At a monastery in the Tuscan hills, the British sculptor takes her place in the universe.

The Convento di Santa Croce, a former monastery in the hills above Batignano, a small town in southern Tuscany, was constructed in the shape of a cross. When asleep, the Augustine friars who each occupied a small room along the length and width of the first floor, formed the same shape in unison. With their feet pointed to the walls and their faces to the sky, together they would have made a collective crucifix, earthbound but celestial, flying slowly through space with the rotations of the earth.

It is here that the British sculptor Emily Young lives and works, and where I have come to speak to her, staying myself in one of the monastic bedrooms. With photographer Issy Carr in tow, we are picked up in sweltering heat from Grosseto train station a short drive away. I had been to see Comparative Stillness, Young’s show at Richard Green, one of her Mayfair galleries, the day before. Each sculpture has the exact age of its stone detailed on the exhibition label: “Onyx/Over the last 2.6 million years/Persia”; “Green dolomitic stone/At least 100 million years old/Northern Italy”; “Porphyry/500-600 million years/Egypt.” While these dizzying numbers make the paintings they are displayed against seem like infants in comparison, talking to her in her garden on arrival, Young points out, with a thrum of cicadas in the background, that the Earth itself is 4.5 billion years old. The lives of these stones are only small incidents in a much longer geological history. To get in touch with the full extent of our planet’s age is much rarer. “We find stones in Scotland that are 3.3 billion years old, and also some in Australia,” Young notes, with a serene smile.

Emily Young, Rouge de Vitrolles Head, 2011, Rouge de Vitrolles. Height 90cm. Photography by Issy Carr.

For Young, sculpture is a way to interrogate our relationship with the planet. The next day, among birdsong (from housemartins, among other birds) and the occasional company of her large white dog and three cats (Bad Phil, Skinny Cat, and Fat Cat, respectively), the sculptor starts our tour of Santa Croce in the former church. In 1928 its roof fell in, meaning most of its vaulted arches have been replaced by a panorama of sky. Young describes how, at night, if you sit still for long enough, you can see the stars moving. “They arrive from one side, and on the other they disappear because of the turning of the planet,” says Young. “It’s deep time you are looking at. It’s such a thrill if you can get there.”

