At Thaddaeus Ropac, Lydia R. Figes meets the rising artist whose dreamlike canvases are informed by the heady rhythms of dance and nightclubs.

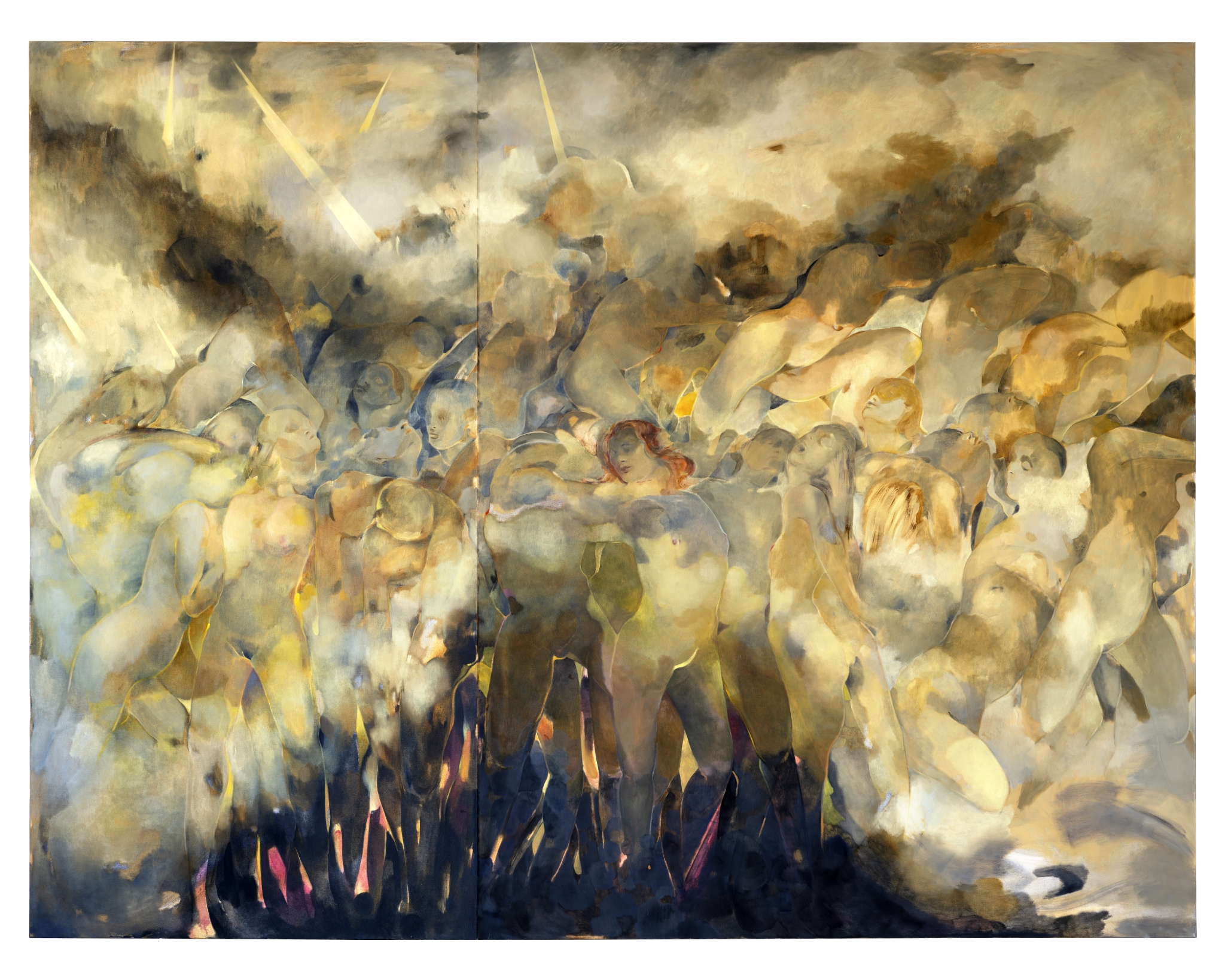

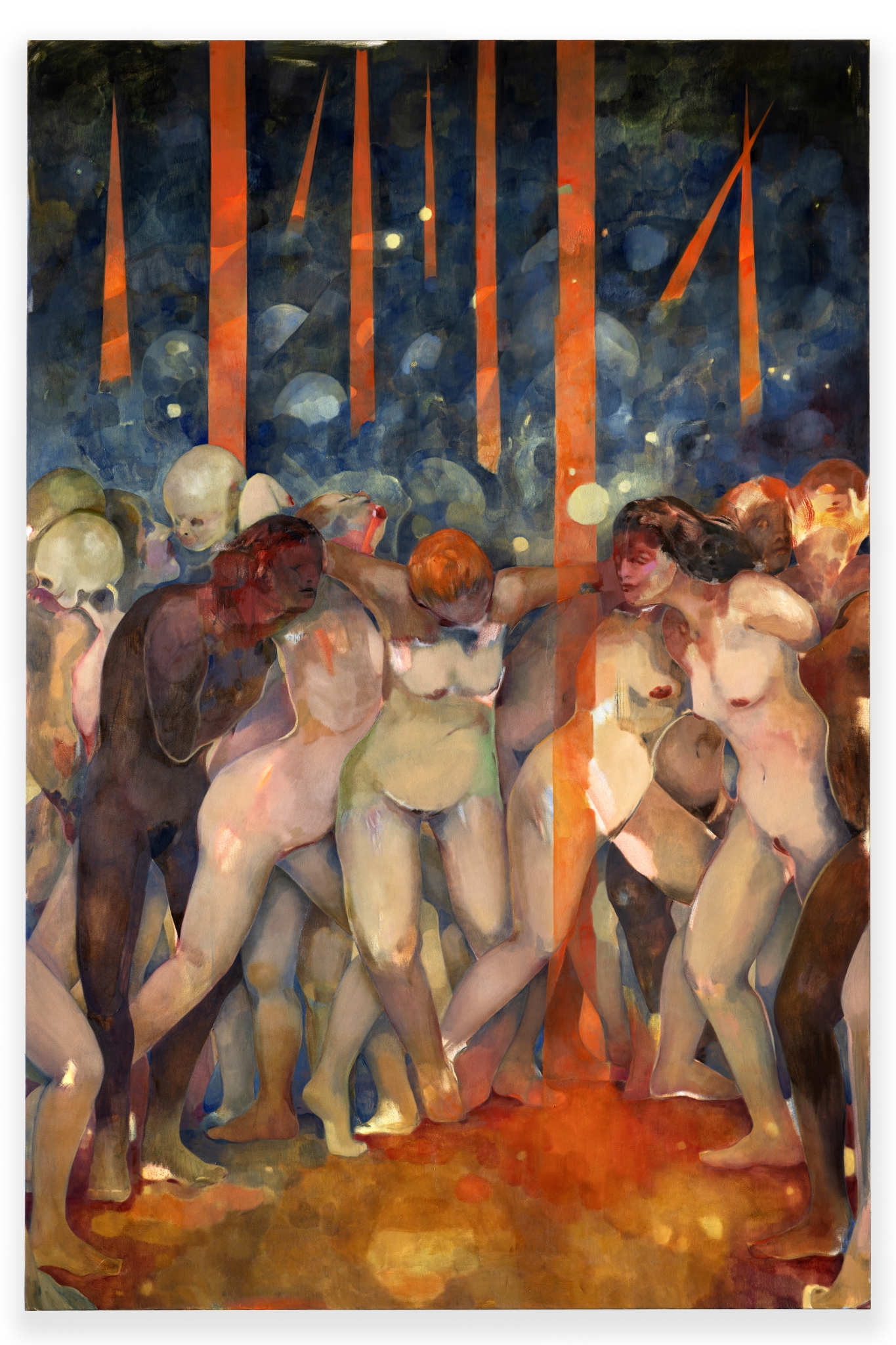

A golden haze, sweat and smoke, the vibrations of pulsating music, and the flickering of a distant strobe light—the sensuous paintings of Eva Helene Pade allude to the heady atmosphere of a nightclub. Relishing in primal, earthly pleasures, her large-scale paintings also point to something mythical; unfolding human narratives existing at the liminal threshold of fantasy and reality. These works are intoxicating dreamscapes that defy categorisation.

When I meet Pade in person, a 28-year-old Danish painter who now resides in Paris, I start to comprehend how such an early career artist has created an impressively mature body of work. As we walk through the galleries of Thaddaeus Ropac, where she is debuting her first UK solo show, Eva Helene Pade: Søgelys, she is calmly confident and, wearing leather trousers with tousled blonde hair, gives off an air of understated cool. Training at the The Danish Royal Academy of Fine Arts and graduating from her MFA in 2024, Pade is now one of the youngest artists to be represented by Thaddaeus Ropac. But don’t be fooled by her short CV. The reason I say Pade is mature for her age is because she doesn’t overcompensate when explaining her practice. She also reveals a humility you often (ironically) only find in more seasoned artists; she acknowledges that she is both creator and vessel for the final work. “I start with an idea, then I have to give it space to take its own life” Pade tells me. “You can’t really predict how the work will turn out. You can’t expect too much of your idea. At some point the painting takes over—you have to continue without knowing exactly how it will unfold. Painting is a magical process of letting go.”

