At Albion Jeune, a new exhibition between two contemporary artists ‘creates a space for contemplation’, inviting the viewer into nature through work informed by traditional Chinese painting.

Located just off Regent Street, removed from an endless sea of shoppers, to enter Albion Jeune is like stepping into an oasis of calm. This is thanks in large to the gallery’s new show, The Garden and The Gaze, consisting of works by two contemporary Chinese artists, Feiyi Wen (b. 1990, Beijing) and Xiaochi Dong (b. 1993, Shanghai), whose work commands silence.

The collection of just over 20 works is overall muted in tone, and quietly powerful. As I walk around the room, I can see the debt owed to traditional Chinese landscape painting, and also feel it, in the works’ aura. Just as I am about to inspect Xiaochi Dong’s Green Cube up close, I am told that the two are waiting to speak to me.

It becomes apparent that the two artists hadn’t met prior to Lucca Hue-Williams, the gallery’s founder and director, proposing the joint exhibition, but you’d be mistaken for thinking they are old friends. There are certainly strong parallels between them in their personal lives, from growing up in mainland China in the 90s, to studying in London at The Royal College of Art, and in their artistic influences, even though they work in different media.

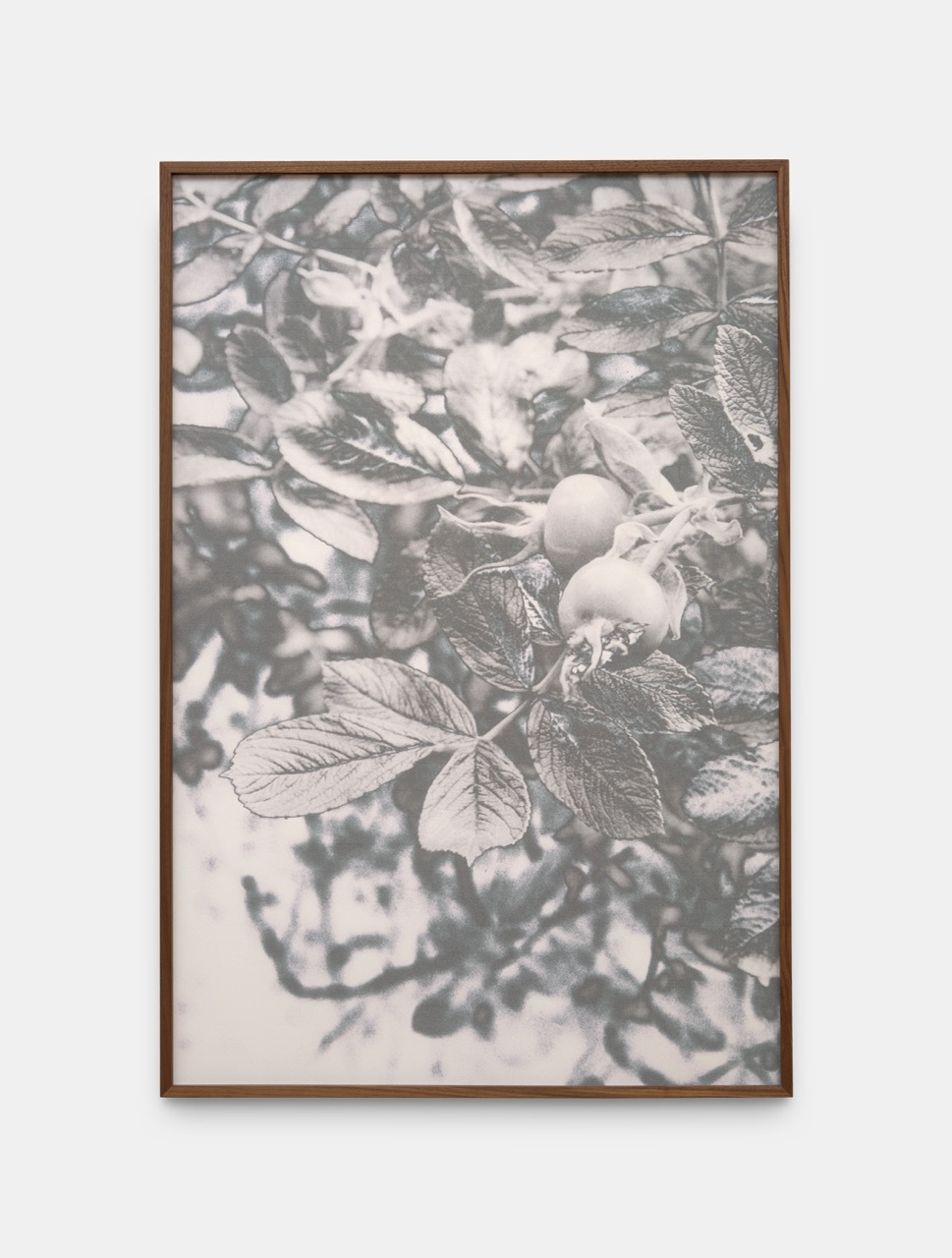

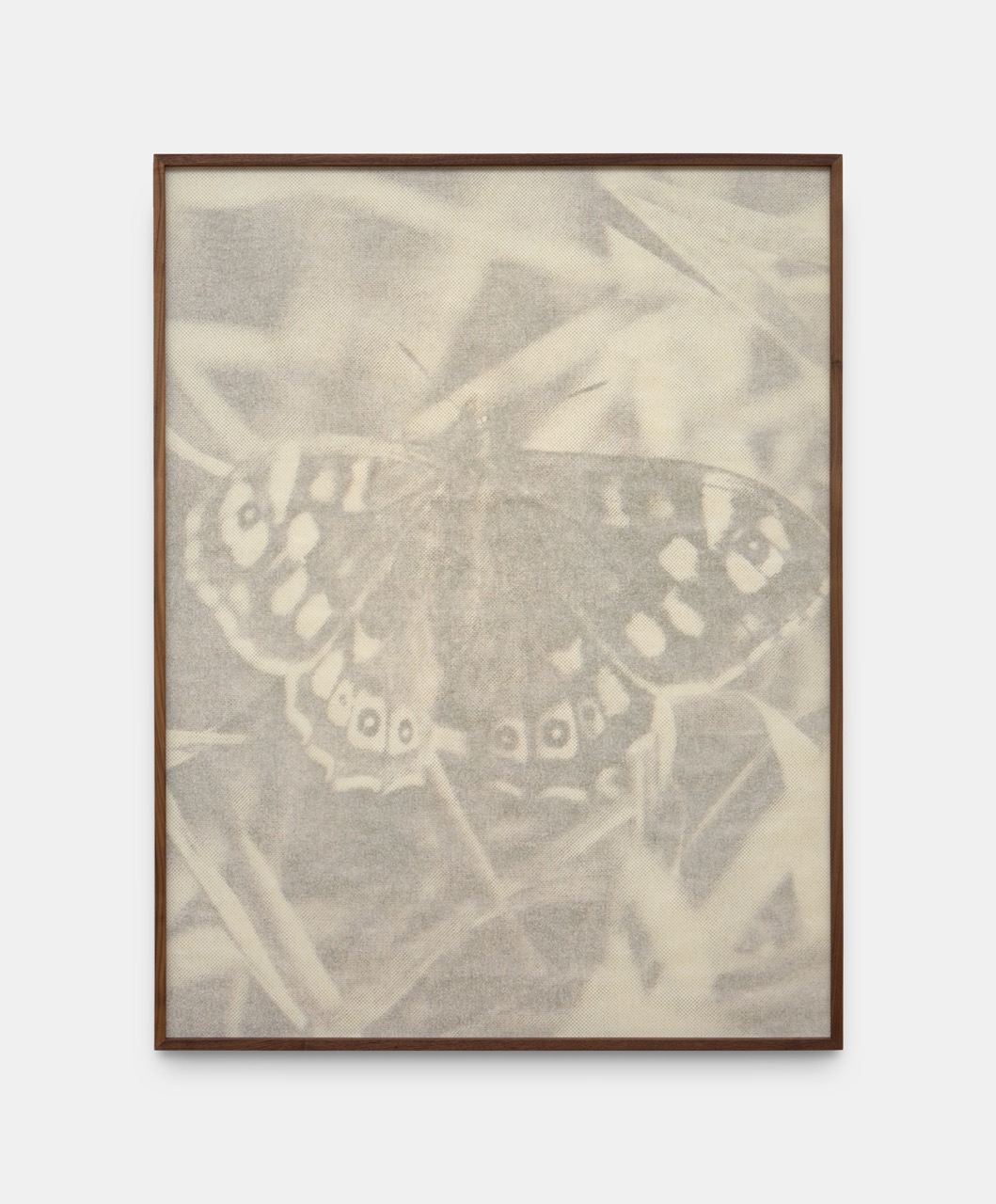

Feiyi Wen is a photographer, who subverts the medium’s precision through repeated scanning and reprinting. She prints her images on rice paper, a material synonymous with traditional Chinese painting, showing that her practice is experimental, and still rooted in history. The overall effect of her work is one of flatness, due to her rejection of traditional Western one-point perspective. This rejection, combined with her experimentation with images, gives her pieces a painterly, romantic quality that invites contemplation.

