Artist and technologist Rachel Rossin speaks to Lucca Hue-Williams about AI, embodiment, and the blurred edges of humanness. From machine learning models trained on her childhood drawings to paintings powered by reclaimed electricity, Rossin’s work redefines what it means to create. A conversation at the edge of the digital and the divine—for A Rabbit’s Foot.

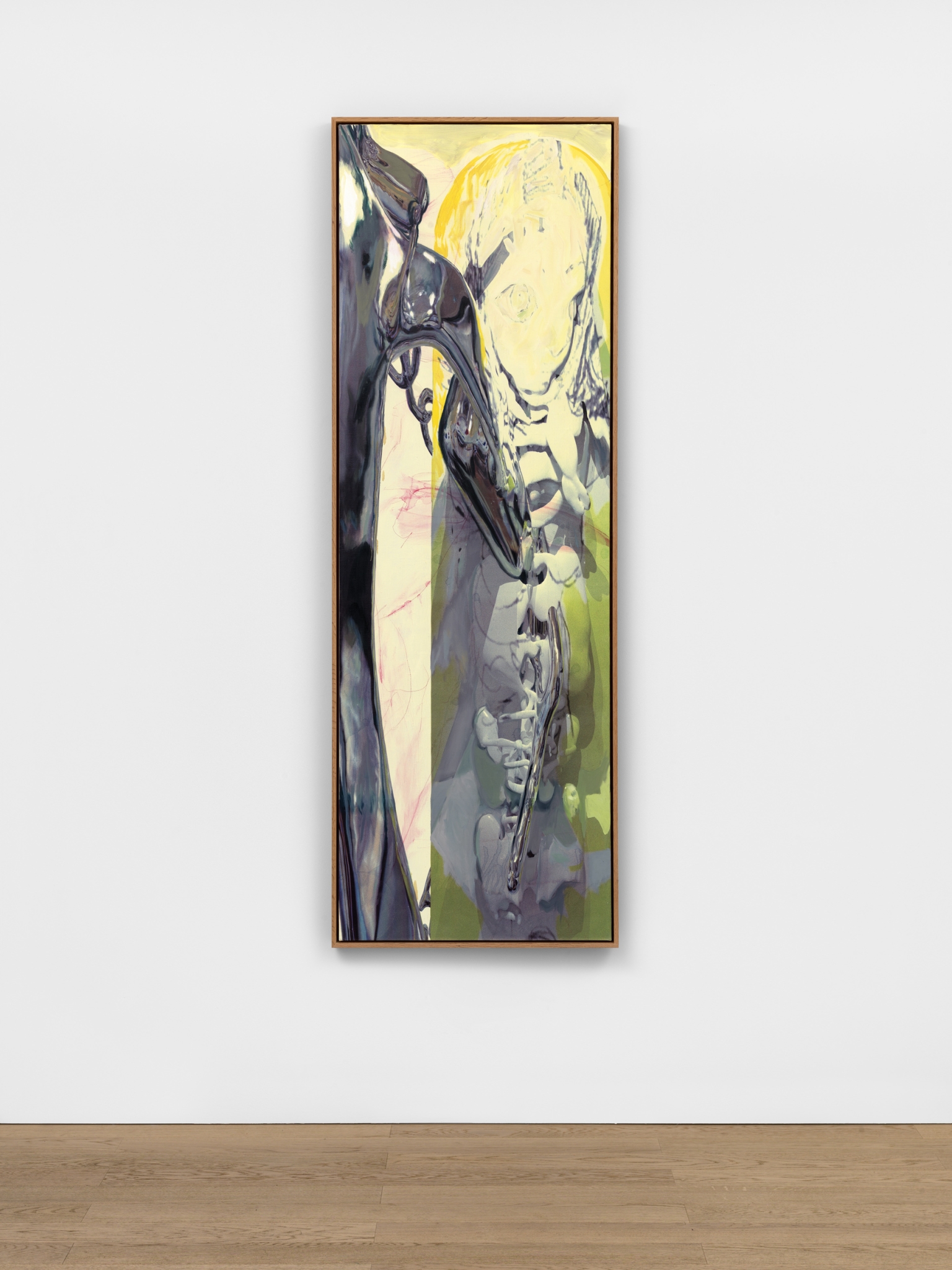

Siblings, 2025. Oil on canvas. 152 x 183 cm. Courtesy of Albion Jeune.

