As a new show considering the auteur’s paintings, sculpture and short films opens at Pace Gallery in Berlin, Sayori Radda dives into David Lynch’s artistic practice, exploring what it reveals of his enigmatic mind.

“I believe life is a continuum, and that no one really dies—they just drop their physical body and we’ll all meet again.” These words, spoken by David Lynch, capture the transcendence that inform both his life and work. Last week marked the birthday and first anniversary of the passing of Lynch—a singular, boundary-defying filmmaker, artist, and musician whose evocative work continually blurred the line between familiar and uncanny.

In homage to his legacy, Pace Gallery—his longtime collaborators in his artistic career and representatives since 2022—this week will unveil the first solo exhibition of his artistic practice, David Lynch, at Tankstelle in Berlin. The exhibition promises around 25 works encompassing the full breadth of his striking artistic oeuvre—paintings, drawings, watercolours, photographs, sculpture and an early short film— leading up to a monumental exhibition in Lynch’s hometown of Los Angeles, at Pace later this year.

Lynch’s discipline and passion for the fine arts cannot be overstated. In Lynch on Lynch (1997), editor Chris Rodley asks whether painting is “the primary activity… from which everything else comes”—Lynch responds affirmatively, adding that, “There are things about painting that are true for everything in life… it is the one thing that carries through everything else.” Long before he became a filmmaker, he was a self-taught artist, drawing and painting as a child in a makeshift home studio set up by his parents in rural Montana and Idaho, which would be formative for Lynch. “His father worked for the U.S. Forest Service, so he was going out into the woods, and his interest in language was sparked through his mother, who was a language teacher,” Genevieve Devitt Day, senior director of Pace Los Angeles was told by Lynch. It was under these circumstances, that his “creativity exploded unencumbered—unusual for somebody growing up in rural areas with little cultural references,” she continues. “If you look at his work over the decades, it is less about external references and more about subjective inner experience. While he has spoken about engaging with painting and Surrealism, these were less direct influences than formative touchstones during his student years—elements that ultimately evolved into the wholly unique vision we now recognise as Lynchian.” Bill Griffin, managing partner at Pace Los Angeles, who worked closely with Lynch for over 15 years, notes that his early drawings demonstrate remarkable mastery of representation, composition, and line—proving that Lynch was “far from the outsider artist who doesn’t know how to draw.”

Though critical of academic structure, describing school as having “destroyed the seeds of liberty,” Lynch’s creative beginnings were shaped within a more institutional framework. He studied painting briefly at the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design in Washington, D.C., before enrolling at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in 1965, leaving both programmes early. By 1966, a decisive turning point emerged during his studies at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts: There, he developed a deep engagement with dark subject matter and began the pivotal transition from painting to moving image. “Of course, he understood, studied, and was deeply aware of European modernism and art history, and there were artists he genuinely admired. However, he was largely uninterested in the contemporary art world. Instead, he was deeply engaged with developing his own ideas—ideas that aimed for a universal connection to the human condition. David’s work was intended to be universal and open to interpretation,” notes Bill Griffin.

The idea of movement within a work famously appeared to him when a gust of wind shifted one of his paintings, marking a turning point that set him on a trajectory into cinema. This culminated in his first short film, Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times) (1967)—a four-minute animated painting with the sound of sirens on loop—which won the annual painting-and-sculpture competition at the Academy. Selling the piece for $1,000, Lynch invested in his next four-minute short film, The Alphabet (1968), allocating half of the proceeds to purchase a film camera and the remainder to fund production. Straddling the line between painting and fiction film, and inspired by a family member’s nightmare in which the alphabet is repeated relentlessly, The Alphabet serves as an entry point and the curatorial theme of Pace’s exhibition.

