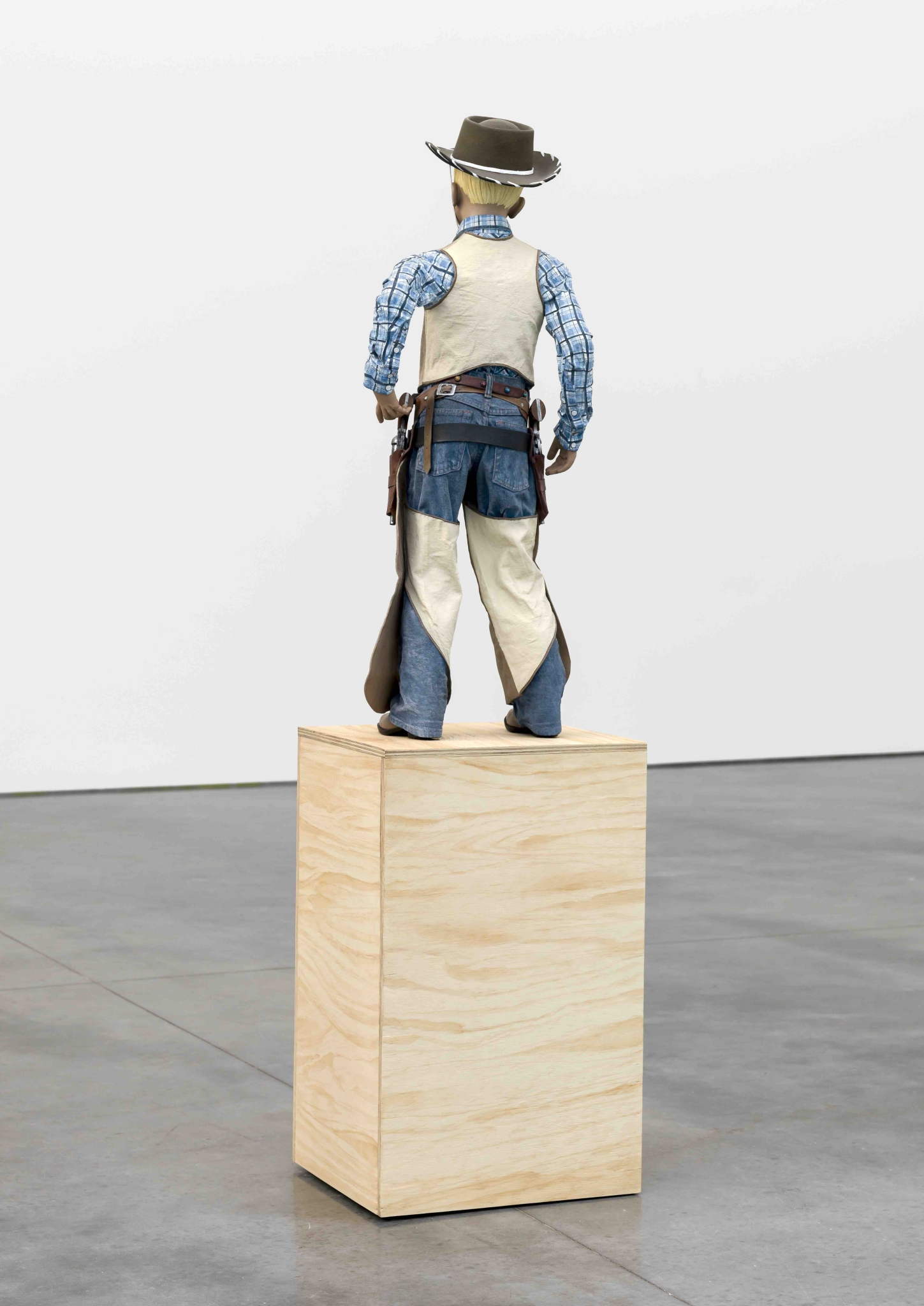

Untitled (Cowboy), 1989.

I can still watch Clint Eastwood in Unforgiven once a year. I can recite the whole last scene, after Clint comes to his senses and walks into the saloon and asks, ‘Who’s this asshole who owns this shithole?’