Pade’s works have captured the art world’s attention since her institutional solo show earlier this year: ‘Forårsofret (The Rite of Spring)’ at ARKEN Museum of Contemporary Art, outside of Copenhagen, which took as its inspiration Igor Stravinsky’s 1913 The Rite of Spring and famous dance reinterpretion by the German choreographer Pina Bausch in 1975. Continuing the visual motifs of those primordial paintings, this new body of work similarly conjures a sense of dance and dynamism in bacchanalian spirit. Rhythm and bodily movement is a key theme for Pade. For that reason, she is instrumental in the curatorial presentation. Her free-standing canvases appear in the middle of the gallery space, thus inviting viewers to ambulate around them as if they are three-dimensional sculptures or live installations. “I want viewers to move between the works, or even observe them from the back,” Pade adds. It’s akin to a theatrical staging, but her paintings aren’t merely the props; they are the spotlit protagonists. In the high-ceilinged rooms of Thaddaeus Ropac gallery on Mayfair’s Dover Street, her figurative paintings charge the space with an electric quality.

While painting in her Montmartre studio, filled floor to ceiling with her canvases, Pade regularly plays classical music. As aforementioned, she has a particular affinity for the Russian composers: Stravinsky and Shostakovich. In the early stages of a painting, listening to music without lyrics is particularly important to her process; when the composition still exists as an elusive, abstract idea. “I channel that music into a charged, emotional space” she adds. “Later I’ll listen to whatever gives me energy, or keeps me awake. 80s Techno, Patti Smith, the Smiths.”