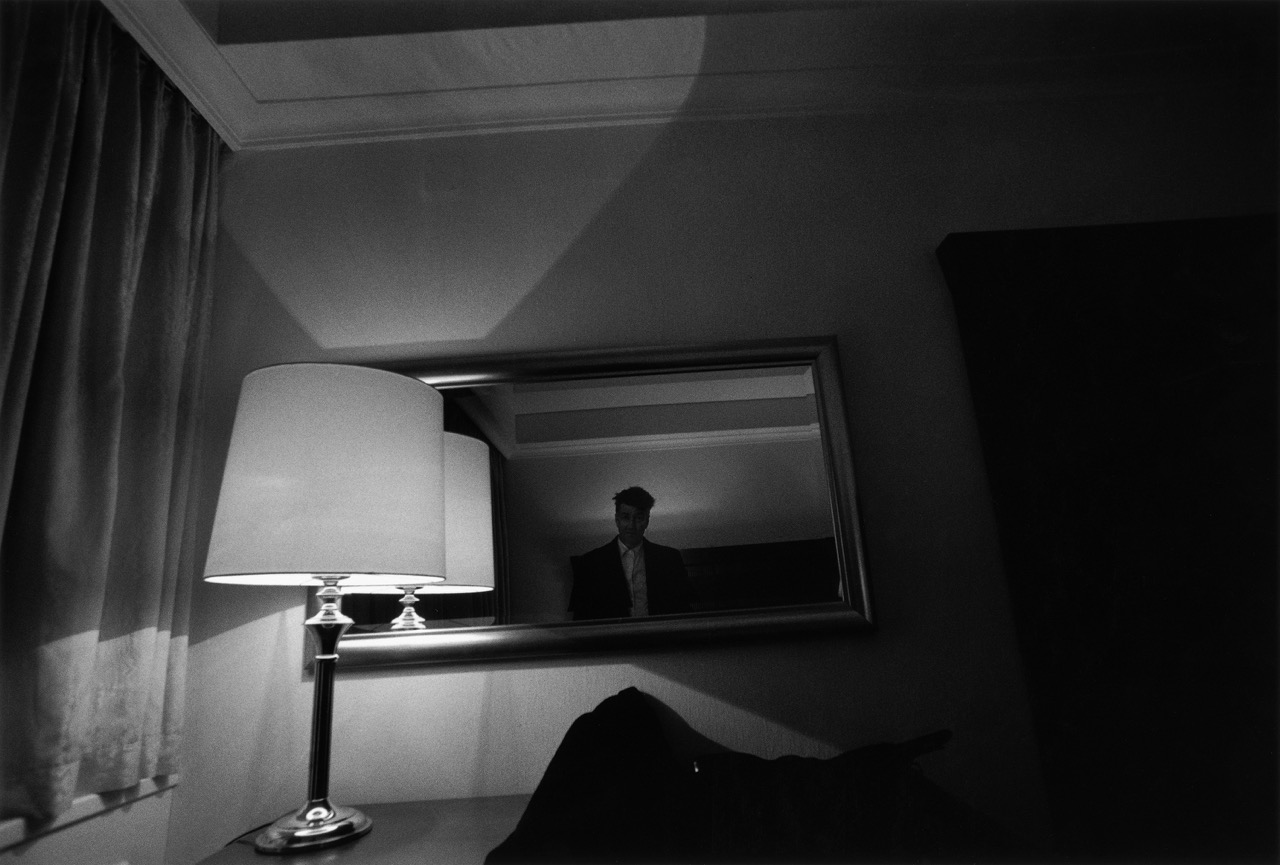

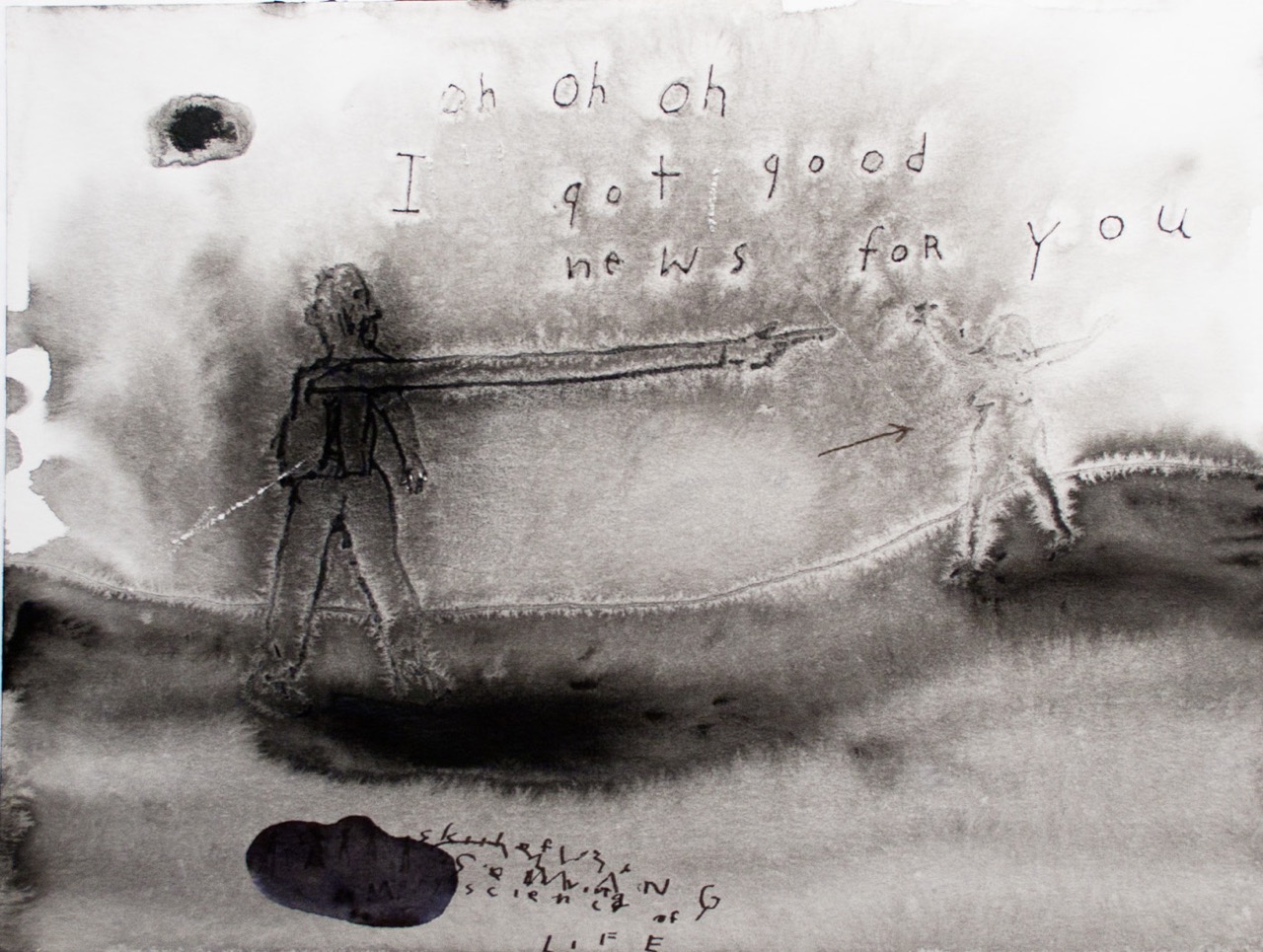

“Words, jokes, dialogue—language is always present—accordingly, the exhibition explores the spatialisation of an anxiety around language that reverberates across all the mediums Lynch worked in,” says Pace chief curator Oliver Shultz. The paintings depict disordered letters, fragmented sentences, or bodies that defy resolution, remaining ambiguous and absurd. “You’ll see Lynchian characteristics in The Alphabet, that you’ll recognise in his paintings throughout the show,” notes Devitt Day. Fractured, cut-out letters affixed to the canvas, for instance, recall the antagonist Bob in Twin Peaks, who places letters beneath his victims’ fingernails. “You can see parallel character development within his films and paintings, where one can find similarities—but he mentioned they aren’t directly related,” she continues: “They’re all going to be under the same Lynchian universe, as they were created by him, but Lynch wanted it to be very clear, that his film practice was separate from his fine art practice.”