For A Rabbit’s Foot, Lucca Hue-Williams sits down with Rachel Rossin—painter, coder, and self-described cyborg—for a conversation that traverses the boundaries of art, technology, and the self. Rossin doesn’t speculate on the future of art; she inhabits it. Her practice dismantles the notion of technology as something separate from the body. In her hands, the digital becomes intimate, visceral—a mirror that reflects, distorts, and occasionally recognises us.

Drawing from both ancient oracular tools and contemporary machine learning models—some trained on her own childhood drawings—Rossin treats AI not as an end, but a medium. “A conversational mirror,” as she puts it. Her systems are built from scratch, her tools reprogrammed, and her process deeply embodied. Electricity is drawn from the air; a painting becomes a networked machine; a five-year-old version of the artist resurfaces in marks made by hand.

In this interview, Rossin and Hue-Williams explore the shifting role of the artist, the ontological implications of outsourcing cognition, and the strange, familiar ache of our co-evolution with machines. What emerges is a portrait of the artist not only as engineer or oracle—but as both. A conduit. A keeper of mystic truths. And someone still, definitely, in love with the image.

Lucca: Do you believe that the role of the artist is changing, specifically with regards to the intersection of art and technology?

Rachel: I do not believe the artist’s fundamental role is changing. However, I do believe the “artist” (as a human being—meaning, the artist and their respective ‘humanness’) is changing because what it means to be human has been shifting due to our dependencies on technology.

That’s where the conversation around AI’s impact on art should begin: the ontological definitions of human and art. For me, art is inextricably human. From that frame, AI is just a new tool—like the invention of acrylic paint was in its day.But as our technologies become more and more a part of us, what it means to be human begins to get blurry (see: transhumanism movements, or definitions of ‘cyborgs’). This, of course, alters how artists reflect the moment—but not why they make art.

Craft, though, will be essentially and irrevocably transformed by AI—which, for me, is distinct from art and has been since the industrial revolution.

I believe the role of the artist is defined as below:

“The role of the artist is to reveal mystic truths.” —Bruce Nauman

A conduit, in Marcel Duchamp’s sense: “To all appearances, the artist acts like a mediumistic being who, from the labyrinth beyond time and space, seeks his way out to a clearing.”

These roles persist, regardless of the medium. What evolves is the language of the work and its relationship to humanity, so it remains true to its era. Then the question can be: how much do we want AI to be a part of us?

Lucca: To that end, could you explain the AI model you have called the ‘guts’ of our show?

Rachel: I have trained a machine learning model on my own life’s creative output that has given me the ability to interact with versions of myself—but only in gesture (gesture meaning I’m making drawings) form. No text is ever involved. For example, I can make a drawing with my five-year-old self.

The logic of that model’s predictive capability is built with Frankenstein parts taken from open-source repositories—most notably Google DeepMind’s AlphaFold, an artificial intelligence program built to predict protein folding to understand how all of life’s molecules interact.

AlphaFold is unbelievable—an epoch-defining scientific revolution. I recommend everyone reading this look it up.

Lucca: Could you walk us through some of the visual lexicon and motifs in your work, like the oracle references and the mechanical heart?

Rachel: My piece, Telos, features a mechanical heart surrounded by ten darkened glass tablets reflecting references to the other paintings in the show. The ancient Greek word telos, in the Aristotelian sense, defines this as a being’s ultimate purpose—e.g., “the telos of the eye is seeing.”

I believe it is an avatar for our collective co-evolution with technology and a reference to the effort of training a system on my own teleology. I love this painting—I think it’s just delightful and I like its attitude.

One of the other motifs in the show has to do with AI as a material/medium and its relationship to us as a mirror. One easily forgets that AI is trained on human data and thereby exhibits fundamental flaws. Why are people surprised when an AI is misogynistic or racist? That is the modus operandi for human beings on the internet.

There is a sort of sweet coincidence in the nomenclature of “black mirror” related to this. Historically, darkened glasses (as most famously described in 1 Corinthians 13:12—“For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known”) have been found as far back as 3000 BC in Babylon (as well as in parallel cultures and traditions worldwide) and were used by oracles to communicate with the divine.

