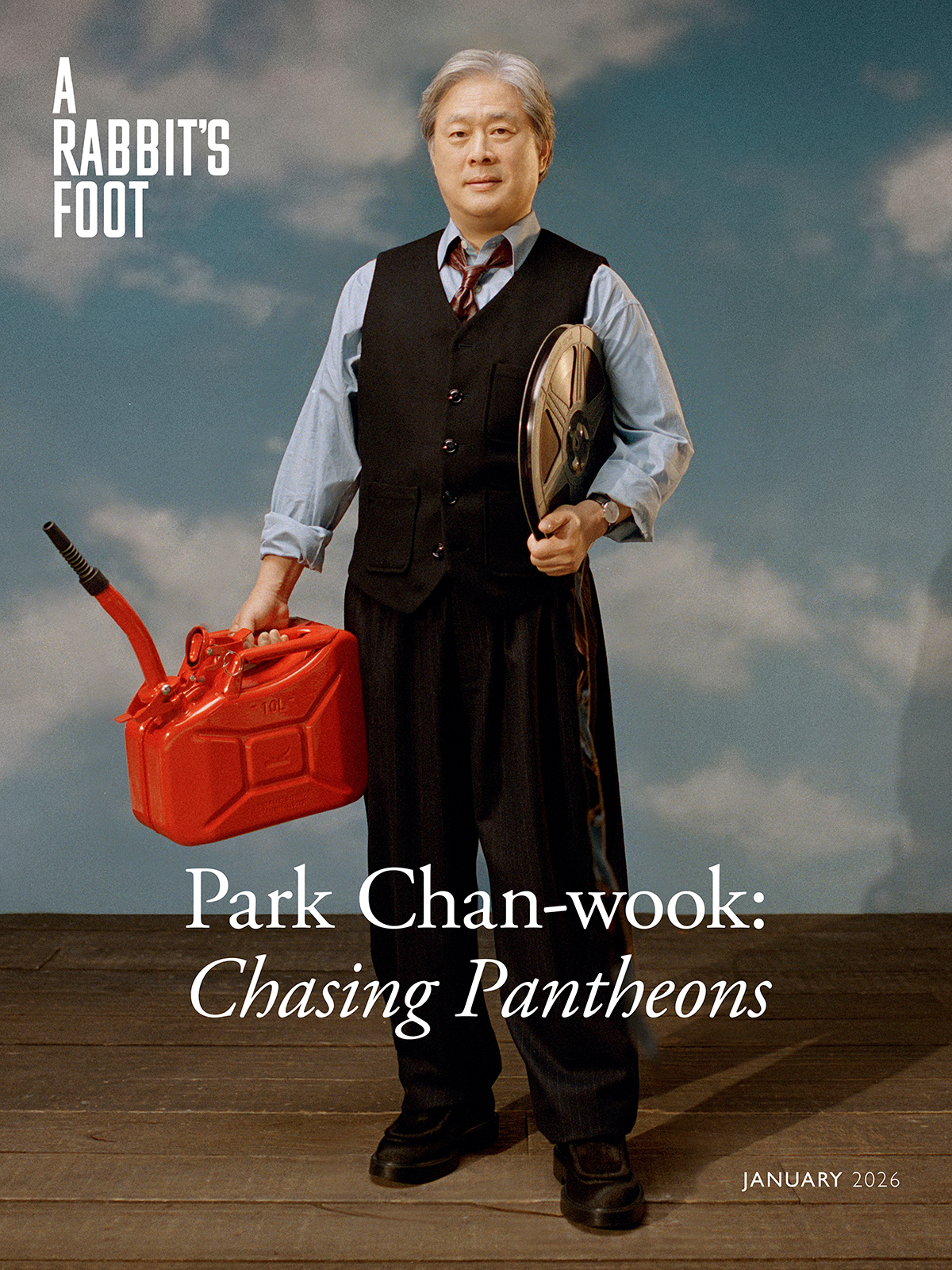

For our January digital cover story, we sat down with the South Korean auteur to discuss the crossroads of love and torture, the singular theme that runs through his work, and reaching the pantheon of the masters with his latest feature No Other Choice.

You can also read this feature—newly translated in director Park’s native Korean—here.