Richard Prince

Mondays were when the magazines that Time-Life published came out. Time, People, Sports Illustrated, Fortune. There were always stacks of new mags lying around. It was good to get them for free. Fringe benefit. I was tearing out all kinds of ads from the magazines. I’d been tearing since 1977, avoiding the editorial parts of the magazine, only interested in the psychologically hopped-up, art-directed, “creative” pages…the pages that looked to me like some kind of cross between Rod Serling and Groucho Marx. Unlike the editorial parts, the ads didn’t have an author and seemed to suggest something I could believe in. I was struggling in those days with identity, truth, and anger, and the ads provided an alternative reality. Something comforting and exciting and close to what a movie experience does when the lights go down and a story is told. Who cares if Newport Lights was putting on a stupid made up show. I wanted a show. I wanted entertainment. The truth? I wasn’t familiar with the truth. Why would I have been? No one ever told it.

I always liked cowboys on the screen. Big or small. TV or movies. In TV it was Paladin Gunsmoke, (Amanda Blake), The Rifle Man, The Lone Ranger, Zorro. My favorite cowboy movies were Shane, High Noon, 3:10 To Yuma, Rio Bravo, The Professionals, Johnny Guitar, and The Wild Bunch.

The Outlaw, with Jane Russell as Rio, wasn’t a favorite…but femme fatale Jane’s atomic bosom was a world wonder and seduced me into an early fixation on cleavage.

I can remember seeing How The West Was Won in Cinerama at a Boston theater when the “fad” of “Cinerama” had just come out. I was like, ten? I even loved western comedies. The Paleface with Bob Hope. Go West with the Marx Brothers. I can still watch Clint Eastwood in Unforgiven once a year. I can recite the whole last scene, after Clint comes to his senses and walks into the saloon and asks, “Who’s the asshole who owns this shithole?”

The Gunfighter is probably my next favorite. With Gregory Peck. The story about an aging sharpshooter…an outlaw, “the fastest gun west of the Mississippi.” How he has to keep proving his skill when confronted with some young up-and-comer, a “whippersnapper” and how he tries and talks some sense into the greenhorn and can’t and then, even though he doesn’t want to… has to “show him down.” How a star-struck kid doesn’t stand a chance and how the constant battle with fresh showdowns finally gets to him and how, in the end, he has to let his “reputation” go. Let an untested rookie “gunslinger” get his day in the sun. He just gives some kid a head start, a split second, and lets the kid shoot him. Hands over the mantle, the keys to the kingdom. As he lies there dying in the street, Gregory Peck, (Jimmy Ringo) looks up at the kid and says “You won kid. Good luck. You’re gonna need it.” It reminds me of that John Lennon song when Lennon sings about the wheels turning ‘round and ’round. “I just had to let it go.”

Self Portrait, Richard Prince 1973.

I used The Gunfighter’s ending in a letter to Andy Warhol. I penciled the letter on a “white painting” in 1992. The painting is called Peanuts. It’s a big painting. You have to go up close to the painting to read it. It’s handwritten. Part of the letter says: “Andy Warhol was an asshole and so were all his dick head friends and I’m glad he died.” Peanuts is in the permanent collection of the Whitney.

In regards to the Question Painting: Don’t Fence Me In was written by Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, Joe Walsh, Ed Lauter. Warren Oates. Emmet Walsh. Timothy Carey. Brion James. Maury Chaykin. Yaphet Kotto. Ben Johnson. Luke Askew. L.Q. Jones. Jack Elam (the cross-eyed one). You know if any of these “character actors” showed up, it would be a good shoot ‘em up. Dub Taylor. Noah Beery Jr. Warren Stevens. John Dierkes showed up in Shane and One Eyed Jacks. “Jacks,” directed by Marlon Brando…one of the only westerns to actually have a beach figure into the plot. Karl Malden was the lawman in “Jack”…whipped the shit out of Brando. Literally. Sadistic. Tore the skin right off his back. Humiliated him in front of the whole town. Made an example of his lawless ways. The dream team of 50s and 60s westerns? Andrew Duggan, James Griffith, Robert J. Wilke, Gabby Hayes, and Walter Brennan, always aged, sons of bitches…foils, cranks, crotchety old men who were like good corner men in a prize fight.