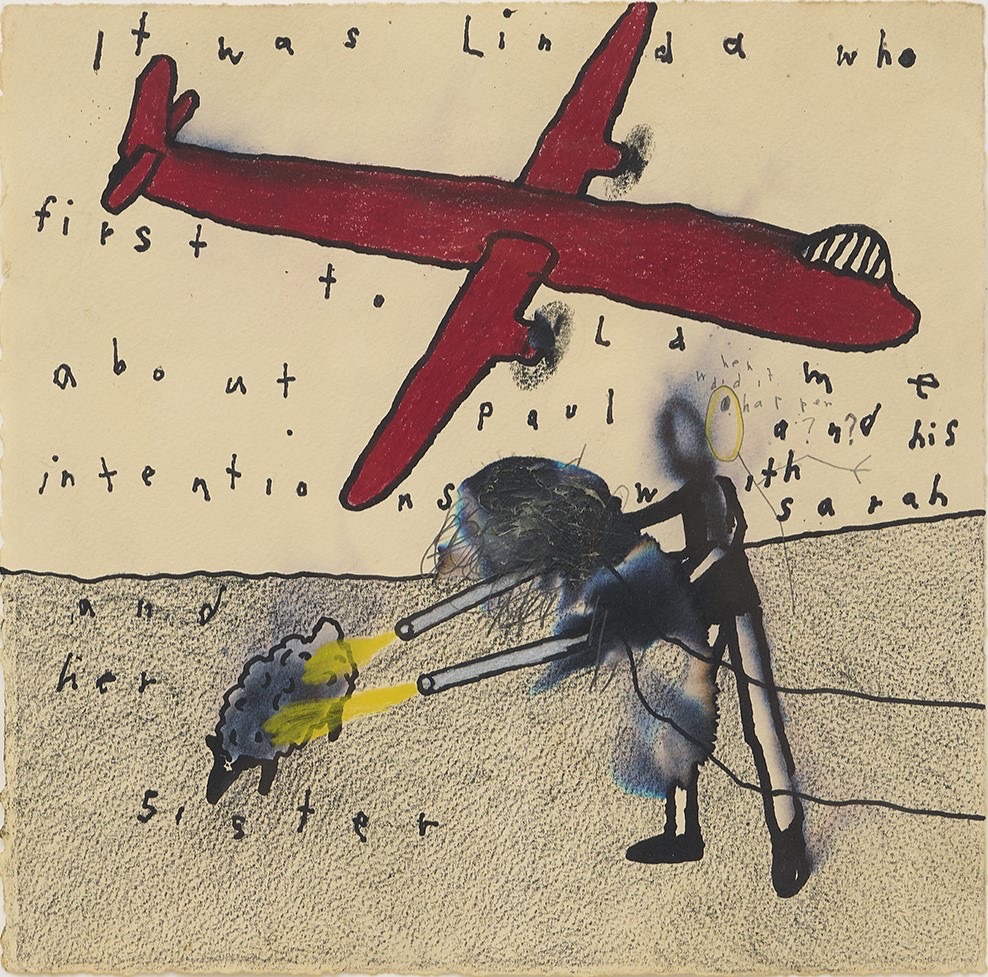

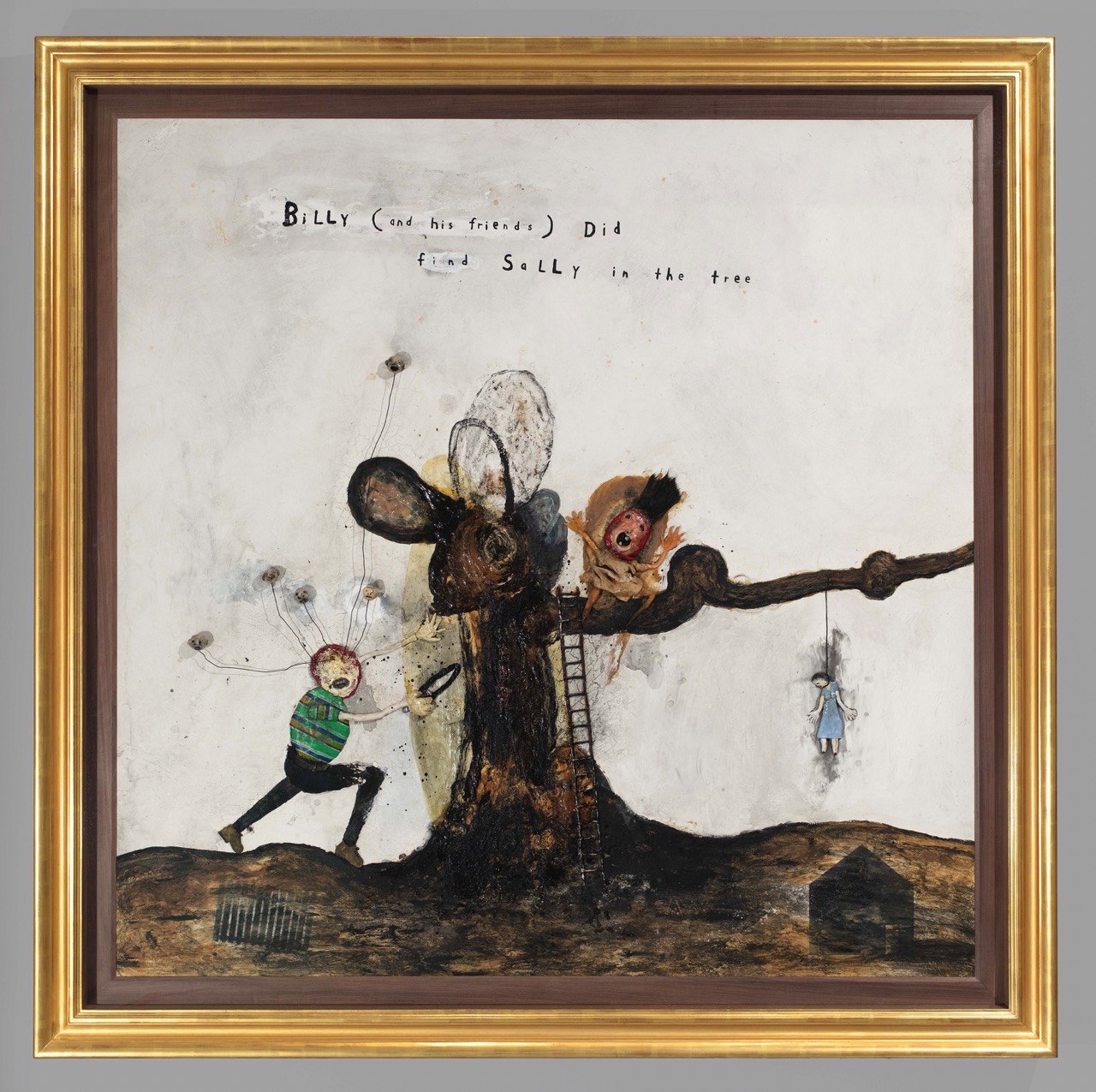

David Lynch, untitled (Berlin), 1999 © The David Lynch Estate, courtesy Pace Gallery

In Billy (and His Friends) Did Find Sally in the Tree (2018), a mixed‑media painting whose title is hand‑inscribed across the canvas, Lynch explores narrative ambiguity through a surreal tableau of anthropomorphic figures. In Lynch’s paintings, Billy is a recurring emblem, a fluid and enigmatic presence that appears across multiple works. When asked about Billy, Lynch noted, “In one thing, he can be one way, and you’d feel that. In another, Billy can be quite a bit different, and you’d feel that in the painting.” The name also evokes Bill Hastings, an unseen but frequently discussed character in Twin Peaks: The Return (2017), whose identity and whereabouts remain an enigmatic mystery. In the painting, Billy appears alongside Sally and her companions, in which a tree takes on the form of a rabbit, recalling the recurring motif of anthropomorphic rabbits in Lynch’s Rabbits (2002) avantgarde horror series, thereby reinforcing the work’s dreamlike tension between narrative suggestion and visual abstraction.

