Photographer Akila Berjaoui’s images transport us to beaches across the globe, where nostalgia and sensuality collide. From the Côte d’Azur to the Gold Coast, she captures the fleeting beauty of summer, a world where glamour lingers in the salt air and the sea is both subject and muse.

Akila Berjaoui holds up a photograph of a scene at the beach: a brunette woman in a pomegranate-pink bikini is sitting leisurely on a matching towel draped over a bed of white pebbles. Her eyebrows are turned inwards towards her nose, her lips are coiled into a wavy pout, her eyes are deeply focused on something, or someone, or somewhere, in the distance, out of frame. The straps of her bandeau are undone and tucked under her arms, and her right hand is affectionately curled around the knee of a faceless man resting beside her. Berjaoui has called this image What Dreams Are Made Of.

“Doesn’t that look like Brigitte Bardot?” the photographer asks with a warm smile, calling me from her home in Paris. It’s true. This particular photo, of our Bardot doppelganger, looks like it had been captured sometime in the 50s. The tone of the image is warm, the grain slight but textured, the face of the unnamed woman wordlessly glamorous—the kind of undefinable glamour that the stars of the French New Wave, like Bardot, embodied with a mere glance or turn of the cheek. “I took that shot in Capri, Italy, about nine years ago,” she says. “It was 2016.” It’s natural, Berjaoui tells me, for some photographers to feel stylistically stuck in the eras in which they were born—an ironic phenomenon, considering the great mission of the camera has always been to capture the present as it stands. “Peter Limberg’s photos look like they’re from the 30s and 40s. They were mainly taken in the 80s, 90s, and early 2000s, but they look like Old Hollywood photos.”

Everybody’s beautiful. And it doesn’t matter what size you are or what your upbringing is like…we’re so focused on the external. I know I, too, am focusing on the external, but I’m trying to access the beauty of something deeper.”

Akila Berjaoui

Berjaoui has been around beaches her whole life. Born in Queensland, Australia to a third-generation Australian mother and Lebanese-born-and-bred father, at a young age she and her family moved to Beirut, where she spent her early childhood by the Mediterranean Sea. At seven, her family was displaced by Israel and they were forced to return to Australia, where she began to familiarise herself with the bordering oceans. “My work both reflects my Australian childhood, which was by the ocean, and my love for the Mediterranean in Beirut. Those were my early years, and both places are so hot so I spent a lot of time by the water.”

There are stars in Berjaoui’s eyes as she describes her teenage years spent visiting the beaches in Australia, recalling dazzling beauty contests on the sand where beautiful women would strut down makeshift runways in kitten heels and vintage bikinis in the hopes of being crowned Miss Gold Coast. She points me to the work of late photographer Rennie Ellis who, from the 60s through to the 90s, captured the pulsing heart of Australia’s beaches in all its enigmatic subtlety as no one else could. His influence on Berjaoui’s style is undeniable. “That’s the Australia that I remember,” she says. “The pre-Kardashian era. We weren’t so influenced by America at that point. I just remember it being so pure and so… it was so quintessentially Australian. It’s not like that any more. I think we’re so homogenised. We’re all listening to the same music, wearing the same clothes. Those are the bygone eras to me.”

Berjaoui’s nostalgia for the noweroded culture of her upbringing besides the sea perhaps explains why so many of her images feel lost in time. Her travels have taken her from the golden sands of her home country Australia to the secluded shores of Greece, the sweeping coastlines of Costa Rica, and the buzzing beach communities of the Amalfi Coast. Despite the sheer variety of location and culture, an ageless glamour blazes through the heart of her work. Like Ellis, Berjaoui has an eye for rawness, and she chooses her beaches with an undeniable, eternal honesty in mind. Nowhere is this sensibility expressed with more conviction than her photographs taken in the French Riviera, collected (along with other locations) in her popular photobook The Last Days of Summer (2017). Taken during summers in the Côte d’Azur, and Paloma Beach, the images salute a culture where going to the beach isn’t just a throwaway pastime, but a way of life. Unlike a photographer like Martin Parr, an expert in seeking out the visceral chaos and absurdity of communal beach-life, Berjaoui finds sensuality in the overlapping of sweaty, perfectly imperfect bodies strewn between endless rows of plastic sunbeds and carousel umbrellas. “Everybody’s beautiful,” she says, sincerely. “And it doesn’t matter what size you are or what your background is, or what your upbringing is like… Oh, God, I feel like I’m about to cry [laughs].” A few small beads well up in her eyes, and she adds, “We’re so focused on the external, and I know I, too, am focusing on the external, but I’m trying to access the beauty of something deeper.”