Cowboys need sidekicks. Leo Carrillo, the jovial sidekick. “Hey Cisco.” “Hey Pancho.”

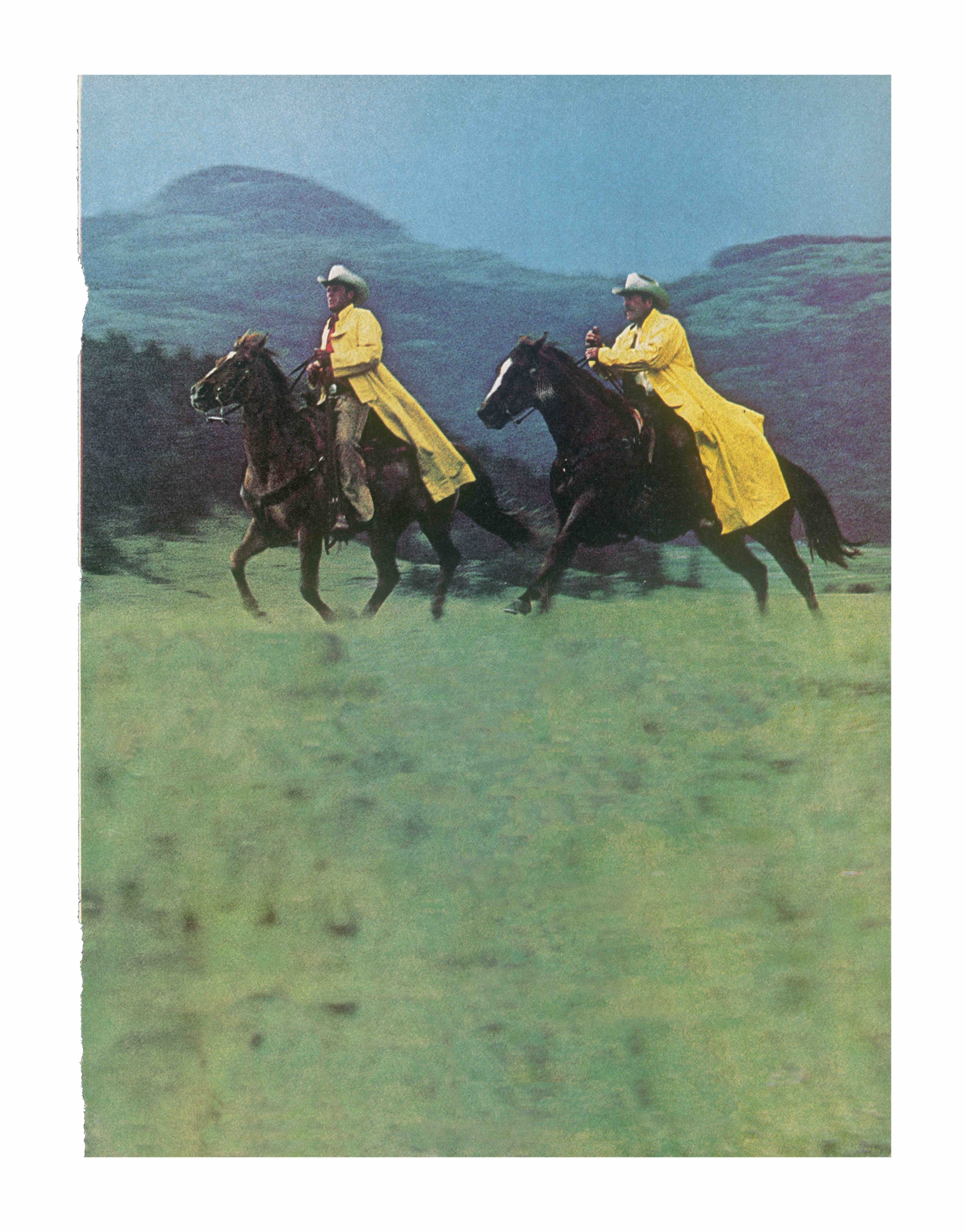

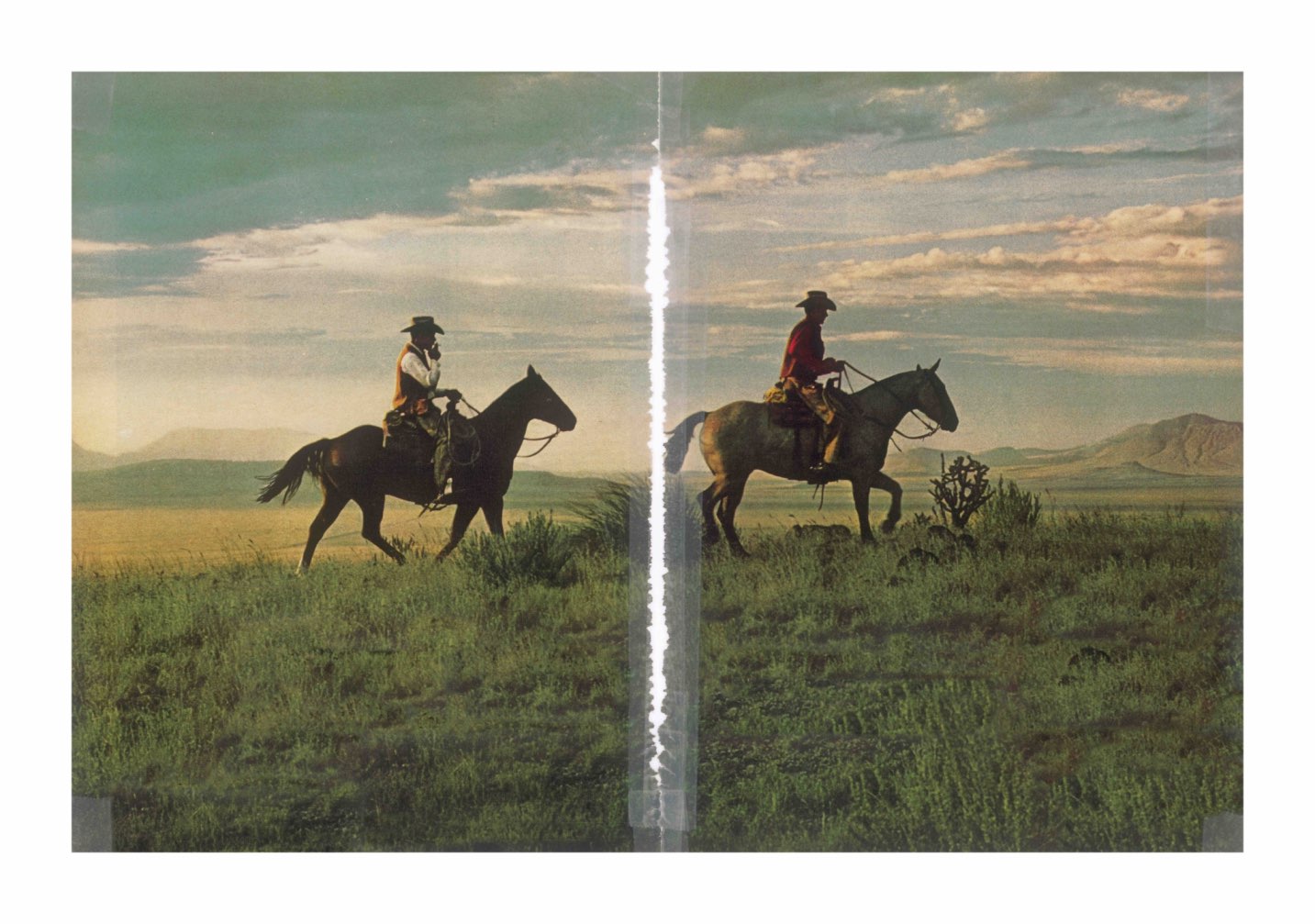

The Magnificent Seven. Third best on the list. James Coburn, Steve McQueen and my all time favorite, Charles Bronson. Each has a special subset of skills to make the seven into a complete team of bad-ass hombres. Hired guns. South of the border. No bench. All starters. All all-stars. Have Gun Will Travel. I’m not sure when I finally hooked into the Marlboro ads and started to see them as a way of presenting a group of work that was the same but different… like it was my own campaign. I had never thought about commonality like this before. I had never thought about sampling from the same maker, the same source. I think when I realised that Marlboro started using other models was when I zeroed in. The famous model with the mustache started fading out in the early 80s. When new models showed up I thought after I re-photographed the ad they were in…it looked less like what it had been originally intended for. It no longer had its signature. (What it was known for.) I thought maybe I could sign on and have a better chance of calling the photograph my own.