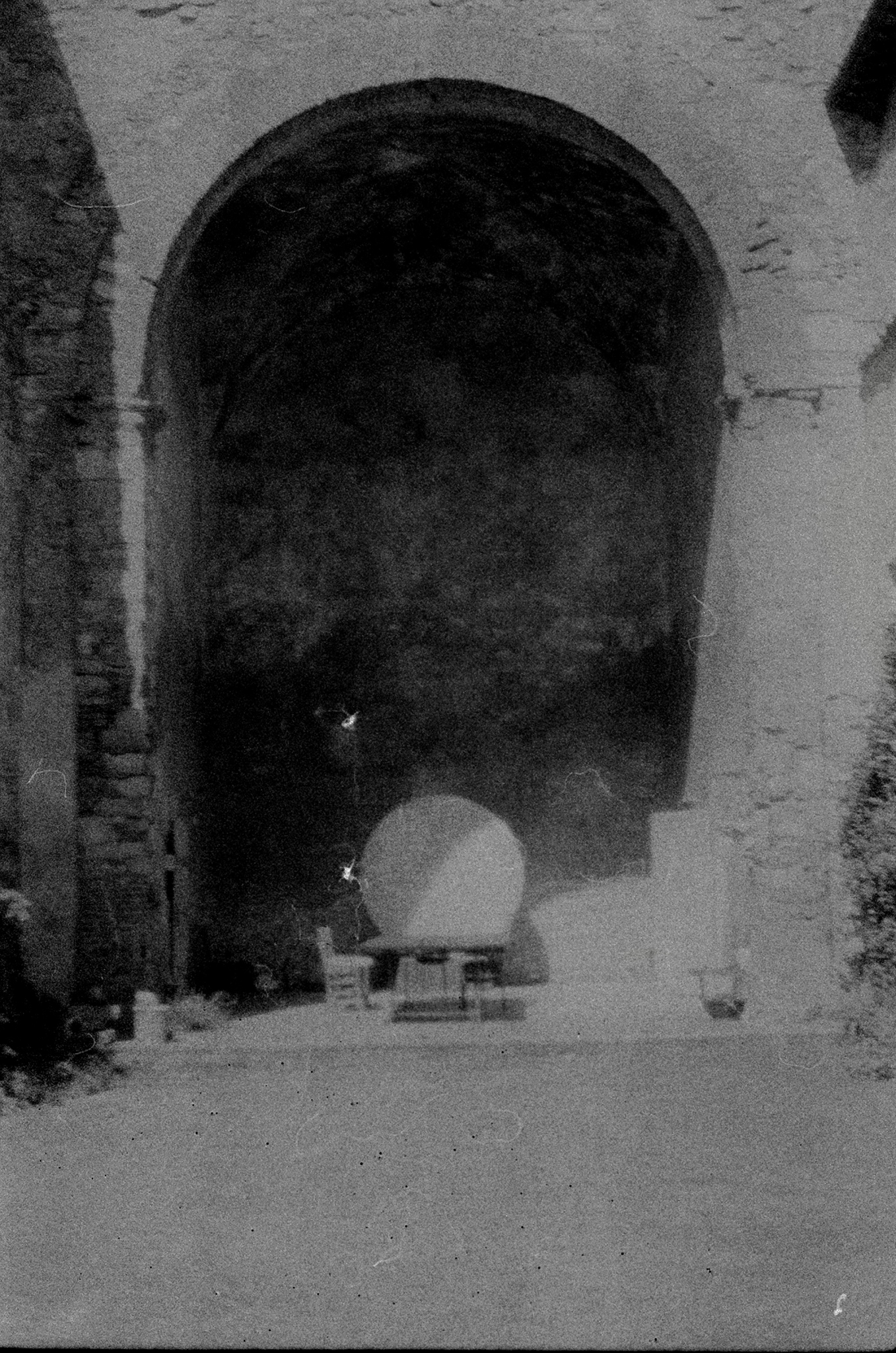

The former chapel of the Convento di Santa Croce, whose roof collapsed in 1928. The remainder of the ceiling has been painted lapis lazuli blue. Photography by Issy Carr.

Young was born in 1951 to a bohemian family and was born and grew up in Bayswater in the “Peter Pan house” where JM Barrie wrote his story of the boy who refused to grow up. Her father, the writer and politician Wayland Young, was an admirer of William Blake, the poet and artist. Blake was “open minded about nature and the beauty that the natural world can tell us about. He saw God in everything, a man of huge and unparalleled vision,” she explains. Her grandmother, Kathleen Scott, was a sculptor who worked with Auguste Rodin. She died before Young was born. “But if you’re running around, as a child, in a house filled with sculptures, and you know your grandmother made them, of course it’ll be an influence,” notes Young. After a stint at Chelsea College of Arts, and travelling widely, she worked as a painter, making large “gold and green figures in landscapes” works as well as album cover paintings for Penguin Cafe Orchestra. She turned to sculpture in her thirties. “I couldn’t do both,” says Young. “Michelangelo did, but he had a terrible time in the Sistine chapel.”

Emily Young, Tear, 2006, Onyx. Height 135cm. Photography by Issy Carr.

Although she moved permanently to Italy 15 years ago, Young had been coming to Santa Croce since the 1960s, having lived in Rome in the early 1950s with her family. The artist recalls how, as a child, she watched a wild tortoise scuttle across the garden path at the front of the house. She is happy to help me understand the full layers of the building’s history, handing me a pamphlet that gives a potted history. Closed down as a monastery by Napoleon in 1805, it became a glass plate factory run by an aristocratic French family until the 1850s. It was then used as a farm for many years, until the Second World War when refugees from the city of Grosseto took up residence. In the 1950s and 1960s, it fell into disrepair, though still being inhabited by sheep. Today the garden contains a playground and kids’ swimming pool (for Young’s family) next to the centuries-old fish pond used by the monks for Lenten and Friday meat-free days. Two sculptures by a sculptor friend of Young’s, John Cass, sit near the edge like spectators.

Since she bought it in 2011, Young has turned Santa Croce into an artistic paradise, and a fitting mise-en-scène for her sculptures. Near what was the altar, behind a long, rustic wooden table, sits one of her sculptures, a large disc in golden onyx. As well as heads and torsos, discs are one of the three “fundamental” forms that Young’s sculptures take. “I’ve always loved the perfect circularity of the moon and the sun, and I’m very aware that they are the origins of all life on earth, of us being here now,” says Young, as I spot an actual crescent moon still visible in the 10am sky. Young’s discs are symbolic representations of planetary beings. “It’s to do with honouring the moon as a great creative force in our part of the solar system,” says Young, pointing out the translucent quality of the sculpture’s sedimentary onyx, which allows light to shine through. “I like these poetic resonances. The birds sit on it too, every now and then. They live here too.”

Emily Young, Solar Disc II, 2009. Height 196cm. Photography by Issy Carr.

A free carver, Young does not plan her sculptures per se but allows each stone to suggest what it might become. As we step into her studio, a large yard-like space filled with raw materials, cranes, tools, she explains this process—which is decidedly non-anthropocentric—further. “It’s an interesting, curious thing. I just wander around the old stone yards, or quarries, or my own hillside full of olive trees, and look and see if there’s something I feel I could work with. The feel is already there,” says Young, who largely works solo, even on enormous pieces of stone, (though she employs five people to work on bronze pieces, presentation and fulfilment in the Bridport, Dorset workshop, and two in London, at Great Western Studios.) Once she starts, she allows the natural forms and colours of the stone dictate the shape and personality of the work. “The key idea is that the stone isn’t my servant, I’m working with the stone. The poor Earth is besieged by human needs and desires. That’s the big mistake that we’re making—that we have the right to abuse the earth for our benefit,” says Young. At the far end of her workshop Young points to two larger pieces of stone intended for the Casa dei Pesci, an artistic and environmental project, which, by leaving huge stone sculptures on the Mediterranean seabed, tears illegal fishing trawler’s nets and so helps prevent overfishing. “We’ve got quite a few down there now and it’s working,” says Young. “The fish are back. The seagrass is back. Even the dolphins are back.”