Over the past 30 years, he’s developed a reputation as one of contemporary cinema’s most enduring visionaries, but the prospect of legacy still casts a heavy shadow over South Korean filmmaker Park Chan-wook.

We’re discussing pantheons. In 2016, Park had said in an interview with Film Comment that only a few filmmakers in each generation rise to the level of the greats. The likes of Alfred Hitchcock, Mikio Naruse, and Kim Ki-young—in Park’s eyes, giants and heroes of cinematic history. Many cinephiles would take no longer than a heartbeat to nominate the South Korean auteur, famed for films such as Oldboy (2003) and The Handmaiden (2016), among them. Park, however, has doubts. “With every film, I put everything into reaching the level that they were at,” he admits, staring out the window of our London studio, which overlooks a foggy, sun-hazed cemetery (an image that could have been ripped straight out of Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958)). “I also experience true devastation at the realisation that I’m not quite there yet.”

On set, he’s Director Park, a title his cast and crew use with reverence. The name suits him. In person, he carries himself with the assuredness of a man who’s spent half a lifetime deciding what belongs in the frame and what doesn’t. Throughout our conversation—taking place in London, where the virtuosic director is here to promote his razor sharp black-comedy No Other Choice (2025)—maintains a cool poker face, occasionally allowing himself a soft chuckle or a long, meditative hum when taking the time to think over a question.

Park’s work has long been a lightning rod for debate, with conversations about his filmography often—misleadingly—being boiled solely down to his trademark blend of violence and comedy. It’s true that his films are studded with moments of darkly comic brutality: in Oldboy, a man’s teeth are wrenched out with the peen of a rusty hammer; in Sympathy for Mr Vengeance (2002), a child is abducted and accidentally killed by her kidnappers; in his latest, a lifeless body is coldly treated like processed meat and buried in a suburban backyard. But make no mistake: every ounce of pain inflicted in a Park Chan-wook movie is part of the director’s meticulous design. These are shocking images, yes, but not empty ones—not quite bloodthirsty.

“With every film I put everything into reaching the level of the great directors of the past. I also experience true devastation at the realization that I’m not quite there yet.”

Park Chan-wook

Furthermore, embroiled in Park’s obsession with sin, fury, and vengeance is a fascination with love—not the self-satisfied, saccharine kind, but the kind that bleeds. I point out that many of his films—from the supernatural thriller Thirst (2009) and the English language Stoker (2013) to period piece The Handmaiden and the hot-blooded noir Decision To Leave (2022)—ultimately orbit the same idea: a love, familial or romantic (in the case of Oldboy—spoiler alert—both at once), that’s twisted yet inescapably human. “I’m often disappointed by people who overlook that aspect of my storytelling,” says Park.

When I ask him how he reconciles love and violence so seamlessly in his films, he likens himself to a mad scientist putting their subject under extreme torture. Indeed, an answer fitting of the man who gave us the delightfully wicked Vengeance Trilogy. “I apply all sorts of torturous perspectives in pursuit of discovering what love truly is and what it can contain,” he explains. “It’s like when you’re in a laboratory and you put a subject under extreme conditions… almost like you’re torturing them. Through these conditions, something deeper is revealed about the subject. The twisted nature of the romance in my films works to the same effect: under extreme conditions, the good and bad of humanity reveals itself.”

Park’s stoic demeanor softens when the conversation turns to family. I ask him about the influence of his daughter, for whom he made and dedicated his 2006 feature I’m a Cyborg, but That’s OK. The film, a sci-fi romance set in a mental asylum, is notably quirkier and sweeter than the others in his filmography. “As a young feminist, my daughter gives me a lot of advice on my work,” he says with a warm smile. “Only after her approval do we complete writing the script.” Later, when discussing the uproar over his groundbreaking early work, he says, “My wife doesn’t miss it. She was greatly shocked by the audience reaction to Sympathy for Mr Vengeance. And because she doesn’t miss it, I don’t miss it.”

Despite setting the bar dizzyingly high in his early career with Korean new wave landmarks Joint Security Area (2000) and the Vengeance Trilogy, No Other Choice sees the 62-year-old at the height of his craft. A whirling black comedy about the vampiric effects of modern capitalism, it stars Park alumni Lee Byung Hun (Joint Security Area) as You Man-su, a devoted family man who, after being let go from his job at a paper factory, desperately resorts to murdering his competitors for another position. “Exploration of Korean masculinity was one of the most important goals of this film,” Park says. “It portrays how pitiful men can be when trapped in structures of their own making.”