From Lynch’s perspective, words alter the perception of a painting—through etymology, visual form (Lynch gave Rodley a particularly surreal example of teeth emerging from cut-out letters), or by functioning as the title itself. “He always talked about wanting paintings to tell a story,” Devitt Day recalls. “Even though it was very subjective and internal, he wanted viewers to engage with the work.” For Lynch, the figures that populate his paintings are “fragments of a body”—never whole—and are consistently accompanied by a dark palette, as colour is, to him, too “real” and limiting. “The paintings have a fearful mood, but there’s humour in them too,” Lynch tells Rodley. “Ultimately, I guess the central idea is, you know, life in darkness and confusion.”

Whereas his paintings are devoid of place and situated in a murky, abstract void, his films tend to take place in an estranged, illusory America—like Twin Peaks (1990), set in a fictional town in Washington, or the fabricated Lumberton in North Carolina, from the 1986 neo-noir mystery Blue Velvet—where time and place fold in on themselves. Whereas films include layers of construction and collaboration, his artistic practice appears to him directly through the subconscious, bleeding onto the canvas through automatic painting and surrealist expressions—“There’s no storyboarding a painting or watercolour—he [was] very much in front of it, drawing and painting day in, day out,” Devitt Day affirms. This viscerally driven, direct, and abstracted painterly approach is most visible in Tree at Night (2019), a mixed-media painting rendered in a visceral palette of bleu-noir, evoking the depths of the night sky against a corporeally twisted, emanating body enmeshed and floating somewhere between tree and sky. Regarding the work, Devitt Day notes, “He never referenced this directly, but for me there’s a very Duchampian feeling to it, which harks back to what he knew of Duchamp living in Philadelphia. I think the relationship to Surrealism is most overt in this painting.”