“Sometimes the scenes that I capture, admittedly, are of a hedonistic nature. The people I photograph are engaged in the pursuit of pleasure.”

Akila Berjaoui

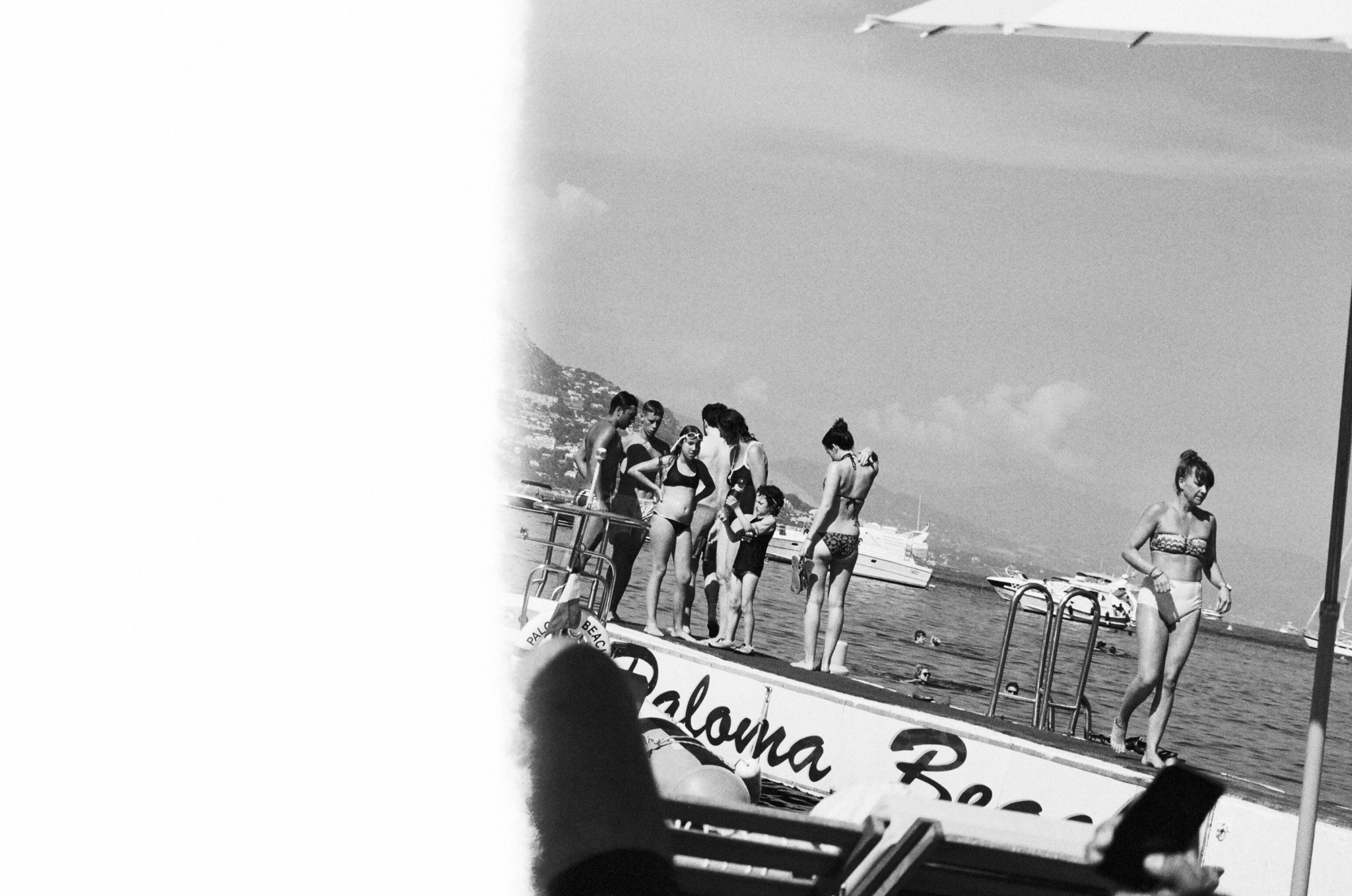

Bodies are often the focus of Berjaoui’s lens, but every now and then the eyes of the subject will meet hers at the very moment that she releases the shutter. She shows me one of her favourites from the Riviera collection, in which a striking young woman—blonde and sunkissed with dark mascara sea-smudged under her eyes—locks her gaze with Berjaoui after a puff of her cigarette, gold bracelets hanging elegantly from her wrist. Though most of Berjaoui’s images are of strangers, the subject of this particular photo is a friend. “Sometimes the scenes that I capture, admittedly, are of a hedonistic nature. The people I photograph are engaged in the pursuit of pleasure. They’re essentially self indulgent. I like to capture the beauty in that. There’s so much ugliness in this world that I prefer to focus on the positives that life has to offer.” She shows me a black-and-white shot of a family playing on a jetty on Paloma Beach, grainy and half exposed, incomplete, like a memory torn violently from the fabric of time. “I love imperfections in life and in photography,” she says. “I love that half of the image is missing—some people might not appreciate it, but I value that.” The shot, unlike any other in Berjaoui’s selection, perfectly expresses the temporality of the photographic medium, as well as how it relates to Berjaoui’s artistic struggle with nostalgia. It suggests a deep-rooted love affair between the photographer and the beaches living in her frame, complex and conflictual— Berjaoui’s film cameras, she explains, only last a summer at a time, with the sea salt itself seeping into the body of the gadget and eroding it from the inside.

I love imperfections in life and in photography. I love that half of the image is missing—some people might not appreciate it. But I value that.”

Akila Berjaoui

Paloma Beach, Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, France, 2016. By Akila Berjaoui.