The film earned huge acclaim when it premiered at the Venice Film Festival in August, before later topping the South Korean box office. Park left Venice without a prize, and has yet to claim an Academy Award like his friend Bong Joon-ho, who dominated the 2019 Oscars with Parasite (2019). But his legacy has long transcended the pursuit of trophies awarded by, in the words of Bong himself, “local” award shows, with the work itself standing the test of time against a rapidly changing cinematic landscape, and reaching new audiences in the process. In 2024, he released his second English language TV series, The Sympathizer, which he recently described as his proudest work to date, while The Handmaiden introduced a new generation of cinephiles to his work. The period-thriller and sapphic romance, now hailed as a modern queer classic, is currently sitting at number 67 on Letterboxd’s Official Top 250 Narrative Features—a list that aggregates the highest rated films on the app (with Oldboy trailing closely behind at number 87).

Still, Park speaks about his career with the humility, and the burden, of an artist in dialogue with the greats. When he began adapting Donald E Westlake’s The Ax (1997) into No Other Choice, Park said he hoped it would be his first masterpiece. Sitting across from him now, I ask whether he thinks he achieved it…

Luke Georgiades: You first started thinking about making No Other Choice many years ago. How different would the film look if you had made it then rather than now?

Park Chan-wook: Everything would have been different. It would have been an English language movie. It would have been set in the US. The actors would have been different. It would have depended on what kind of film came before it, too. That matters a lot to me. If this film came after Thirst, it would have changed the final product. What I mean by this is that because this film came after Decision To Leave, it has the opposite characteristics—while Decision To Leave was more poetic, this is more prosaic; and while Decision To Leave was more minimalist, this is more full; and while Decision To Leave was more feminine, this is more masculine. If I had made No Other Choice in the past, it would have looked different depending on the film that came before it.

LG: You once said that only a handful of filmmakers in each generation join the pantheon of the masters. Do you aspire to be one of those filmmakers?

PCW: I still have that same respect for the great directors of the past, and with every film I put everything into reaching the level that they were at. I also experience true devastation at the realisation that I’m not quite there yet.

LG: What’s your earliest cinematic memory?

PCW: It was the film Waterloo Bridge (1940). I watched it with my mother. She had already watched it in the cinema and had liked it, so she wanted to watch it again on the TV. The film instilled some vague notions about romance in me. The first film I watched in the cinema was the Bruce Lee film Fist of Fury (1972). The characters’ rage and appetite for vengeance left a strong impression on me.

LG: There’s always been a lot of talk about the violence in your movies, but I’ve always been just as attracted to your depiction of romance. Love is everywhere throughout your filmography. It’s always a little twisted, but pure in its way. Does that come from a certain philosophy that you might have about the nature of love?

PCW: I’m grateful that you think that I’ve portrayed romantic love so consistently in my body of work, because I’m often disappointed by people who overlook that aspect of my storytelling. I apply all sorts of twisted and torturous perspectives in pursuit of discovering what love truly is and what it can contain. It’s like when you’re in a laboratory and you put a subject under extreme conditions, like extreme cold or heat, almost like you’re torturing them. Through these conditions, something deeper is revealed about the subject. The twisted nature of the romance in my films works to the same effect: under extreme conditions, the good and bad of humanity reveals itself.

LG: You made your 2006 film I’m a Cyborg, but That’s OK for your young daughter. Now that she’s older, what is her relationship like with your work?

PCW: My daughter is currently studying to be a colourist. She’s not working in the film industry, but she’s taking her first steps, so we have a lot of discussions about filmmaking and cinema. As a young feminist, my daughter gives me a lot of advice on my work, in regards to how women are portrayed in the story, or what elements women audiences might find uncomfortable. We have a lot of discussions about that. Only after her approval do we complete writing the script.

“I’m old now, I’ve lived as much as I can, but how will the rest of my daughter’s future unfold? Climate change, the development of AI, war, nuclear weapons, all these things worry me. I’m worried about the impact they’ll have on my daughter.”

Park Chan-wook

LG: You’ve portrayed quite a worrying vision of the future in No Other Choice. How does tomorrow make you feel?