Untitled (Cowboy), 2016.

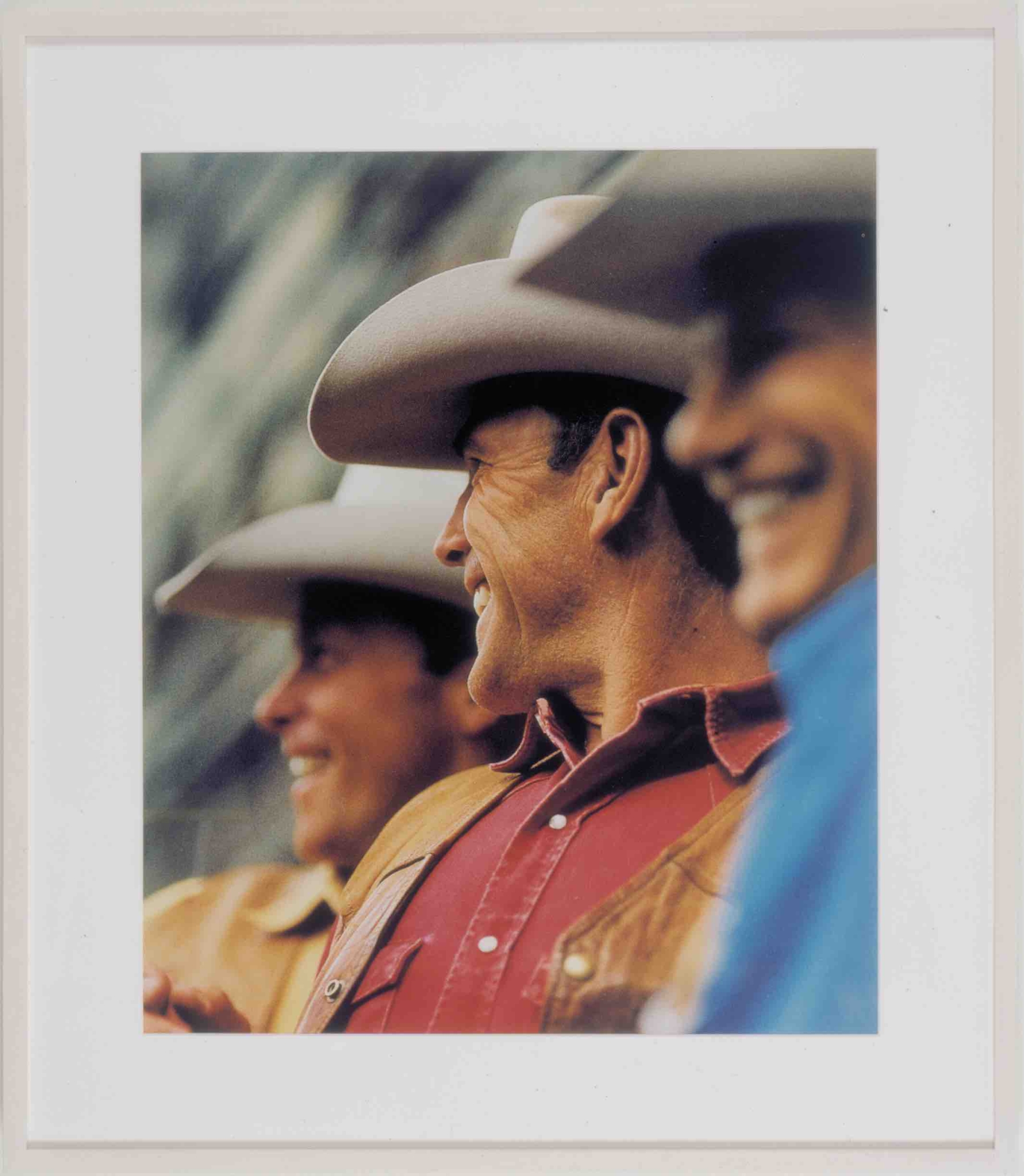

I didn’t know it at the time, but Marlboro’s whole campaign was based on a Life magazine article on cowboys that was a cover feature published on August 22, 1949—16 days after I was born. The cowboy on the cover was a close crop portrait. He was wearing a bandana and had a hand-rolled cigarette, just lit, settled into the side of his mouth. He was rugged, weathered, chiselled. He looked to be in his mid-forties. Handsome. Of course he had on a Stetson. His name was Clarence Hailey Young, a foreman at what use to be the JA Ranch in Texas. Clarence worked the Texas panhandle…“320,000 acres of nothing much.” Clarence was known to say things like, “If it weren’t for a good horse, a woman would be the sweetest thing in the world.” The photograph of Clarence was taken by Leonard McCombe.

It’s strange: the first thing that pops up when you search engine McCombe is his photograph of Young. The first sentence from the search engine: “If a picture is worth a thousand words, then Leonard McCombe’s image that inspired the Marlboro Man is worth over 15 billion.” Another strange detail? As far back as 1924, Philip Morris’s only customers were women. It wasn’t until the early 50s that Marlboro went looking for a new image to brand to a new market. In 1953, Leo Burnett, a Mad Man from Madison Ave got the inspiration from the McCombe photo and, based on the Young cover, pitched the cowboy idea to Philip Morris. The idea would eventually boost Marlboro “to the top of the worldwide cigarette market.” You can do your own search on all this “history.” If you do, plug in Leo Burnett. You’ll discover he came up with Tony the Tiger, Charlie the Tuna, the Maytag Repair Man. Great stuff. Important? Yeah it’s important. Leo’s my main man.

I bought a vintage copy of McCombe’s Cowboy. A gelatin silver print, print from circa 1954 at a Christie’s auction in London. This was a couple of years ago. I have the McCombe hanging in my living room next to one of my own cowboy photographs. In the Christie’s catalogue they mention my name when they describe McCombe’s photograph. How cool is that? I’m not sure when Marlboro took to the idea of selling their product based on the Western, but when they did, they started with illustrations of cowboys.