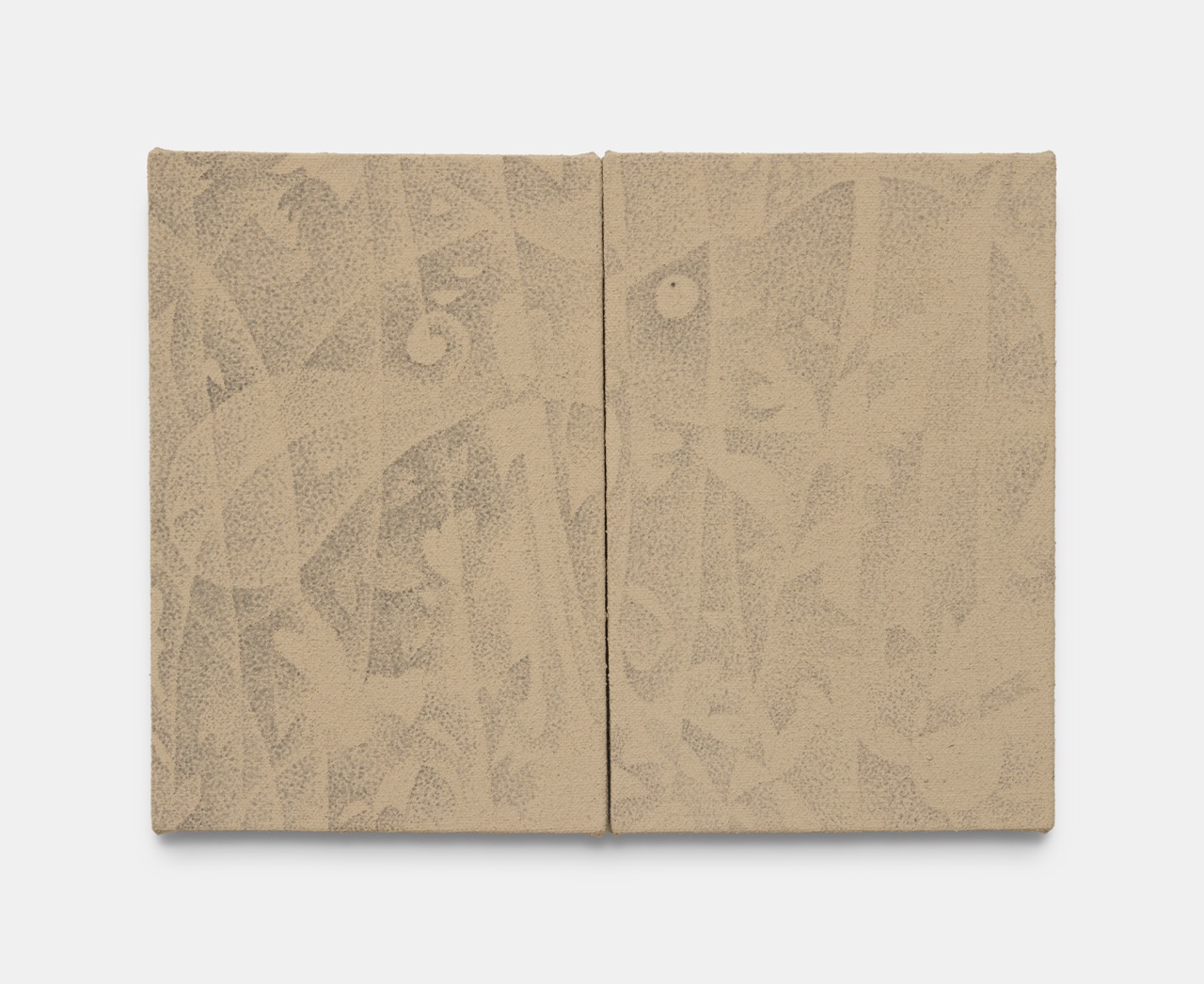

Xiaochi Dong, Green Cube, 2025. Courtesy the artist and Albion Jeune Photography by Tom Carter

Similarly, Xiaochi Dong takes inspiration from Shan sui, or mountain-water landscapes, which date back to the 5th century. His mixed media pieces emulate their emotional effect, while experimenting with materials personal to him. Notably, his use of Japanese Akadama soil, the base he paints on top of, which he happened upon through his love of terrariums and keeping amphibians and reptiles in his London home, which he discusses excitedly. The result is that of rough, textured panels, mimicking the habitats he creates for his animals.