PCW: It makes me think of my daughter’s future. She’s 31 years old. I’m old now, I’ve lived as much as I can, but how will the rest of my daughter’s future unfold? Climate change, the development of technology such as AI, war, nuclear weapons—all these things worry me. I’m worried about the impact they’ll have on my daughter.

LG: In the film there’s this push and pull between modernity and tradition. The men in the film fiercely stick to their old ways, absurdly so. Is this a problem you find particularly with masculinity in South Korea?

PCW: Exploration of Korean masculinity was one of the most important goals of this film. It portrays how pitiful men can be when trapped in structures of their own making. There are stronger traces of patriarchy in Korean society relative to the West, so there are certain responsibilities one must take as a husband and father, or certain ways that they must behave, and if they fail to live up to those expectations it becomes a shameful ordeal. For Man-su and Bunmo, losing their jobs is painful because those jobs are rooted in their entire purpose as men. Without them, they are fundamentally useless.

LG: Lee Byung Hun’s comedic instincts here are sharper than they’ve ever been.

PCW: What’s key, though, is that Byung Hun never played for laughs. He didn’t even realise that his character was comedic. He focused on the character’s genuine emotions. His pursuit of truth is what made his performance so funny and alive.

LG: It’s been 25 years since you both made Joint Security Area together. How has your creative relationship changed over time?

PCW: Since JSA, I have always asked Byung-hun, “When are you going to age?” I wanted him to age quickly, but he looks so young, his skin is so firm and he has such a nice, white toothy smile. He looks so healthy, which was not the appropriate look for the characters of the films I’ve made since. He has now finally reached the age where I can cast him as an actor once more. One of his nicknames in Korea is that he’s “teeth rich”—he has a smile that suggests that he has more teeth than the average person, which is, of course, absurd.

LG: When Sympathy For Mr Vengeance came out, you said that your intention was to leave the audience a little exhausted after watching the film.

PCW: I still believe in that same philosophy. When a film drives me into a state of exhaustion, I feel very satisfied. That’s because throughout the film you’re tensed up. It doesn’t need to be a horror movie to have this effect. Even an [Yasujirō] Ozu film can give you a feeling of intensity. If the film is exciting visually and orally it will require all your attention, and leave you in that same state of satisfied tiredness. That is the mark of a finely crafted film.

LG: Is there a common idea that runs through all of your films, from as early as The Moon Is… the Sun’s Dream (1992) to No Other Choice?

PCW: The consistency between all of my films is the exploration of the emotions that are born from sin. My films focus on characters who commit great sin, and the pain and confusion that arise from that place. My characters don’t ignore their own guilt. I want, always, to pose ethical dilemmas to the audience through my stories.

LG: You said in 2019 that you wanted to make this film your masterpiece. Do you think you’ve succeeded in doing so?

PCW: I had been working on the film for so long that a desire was born to make this into a so-called masterpiece. But the first condition to making a masterpiece, to quote Coppola, is to get rid of the desire to make one. So I wasn’t purposefully keeping that in mind during the making of the film—I wasn’t trying to surprise audiences with the greatness of this ‘upcoming masterpiece’. Did I achieve that goal? I don’t know. But I made a unique film that is different from my previous films. That alone brings me some satisfaction.

Park Chan-wook for A Rabbit’s Foot. London, 2026. By Fatima Khan.

Creative Director & Photographer: Fatima Khan

Words: Luke Georgiades

Korean translation (print interview): Emily Jisoo Bowles

Executive Producer: Anna Pierce

Stylist: Andrew Georgiades

Videographer and editor: Katya Ganfeld

Video Producer: Luke Georgiades

Production Coordinator: Olivia Kenney

Production Designer: Alice Jacobs

Creative/Video Assistant: Kitty Spicer

Lighting: Laurence Hills

Grooming: Anni Brønning Rademacher

Production Assistant: Isaac Ashley

Styling Assistant: Cailey Hartshorn

Translator (Park Chan-wook): Jiwon Lee

Title Treatment & Key Graphic design: Broad Peak Studio

Graphic designer (Korean translation): Claire Hyungkyung Chin

With special thanks to Skylar Kim.

Look 1: Giorgio Armani waistcoat, trousers

and shoes, Bottega Veneta leather tie, Auralee shirt,

Jessie Western hat.

Look 2: Full look by Giorgio Armani,

Jessie Western belt.