Untitled (Cowboy), 2011-2015

The Marlboro cowboys were all staged. The blend of fact and fiction didn’t demand any of my senses to try and figure anything out. I took their word for it. I didn’t care about disbelief. My past, my growing up, had been full of lies, innuendoes, half-truths. Their story, their “look,” looked perfect to me. I took their word for it.

Richard Prince

I’ve never been interested in the history of the Marlboro campaign. Maybe now, but back when I started to collect the ads I didn’t care about their business. My photographs of their cowboys weren’t about critique or theory or ideas. It wasn’t about what’s consumed or the culture of industry. I liked the way they looked. They looked like cowboys that had been idealised, not quite believable, but still, with a little suspension, I could wrap my head around the scenarios of riding the range, roping a steer, sitting around a campfire, the last round up, and living independently, on my own, sleeping under the stars, bonding with the natural order of the four seasons. (Of course when I was thinking of this, I was living in a railroad apartment on 12th and Avenue A, for $75 a month, taking a bath in the kitchen because that’s where the tub was.)

The Marlboro cowboys were all staged. The blend of fact and fiction didn’t demand any of my senses to try and figure anything out. I took their word for it. I didn’t care about disbelief. My past, my growing up, had been full of lies, innuendoes, half-truths. Their story, their “look,” looked perfect to me. I took their word for it. After I took their word, I figured you wouldn’t have to take mine.

What I tried to do is present the picture on the page as naturally as it had appeared in the first place. I didn’t want to change it. I didn’t want to remove or alter or paint or add or subtract. I didn’t want to aestheticise the cowboy. Recognition was enough. Its realness felt genuine. And even though it wasn’t real, it was real for me.

It was what I was used to. The appearance of real. Close to real. Better than real. Really real. I didn’t make it up. It was already made up.