Blackened mirrors were how people saw the future or the past, how they consulted nonhuman powers. How funny that in technology we have invented that for ourselves and are now co-evolving with it. I wonder sometimes if this is a type of primal/primitive ache—yearning for a higher power in the form of a portal.

Lucca: To follow on, do you think AI has the potential to prevent people from interacting authentically?

Rachel: Yes. I love that there is, in most people’s nature, an instinct to look for falsehood or imitation.

There’s this tension with truth and fidelity now—every time I watch a video or read a sentence, I wonder, “Is that AI?” That sense of the unheimlich (German word for the uncanny, derived from the word for homesickness) fuels my own inquiry and art practice already. It is my own existential currency.

Was Marshall McLuhan correct when he said that for every technology we invent, we self-amputate that corresponding part of ourselves? Is this why I depend wholly on my phone for navigating a city or remembering phone numbers?

We have outsourced that to technology, amputating our own cognitive and psychological faculties. I suppose we will all learn together what the results will be from outsourcing our cognitive labour. It is cognitively cheaper for us—but what do we exchange for it? I’m curious if this will continue to feel tenable, and I hope it doesn’t take a cataclysm to make us investigate.

Lucca: Yes, this seems to be one of the more negative effects of AI. Can you talk about why AI is often presented in a dystopian manner?

Rachel: The Turing Test is humanity’s current shibboleth for human intelligence. It essentially says: if this AI can trick a human into thinking it is human, it passes.

It is pretty outdated—and, of course, many of today’s AI models have long since passed the Turing Test. So here we are, and it’s only just going to get weirder.

For example, now we are getting to see emergent technologies rising up to make new definitions of humanness. My recent favourite one is Sam Altman’s retinal scanning blockchain in order to verify that you’re human.

To be human in that system, you must have irises.

Lucca: Very interesting. Could you talk about your work that sources electricity from the grid?

Rachel: Well, there is an enormous amount of waste energy in electromagnetic emissions like Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and satellite signals, etc. I’m prototyping rectifier circuits using crystal diodes to reclaim tiny amounts of that radio frequency energy and turn it back into usable electricity.

This process makes tangible the ubiquitous but invisible currents of energy which carry our data. It is very small amounts of electricity taken from the “air” to power small new media works that a grant from Creative Capital has made possible.

Lucca: It’s fascinating how art, technology, embodiment, and even ecology all intertwine in your work.

Rachel: Totally. I don’t believe in silos. It doesn’t feel true to how I experience the world, and so I don’t want to ask my art to do that either. I’m interested in all of it and try to maintain a protean curiosity in my practice.

Lucca: Could you explain the relationship between the analogue and the digital in your work, between the immaterial nature of AI and the material result of paintings?

Rachel: I find people often misunderstand how I use AI. It isn’t a substitute for my own work or process—it’s a conversational mirror.

Lucca: How much control do you have over the generative aspect of your practice?

Rachel: I have 100% control because I created the entire system. It is a soup-to-nuts operation. The predictive logic, although extrapolated from open-source repositories, is inherited from previous things I’ve made.

Lucca: Given that A Rabbit’s Foot is a film and culture journal, there’s a lot of interest in how cinema is grappling with emerging technologies like deepfakes, synthetic actors, and AI-generated scripts. As an artist working with machine learning and embodiment, how do you see these tools influencing—or perhaps disrupting—narrative and performance in film?

Rachel: Oh goodness, all of this will be completely transformed and it will move very fast. It will be interesting to see how regulation evolves with this as that will be the only limit. Already today you can download a stable diffusion model of virtually any celebrity: https://shakersai.com/ai-tools/images/stable-diffusion/best-stable-diffusion-celebrity-models/. You can clone any voice and you can prompt into existence special effects compositions that would have cost millions to produce.

Lucca: Alright, let’s wrap up with something fun—if you had to recommend three films every cyborg should watch, what would they be? And what films shaped you, or shaped your thinking about technology, identity, and embodiment?

Rachel: Synecdoche New York, Satoshi Kon’s Paprika, Serial Experiments Lain.

Lucca: For my final question, I wanted to ask who your creative inspirations are, considering this kind of technology (in the way that you use it) has come into being relatively recently?

Rachel: Maria Lassnig, Gretchen Bender, Nancy Holt, Paul Thek, Ashley Bickerton, and Robert Smithson.