A difference between them, however, is their interest in location. Wen invites the viewer to look at the beauty of the subject matter, without thinking too much about where the original image was taken, which she admits is difficult with photography. Whereas, Dong is obsessed with two locations, Kew Gardens and Derek Jarman’s Prospect Cottage, with the dimensions of his panels being drawn from The Waterlily House at Kew, and the windows of Prospect Cottage.

Despite this difference, The Garden and The Gaze is a dialogue, with both artists creating work devoid of human figures, inviting the viewer to reflect on their relationship with nature.

Our conversation spans many subjects, from the impact of growing up in the city, the importance of the natural world, to the films they go back to for artistic inspiration.

Claire Sandford: Can you tell me how this joint exhibition came about?

Feiyi Wen: Lucca suggested that Xiaochi and I do an exhibition together and I was very pleased because it felt like a great fit. The thing about having a two person show is that it has to be a dialogue between two artists’ work, it can’t just be putting two people together.

Xiaochi Dong: When they reached out to have a two person show, I thought it was a great idea, because before Lucca connected us, we followed each other on Instagram so we were already familiar with each other’s practice, and our content and our direction matched.

CS: Seeing your works together, I’m aware that material is extremely important. Do you mind telling me how you came to find your dominant medium?

FW: My background is in photography. When I moved here, I did my Masters at The Royal College of Art and I started to see different approaches to photography, but I was still predominantly doing darkroom printing.

I shifted my practice when I was at Slade doing my PhD. I became more interested in experimentation, with the printing, and the techniques of not only the image, but working with the image. It became more about having the source image and making something completely different from it. So that’s when I started experimenting more on different surfaces and techniques.

I use rice paper for my work, which is the material used in Chinese structural painting, and you can see from the subjects I depict that there is reference to these paintings. I suppose there is a parallel with my own photographic practice and traditional Chinese painting from art history.

I guess that’s also why it’s very appropriate for us to be in the same show because Xiaochi’s background is in traditional Chinese painting.

CS: Xiaochi, can you explain the importance of traditional Chinese painting and techniques in your work, especially cun (textured) and dian (dotting) brush methods?

XD: I was studying traditional Chinese painting in Shanghai for nearly ten years for my BA and MA, and during this period people would always ask how this kind of painting influenced me, but it’s less about its specific techniques and more about the inner energy that these paintings bring that influences me.

In my practice I use special techniques from traditional Shan shui landscape painting, that means mountain-water painting, which is kind of similar to pointillism, except we use ink. The way I use it is cun and dian, which means texture and most dotting brushstrokes.

At the moment, my focus is on terrariums and the greenhouses of Kew Gardens, and when you look through the windows of terrariums or greenhouses, there’s always a lot of moss that grows on the glass, and the dian, or most dotting technique, matches this texture.

CS: I know you love amphibians and reptiles. How many do you have in London, and how does the way you create their habitats relate to the set-up of your work?

XD: The number might sound crazy, but because they are very tiny, I have more than 10 dart frogs and more than 10 chameleons in London. The type of chameleon is called Brookesia; I think they’re the most tiny chameleon in the world. It’s because of them that I use Akadama soil in my work.

When I came to London, I felt I needed to jump out of my comfort zone because I used to practice on rice paper. I wanted to do something experimental, something new, on some new material. I think I chose Akadama soil because it’s a natural substance that I use a lot, like for my terrariums, so it is everywhere in my living space.

My painting is like the landscapes I want to set up, so I thought, why don’t I use this material in my painting? As a result, the work is like a growing garden on linen with the Akadama soil base, and painting on the surface.

CS: You both grew up in cities, do you think this has altered the way you view and depict nature?

FW: I grew up in Beijing.

As a child my grandma would take me to different parks where you would see a lot of interesting things, such as miniature Chinese landscapes, with small stones and man-made fake mountains. I always found them interesting because growing up in the city makes it hard to see the real landscape, like the mountains and the sea, but you can still see the miniature version of it.