We continue our tour in the sculpture garden to the east, where she points out the silhouette of Monte Amiata, an extinct volcano, in the distance. In the centre is another disc, marbled grey and gold “that looks quite like Jupiter,” says Young. Just behind it, an older atypical sculpture is based on a 3D scan of a tiny piece of coral Young found decades ago on a beach. At a larger scale, it is like a deep-sea creature, but Young sees its beauty: describing a “ballerina’s foot” and “a boot” at either end of its “beautiful arch”. To the west of the house, she points out, is the Tuscan coast.

The rest of the garden is filled with Young’s stone heads. Their simple, classically inspired faces are suggestive of ancient cultures, Etruscan, Cycladic, Ancient Greek, Buddhist and—to my eyes—even Japanese ukiy-o art, and with areas of untouched raw stone, also like ruins. Their eyes are closed. Asleep? I wonder. “I’m talking about another dimension of consciousness. The stone doesn’t have eyes, but I believe it does have a consciousness. Scientists are finding that a fundamental part of physics is that there is a consciousness that manifests in a variety of ways. They’re actually the opposite of asleep. They are super awake. But it’s like experiencing the interior,” says Young, who later cites Donald Hoffman, the neuroscientist and physicist author of Visual Intelligence: How We Create What We See (1998), as an influence, as well as Federico Faggin on panpsychism. “The thought is that all of this that we see and experience around us can be described as a projection, we construct it in our brains. We construct what we see. While we are also created. We construct what we are. All the entities and the changingness of it all. Consciousness.”

Photography by Issy Carr.

In her exhibition, nearly all her stone carved heads were fe- male, while in her sculpture garden she finds space for her more masculine heads. “The gallery likes softer things,” jokes Young. “Bruisers, as I call the warrior heads—I see them as warrior poets. One is in the V&A. He’s a bit of a fighter, but he’s also a poet. I was thinking a lot about warriors in history, fighting till the death to protect the women and the children. They would have really fought tooth and nail, brutal, but then, when the battle is over, the “victors will sit upon the ground, and tell sad stories of the death of kings,” (Shakespeare, Richard II) where the ethos of the mourning song, for people who were brave warriors and died are remembered in so many of the great ancient stories. That’s a very potent idea for me, touching on sacrifice and survival, a strong part of our consciousness.”

Influenced by Blake, Young describes some of her sculptures, which have been shown in religious buildings such as Salisbury Cathedral, as “angels”. “Sometimes people look at them and start to weep,” says Young. “The look on their faces is so quiet, so still and accepting of grief and sorrow. Non-judgemental.” She describes the word “angel” as originally meaning a messenger from the heavens “just something that comes from somewhere else, possibly the heavens, … an angel can bring a new way of looking at things.” She muses that Jeff Bezos, who, on the first night of his recent wedding in Venice, which took place in the cloister of the Madonna dell’Orto, was in the company of her sculpture, a large cream coloured onyx head of a woman, and might have been changed by the experience—or at least tempted to buy one. “I’m still waiting for his call,” she jokes.

Corridors of the Convento di Santa Croce, where Augustine friars once lived. Photography by Issy Carr.

The final part of my tour around Young’s home is the cloister. With a cistern, fed by rainwater, at its centre, it would have once been the heart of monastic life, and is today filled with sculptures. She points out to the gardener a tiny cloud in the sky that might offer us some respite from the sun. We pause by Young’s sculptures—a large, pear-shaped tear that is reminiscent of something between a female body and a fossil. Torsos—the form reduced to basic elements—are the third fundamental in Young’s oeuvre. “I’m interested in stripping down to the essential,” says Young. While her discs are about connection with deep space, and her heads are about global consciousness, her torsos, she explains, motion- ing to her own stomach, are rooted in a more mortal sense of corporeality. “They’re about protection and power. There’s a beautiful, vulnerable sensibility around the front of the body. You can feel it gently humming, very quietly inside you. Then gradually, it becomes quite a magnificent state to be in, and you can feel quite strong.”

In such a sacred setting, it is hard not to wonder if for Young, sculpting is an act of faith. “It’s an act of enthusiastic curiosity,” she corrects me. “Sometimes you’re working with a stone and it’s not work- ing quickly, but there’s always something—stone is not going to let you down, it is always a stone. They’re all manifesting time in different ways, with histories that as a geologist I would be able to read, but I’m not a very good one: but suddenly I can find a bit that is a completely different colour, or texture, a break, showing itself as a piece of matter, created over aeons; maybe it was created in a volcanic explosion, and now millions, possibly billions, of years later, I’ve got this little piece of time in my hand.”