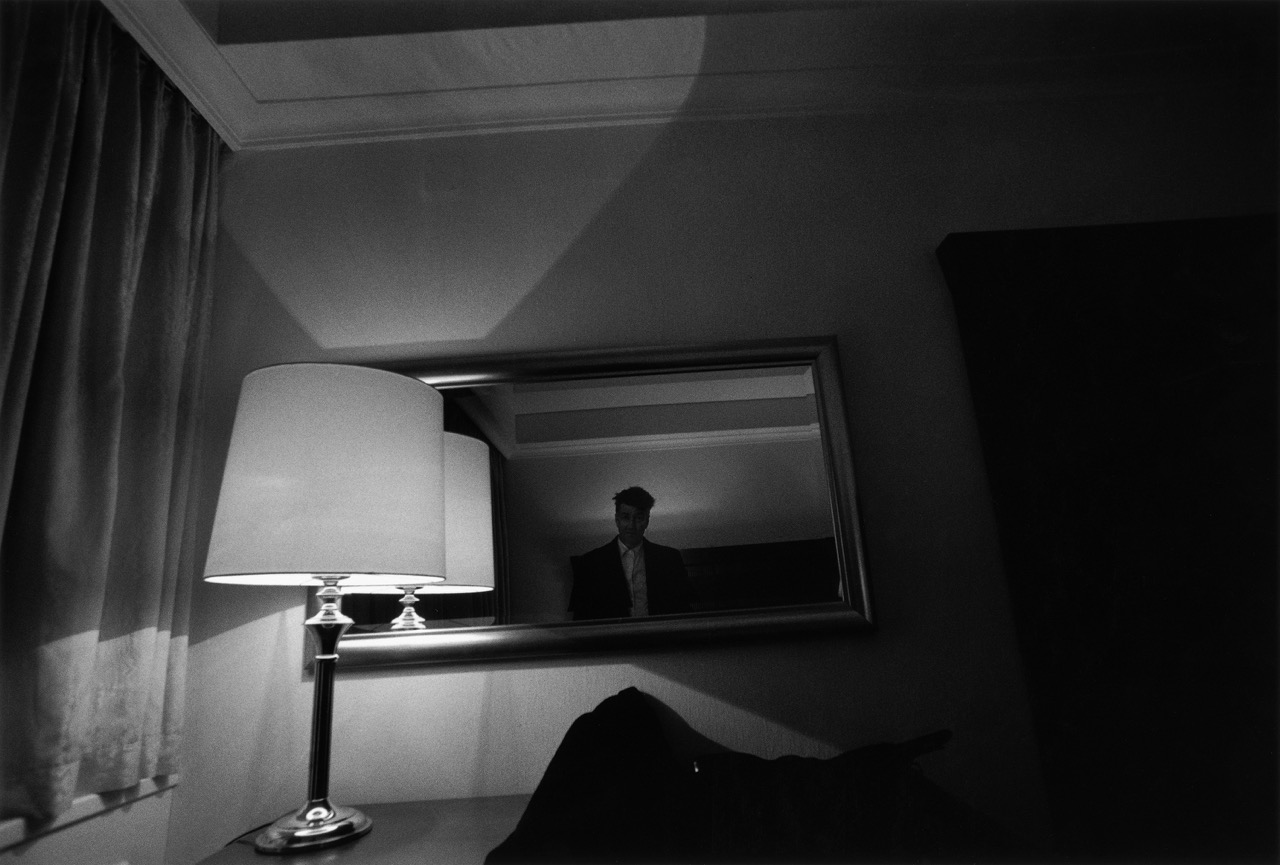

Portrait of David Lynch. Photograph by Mark Berry.

The gallery’s architecture—a converted modernist 1950s petrol station approved by Lynch himself—was once a domestic space, lending the exhibition an intimate yet strange atmosphere. “The brown carpeted floor and brown moulding invite a more inhabited, domestic feel, borrowing elements from his horror web series Rabbits (2002),” Shultz notes. Self-described by Lynch as a sitcom, the series—which later appeared in the feature film Inland Empire (2006)—features three humanoid rabbits exchanging disjointed dialogue in a murky living room punctuated by canned laughter.

The eeriness continues upstairs where David’s sculptural lamps are incorporated alongside paintings, watercolours, drawings, and a rare series of black-and-white factory photographs. The lamps—made of steel, resin, plexiglass, plaster, and wood—establish Lynch’s playful tension between brightness and darkness, illuminating while simultaneously casting shadows.The black-and-white archival silver gelatin photographs, all shot in Berlin in the late 1990s with stark shadows, primarily depict abandoned factories in spectral detail. Machinery glints like fractured reflections, while smashed windows twist shadow and depth, and arrows on pressure gauges are frozen at a standstill. An empty sink marked ‘Trinkwasser’ (drinking water) lingers as a ghostly trace of vanished lives.

Some of the imagery evokes Eraserhead, David Lynch’s 1977 black-and-white film, shot on 35mm, whose grainy, high-contrast cinematography imbues the industrial landscape with a nightmarish weight. In particular, the opening shots of smokestacks and billowing smoke, accompanied by the constant, mechanical hum and hissing of the factories, the claustrophobic corridors of Henry’s apartment, and the decaying surfaces of the factory interiors resonate in Lynch’s photographs. Elsewhere, Lynch’s photographic self-portrait appears in a mirror—reminiscent of a hotel room—the lamp glowing softly in the foreground as he slowly fades into shadow, linking the cinematic rigor of the industrial scenes to the sculptural lamps, on display, whose light casts across the photoseries. In line with Tankstelle’s architecture, these sculptures carry a modernist Bauhaus aesthetic and, unlike his other artwork, appear in stark primary colours. An erect lamp, Match-stick (2019), depicts a mechanism holding a lit larger-than-life match, reflecting his play on language, irony, and ongoing fascination with fire.

As Griffin observes, “each work evokes a very unique world, where mark-making, composition, imagery, language and text come together in a way that is unlike a lot of Western art, and untethered to what was occurring in a white cube gallery or museum at the time—he was out in the universe, if you will, with his ideas.” At Tankstelle, this expansive vision coalesces into a Gesamtkunstwerk, what Devitt Day refers to as a “kind of bleeding between all creative endeavours,” where fragments of narrative, recurring motifs, and diverse mediums intertwine, with no resolution in sight. Across a carefully curated selection of paintings, watercolours, sculpture, photography, and an early short film, the exhibition encapsulates Lynch’s artistic oeuvre of over 60 years, offering a rare glimpse into the evolution of his singular artistic vision—in time for Pace’s monumental solo exhibition in Lynch’s hometown Los Angeles this fall.

‘David Lynch’ is on show at Pace Gallery in Berlin from 29th January – 29th March