I suppose there is a lot of imagination involved because I think as people, we are very drawn to nature but when you grow up in a city, it’s limited.

It’s an interesting perspective because I didn’t grow up in this real, natural landscape so I have an emotional attachment to the natural world, but a lot of this is my imagination, rather than the real thing.

People normally see photography as representational, which is different from painting and sculpture, and are interested in the location of the photograph. However, in my work, I’m trying to move away from the specifications of the space or location, it’s more about an idea and emotion, not where the photograph is taken.

CS: And how about you, Xiaochi?

XD: I think growing up in Shanghai is the reason I like amphibians and reptiles.

I’m interested in their natural habitats and ecosystems, and as a child, I would set up fishtanks and terrariums. As Shanghai is a big, built-up city, I didn’t have much experience with tropical and wild jungles for example, but keeping these animals allowed me to experience different types of environments in my living space.

CS: Derek Jarman’s Prospect Cottage plays a pivotal role in your work, Xiaochi, do you remember the first time you learnt about it, and how its influence, along with Kew Gardens, has influenced the dimension of your work?

XD: In my second year at the RCA, my tutor, Steve Claydon, told me that there was a rocky garden in a place called Dungeness. Before this, if you mentioned a rock garden, I would imagine a Japanese-style garden.

Before I visited his (Derek Jarman’s) garden, I bought his book called, ‘Modern Nature.’ This book is very interesting because it’s a daily record of how he found this place and how he set up his garden to look as it is now. I felt I had to see it in person.

I went to his garden and found it very interesting because even though Dungeness is by the sea, it’s like a desert reserve by the sea, with a nuclear power station very close by. I often wonder why Derek Jarman chose this place to spend the end of his life because he was very sick at the time.

I would like to go to his garden two to three times a year to feel it in different seasons. This year I had a solo in Beijing and when I was preparing the solo, I spent around ten days in Dungeness.

In my painting, each panel is drawn from the size of the glass wall in Waterlily House, in Kew Gardens, or the window size of Derek Jarman’s Cottage. I use these specific sizes because I want to create an entrance that allows the viewer to feel a part of that place.

This kind of spiritual journey is also in traditional Chinese mountain-water landscape paintings, because they don’t just offer a view, it’s kind of like a memory of that journey. So you cannot see the real mountain in the painting. So this painting offers people to get into this journey, but in a spiritual way.

FW: It’s like an inner landscape, I think.

XD: Yes, it is an entrance for people to get into the mountain, and my work is for people to get into Kew Gardens or Derek Jarman’s Garden.

“Growing up in the city makes it hard to see the real landscape… I have an emotional attachment to the natural world, but a lot of this is my imagination.”

Feiyi Wen

Feyi Wen

CS: Is there a film that you go to for creative inspiration?

FW: I watched quite a lot of Yasujirō Ozu films when I was at university. I can’t really think about any particular film to be honest because it feels like they blend into each other because their plots are often quite similar. I think it’s more the way he used light, long shots of objects and the outside landscape to convey human emotions. That’s one of the things I often get to go back to; I often rewatch those films.

Also, the films of Chinese director, Fei Mu, who made most of his work before 1949, before Communist China. His work drew on quite a lot of Chinese traditional painting and poetry.

One of my favourite films by him is called Spring in a Small Town, which I think has been re-issued by the BFI, so it’s a classic. I’m more interested in its visuals, rather than the plot, because he uses imagery from traditional Chinese poetry such as shots of moonlight and candles. All of these things about light and shadow and the nature of the landscape may seem like the backdrop to the film, but at the same time it’s a major part of it. All these elements are visuals I go back to in my work, so it’s an inspiration.

CS: How about for you, Xiaochi?

XD: Can I say a documentary? Because there is a documentary called Kingdom of Plants, which is all about how plants grow and how they fight for nutrients in Kew Gardens. Normally we can’t see plants moving, but this documentary uses a technique to show how the plants fight, just like animals.

CS: Feiyi, do you think the violence of nature fits into your work?

FW: This is a difficult question, because I focus on the aesthetic.

Of course, nature isn’t just beautiful flowers, plants and trees, a lot goes on beneath the surface that can be quite violent. But my own approach is to create a space for contemplation and invite people to be in this nature.

This is why there is an intentional absence of human figures in my work. I’m actually using a framework of ‘one body’, which is the Chinese philosophical concept of the interconnectedness of all things, so it’s a non-dualistic view of humanity and the natural world.

The Garden and The Gaze is on at Albion Jeune until 31st January 2026.