“It’s definitely voyeuristic,” Berjaoui says of her images, more aware than anyone that photography is, by design, a craft built on the act of observation. Still, the photographer perhaps doesn’t give herself enough credit for the kinship with which she shoots her women, whom she refers to once or twice during our conversation as her “collaborators”. She describes one of the proudest shots she’s ever taken, around 13 years ago, of a young girl sitting alone at a beach in Positano, on the Amalfi Coast, and crying. “She was sitting there, her arms around her legs, teary eyed, looking out into the water. She was so beautiful at that moment. I wanted to go over and hug her… but I took a picture of her instead. I didn’t want to interrupt her or this beautiful, painful moment she was experiencing. Maybe there’s an element of exploitation in that. But it felt right to capture that.”

Berjaoui’s next photo book is inspired by a quiet summer she spent in Greece during Covid, The upcoming collection swaps out the crowded beaches of the Riviera with more secluded sands, and the hedonistic, communal beach culture of her most popular work with, now, a singular muse. “My photography reflects my mood and state of mind, pre- and-post-Covid for example, major shifts in the collective spirit and the world stage. In the past five years I’ve focused less on, collectively, people at beaches, but the individual I’m shooting in natural beach environments, focusing more on that idea of returning to nature.” Though she confesses that venturing this far from the style that launched her career is a risk, half joking that it’s the “busy beaches that pay the bills”, there’s certainty that even as she moves into bold new territory, the timeless sensuality and sincerity in Berjaoui’s work will remain unshakably inherent. Trying to make sense of her own artistic intentions, she confirms as much. “It’s intuitive,” she says, deep in thought. “It’s about how you feel it rather than how you see it. But the question I constantly ask myself is: what is the common thread in humanity, whatever the race, age, or gender? What I’ve seen in Brazil, the Mediterranean, Australia, South Africa, Beirut, Egypt, and more is a celebration of life and love—a throughline of humanity being brought together by the sun and the sea.”