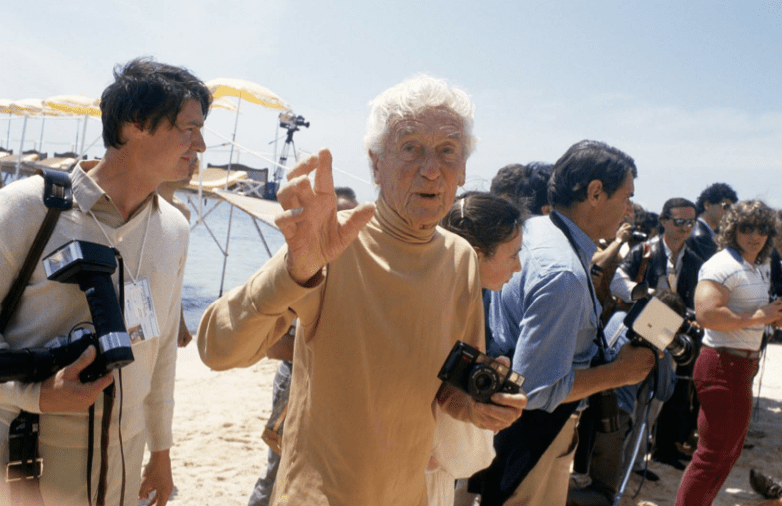

“The ultimate Peter Pan of photography.”

I have often said that if I had to choose just one photographer—if you like, my desert island photographer—it could only ever be Jacques Henri Lartigue.

As a young boy, I visited his exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris in 1977. It was the very first photography exhibition I had ever seen, and its effects have stayed with me ever since. His images estill give me more succour than almost anyone else I can think of. How can a man, who I never met, still have such a profound effect on my senses, even after all these years and after having seen more photography than I probably should have! His timeless and perfect pictures still charm and captivate me, and I can still smell and taste the sweetness of a Lartigue photograph—and what a unique flavour they have.

Lartigue (1894-1986) began his obsession with photography at the age of 8. He was alive during a period when some of the most vibrant and major cultural shifts of the early 20th century occurred, and he recorded what he saw around him in his own idiosyncratic way. Some of his most captivating early pictures are of his close family, his toys and surroundings, his nanny, his bath-time, and the fashionable ladies who would parade down the Bois du Boulogne in front of his infant eye, and they remain some of most remarkable and enduring photographs of the early 20th century, these images, all made by a ten-year-old boy.

Lartigue’s affinity with what was then new technology, the handheld camera given to him by his father, developed into a passionate and sweet addiction that would stretch over 70 years. He almost invented the lifestyle-photograph (Martin Munkacsi working for Harper’s Bazaar in New York would come some 25 years later)—and encapsulated the contemporary meaning of the expression ‘fashionably chic’. Lartigue was also the first to adopt the concept of the well honed snap-shot visual diary, or, in other words, today’s Instagram. This was absolutely his invention and part of his extraordinary legacy.

Lartigue created an album for each year of his photographic life—some 82 of his albums still exist today, held by the Donation Jacques Henri Lartigue in Paris, a governmental cultural agency who are the guardians and owners of his archives. Lartigue led a charmed life and the albums are time capsules of this life with annual migrations from Paris to the Cote d’Azur and Monte Carlo, and then to the mountains to ski in Chamonix or St Moritz and follow the ski-jorging, and then on to Biarritz and the popular Atlantic coast and finally his last home with Florette in Opio, above Cannes.

From the age of nine or ten and until 1984, Lartigue could be found glueing photographs into these albums, in multitudes of shapes and colourful tones that were available to those who wished to experiment with silver gelatin printing. He would often add small drawings and explanations as to what and where certain pictures were taken. This joyous practice endured throughout his life.

His photographs look deceptively simple, stripped of any artifice, capturing those sweet fleeting moments and preserving them forever. Through the eye and in the hands of Jacques Henri Lartigue, the common snap-shot got to the heart of photography as an art form and changed the history of photography forever. His photographs did not suffer from the pretensions and swagger of the ‘professional photographer’, and he preferred to be likened to a ‘hobbyist’ and keen amateur. Lartigue had no time for the making of his photographs, and all his work, though under his direction, was printed by a local dark-room. He sometimes chose to print his work in green or pink tones and often in sepia too. He was also an early adopter of autochrome film produced locally in France by the Lumiere Brothers on glass plates. And then later on, he enjoyed working with colour film as it became available and easy to shoot and print. He also played with stereo photography, which produced a three-dimensional photograph which had to be viewed through a special stereo viewer. It is interesting to note how not only history repeats itself, but also technology. We are heading the same way again with VR.