Eva Helene Pade. Credit: Petra Kleis

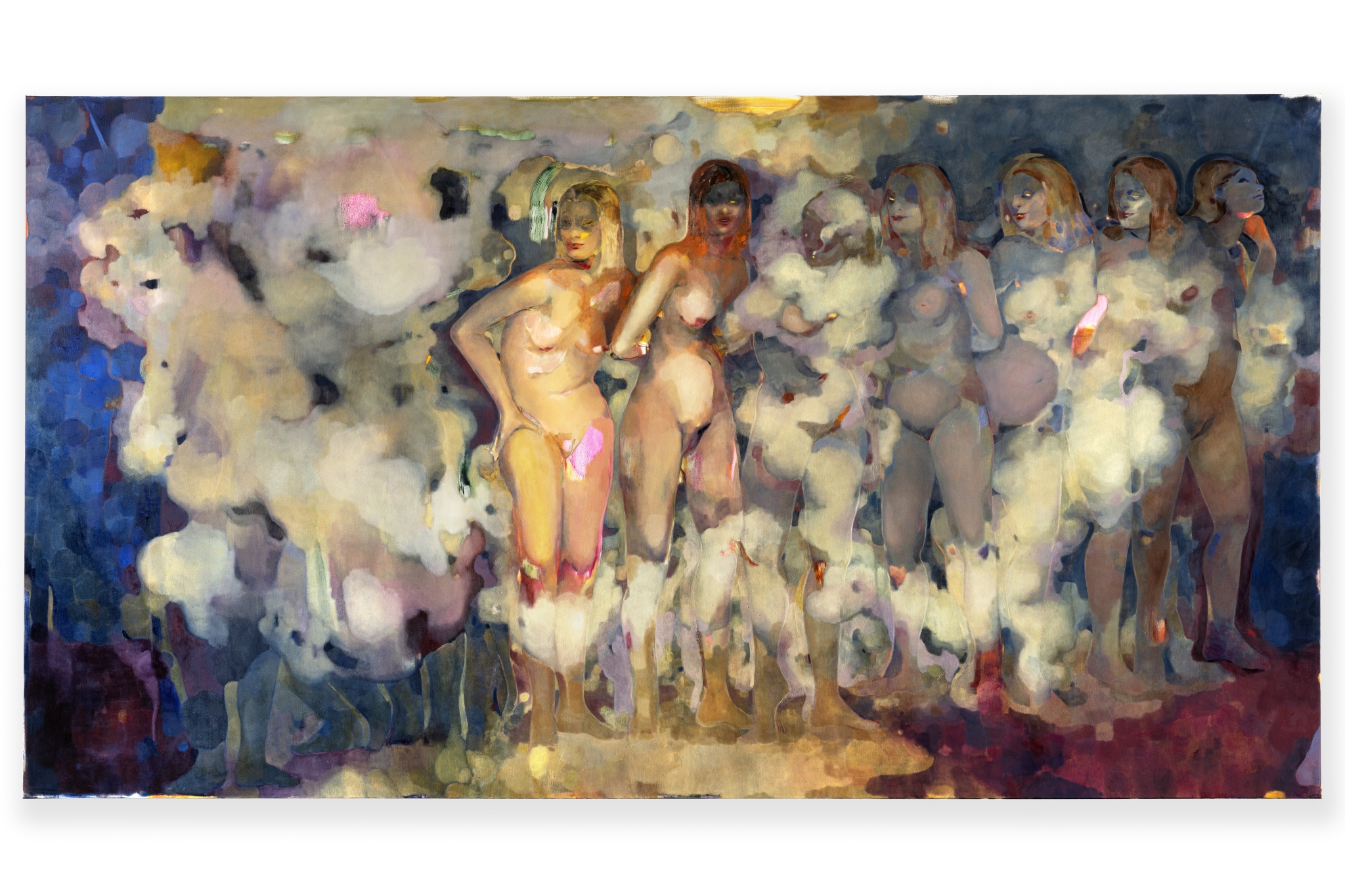

Since the ARKEN show, The Rite of Spring has continued to play on Pade’s creative imagination. The rhythmic complexity of the composition—erratic and unpredictable (there are famously 444 time signature changes in the score)—lended itself perfectly for Bausch’s modern choreography, all of which emphasised primal and even irrational human emotion, on a stage famously covered with soil and dirt. This summer Pade travelled to Bausch’s legendary Tanztheater rehearsal space in Wuppertal (outside of Düsseldorf), to meet the dancer Julie Shanahan, who worked with Bausch in 2009 before her death and and continues to restage Bausch’s repertoire, including The Rite of Spring. Half a century later, Pade’s canvases can be read as a kind of reinterpretation of Bausch. “I’m playing with the possibilities of meaning – the loaded nature of painting female figures in a line together.”

Like Bausch’s dance compositions, Pade’s paintings don’t strive for perfection or conventional beauty. Instead, raw female power is expressed in full force. If Bausch’s dancers contort and twist in disquieting, seemingly uninhibited movements, Pade’s fictional female figures shapeshift and collide with one another on the surfaces of her canvases. In stylistic parallels, Pade deliberately leaves her canvases unvarnished and unpolished—they have a matte textural quality that accentuates a certain immediacy. “I need to step back and let the paintings breathe. Otherwise the surface will become too overworked and dense” she explains.

While Pade’s figures emanate self-possession, we also detect vulnerability and looming physical threat—perhaps not so far removed from the real experiences of young women in nightclubs. Compositionally, Pade explains that she found inspiration in Édouard Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian for the work På række (In line). But we are also reminded of Manet’s paintings of modern, urban, Parisian life, Bar at the Folies-Bergère, Henri Toulous-Lautrec’s garishly illuminated women in At the Moulin Rouge c.1890s, or Edgar Degas’ textural Three Dancers in Yellow Skirts, c.1891. She’s inadvertently tracing an art history centered on venues of hedonism and places of freewheeling, bodily abandon, albeit with a more sinister, fantastical edge. A more contemporary reference might be the sensual nightclub scenes of American painter Doron Langberg.

Knækkede stråler (Broken rays) © Eva Helene Pade. Photo: Pierre Tanguy. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery

“I need to step back and let the paintings breathe.”

Eva Helene Pade

The Thaddaeus Ropac show is aptly titled Søgelys, a Danish word which loosely translates into ‘searchlight’. “I knew I wanted to continue working with the theme of smoke and light, or strobe lights” says Pade. “Søgelys has many connotations and a poetic quality. It can mean a light from a flash light, but it can also mean a search light in the sky when looking for airplanes, or looking for people running away, or the strobe lights of a club. It communicates the beauty of searching for something.”

Inside the solitude of her studio, Pade experiments with the illumination or spotlighting of her figures playing with the metaphorical potentials of Søgelys. But outside in the real world, she is increasingly under the real spotlight. I ask her how it feels to be considered a rising ‘art star’, especially as she is still in the early stages of searching creatively. “It feels incredibly strange,” she says, laughing a little at my question. “Although it sounds lovely. It’s just not my day to day life. I’m usually hanging out in my studio every day, talking to myself, or listening to records.”

Whatever emotions or vibrations Pade channels into her work, they are certainly resonating and reverberating loudly with her audience, increasingly on an international scale rather than in her native Denmark. “I’m a very active person, I hate sitting still” she confesses. For that reason, Paris has become her artistic refuge. “The city fits my mood. It’s full of life and gives me joie de vivre. In some ways that’s dangerous—but it’s where I feel at home.”