Lartigue is considered to be one of the true greats of the 20th century and is still hailed as one of the founders of modern photography. It is hard to imagine how that fame arrived so late for him—Lartigue was almost 70 when he was “discovered” by John Szarkowski, the then curator of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, who decided upon seeing Lartigue’s albums at a chance meeting on a train to exhibit a selection of his key early images, what was to be his first international exhibition which opened at MoMA in New York in 1963. This was the same month that John F. Kennedy was tragically assassinated. The whole of that month’s LIFE magazine was devoted to Kennedy’s legacy, all but for 8 pages, which were devoted to the work of none other than Jacques Henri Lartigue. It was one of the biggest selling editions of this famous periodical and Lartigue became famous overnight .His joyous, life enhancing snapshots were the perfect antidote to the terrible news that had swept the world, and for many, this was their first encounter with this brilliant smiling man and his life affirming images.

Lartigue had been taking these photos for decades—photos of his family and friends, of sports, early and dangerous aviation and car races, the beaches of Antibes, La Garoupe and Biarritz and during la Belle Époque. And of course, the gorgeous women who populated so much of his life—his three wives, Bibi, Coco and finally Florette, who I was fortunate enough to meet and work with on the many exhibitions we held of Lartigue’s work at our gallery in London. It appeared that Lartigue had been simply taking these photographs for himself. Who else but a supremely passionate and talented ‘amateur’ could have this kind of talent and drive without a single trace of public recognition nor success? He was a true artist who never lost that innocent and childish enthusiasm, and unshakeable optimism that is so essential in great art.

The world was Lartigue’s playground and he seemingly pointed his camera at whatever passed by him.But he instinctively knew how to not only spot those moments when people revealed themselves, but also how to tease the essence out of his subjects and he was able to pinpoint that moment again and again, with what seemed like almost no effort. Henri Cartier-Bresson often said that Lartigue sometimes understood the ‘decisive moment’ better than he did. Lartigue absolutely knew what he was doing, as he saw things other people did not see.His camera was a natural extension of his mind and was used with a simple elegance and precision. No big lenses, no fast film, and no retouching. It was all real and it was also all beautiful. Lartigue’s photographs are still a guaranteed fast-track to feeling good. The world, despite the unsettling changes happening around him, was portrayed as a perfect and beautiful place full of joy and happiness.

Just like a child who still believes in magic, Lartigue never parted from his elemental spirit of playfulness, lightness and spontaneity. It was with his penchant for capturing the essence of movement and freedom of his surroundings that made his work seem so unlike anyone else’s. There was no formality and no stiffness to his pictures and the world seemed to glide past his lens in a perfectly composed and elegant fashion. What Lartigue was able to achieve, should not have been possible with the early and somewhat limiting equipment and film that was available to him at the time. He didn’t simply capture the ‘moment’, but introduced a new radical unseen reality to this new oeuvre. Snapping his cousin leaping and frozen in in mid-air, or the sleek speed of a racing car Délage, often voted as one of the very best sport pictures ever made, and of course, the exquisite women such as the unforgettable Renee Perle, Lartigue was able to tease extraordinary ‘effects’ and emotions out of the subjects he chose to preserve on film. In his book The Invention of an Artist, Kevin Moore challenges the concept of the self taught naïve boy photographer , but this does not answer the enduring question as to how Lartigue was able to do what he did. It should not have been possible, with the cameras available, but is that not what genius is all about? To achieve the seemingly impossible?

One of his greatest fans, Richard Avedon, referred to Lartigue’s albums as a ‘ Diary of a Century’ and famously recreated an abridged version of them as a facsimile some years later. Avedon knew when to pay homage where homage was due.

So many photographers would agree that Lartigue’s charming influence is an integral part of their photographic DNA and I still see it today in some of the world’s greatest current practitioners. But even with the amazing digital tool box that photographers have today, I still prefer the honesty and simplicity of a photograph by Jacques Henri Lartigue.

The canon of 20th century photography would be poorer if Lartigue had not been discovered by John Szarkowski all those years ago. Put simply…he was the best.

Florette, by Jacques Henri Lartigue, Paris, 1944.