The Middle Eastern folktale has spawned numerous on-screen adaptations, from Michael Powell’s The Thief of Baghdad and Miguel Gomes’s Arabian Nights to Julia Jackman’s upcoming 100 Nights of Hero.

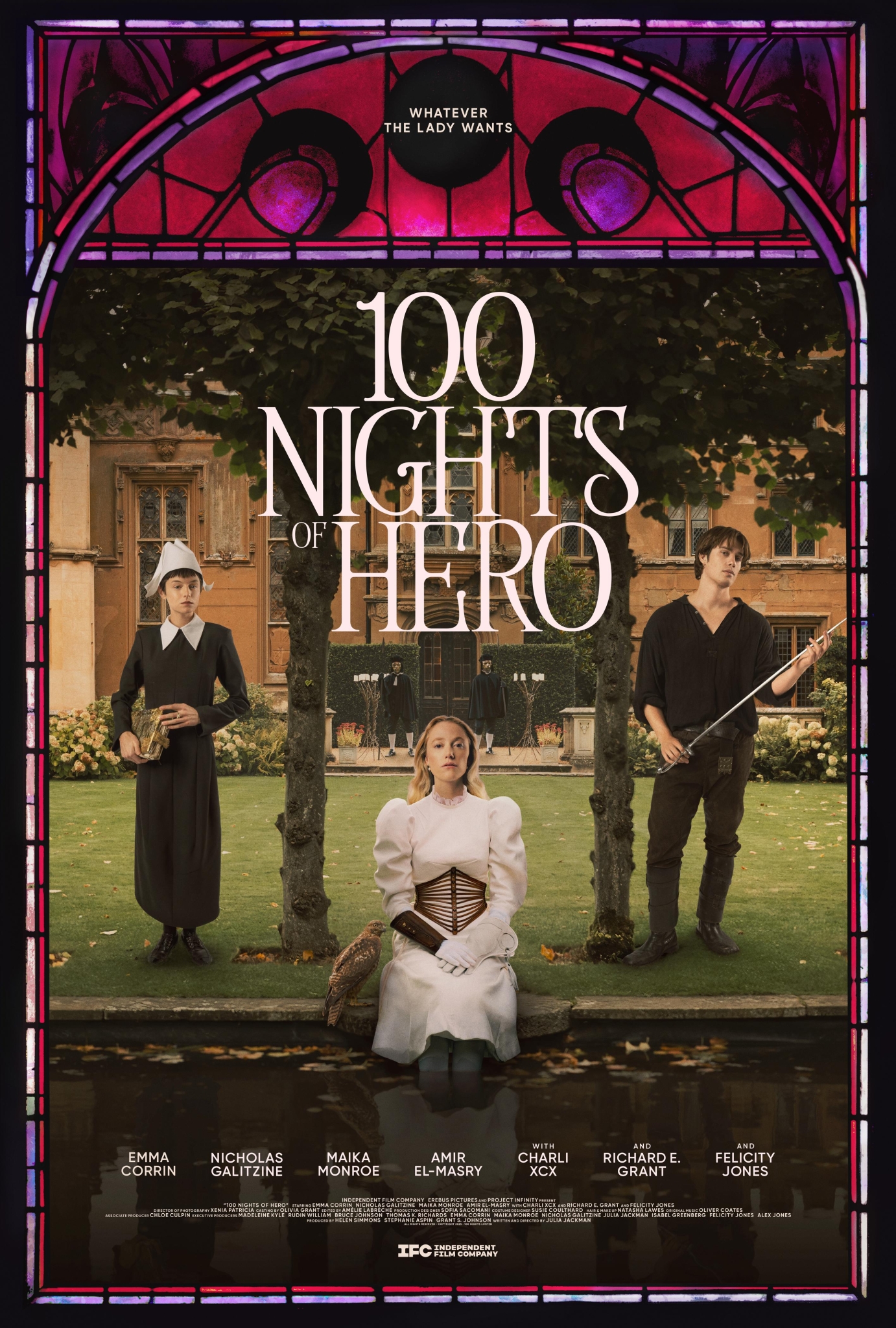

Julia Jackman’s 100 Nights of Hero is no conventional adaptation of The Arabian Nights or One Thousand and One Nights. Taking place in an alternate reality in which the grip of the patriarchy is so fierce that women are not permitted to read or write, though the intricate fantasy world of Jackman’s irreverent drama has age-old politics this is a decidedly modern reimagining.

It’s based on a graphic novel by Isabel Greenberg, which in turn loosely takes its beats from the Middle Eastern folktale One Thousand and One Nights. Except, where Scheherazade spins colourful yarns of thiefs, princes and smugglers to delay her death, Jackman’s storyteller – a cunning Emma Corrin – tells tales of female liberation.

The origins of this compendium of Arabic folktales, first emerging in the Islamic Golden Age, remain mysterious. These diverse stories by an array of authors hailing from Arabic, Persian and Mesopotamian nations contain sorcerers, sultans and genies – but are all united by the framing perspective of Sheherazade, who distracts her wicked king husband from murdering her by entertaining him with 1001 stories. Onscreen, the Arabian Nights legends are a cinematic universe unto themself, ranging from German expressionist versions to anime remakes titled Doraemon Nights. 100 Nights of Hero gestures towards this long, rich and colourful legacy. A Rabbit’s Foot rounded up six more of the best.

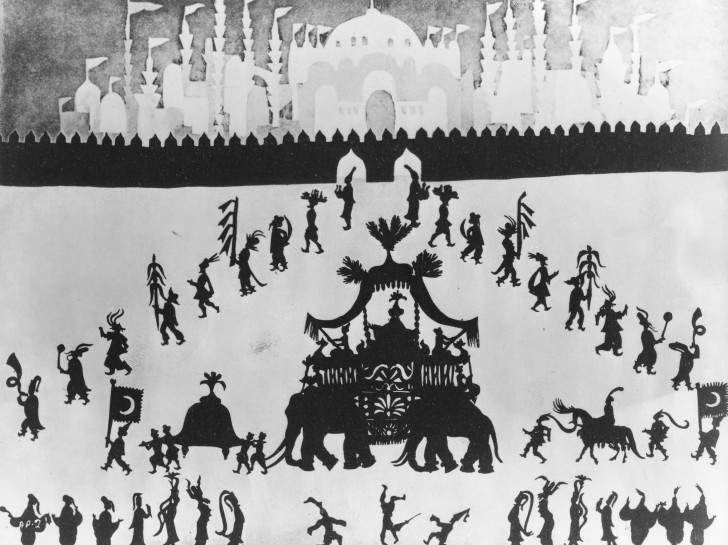

Revolutionary not only for being the oldest surviving animated film, but also for being among the first films directed by a woman, Lotte Reiniger’s pioneering adaptation of One Thousand and One Nights is among the most enchanting of its renditions. The German animator, who invented the first multiplane camera, wanted to use animation to tell a story which at that time, with its flying horses and magic carpets, would have been nearly impossible to relay through live action. Using a shadow puppet-style technique, sorcerers, demons, princes and genies are rendered with silhouette cutouts – scherenschnitte in German, meaning “scissor cuts” – which took three years to finesse. The result is a stunning showcase of storytelling and craftsmanship.

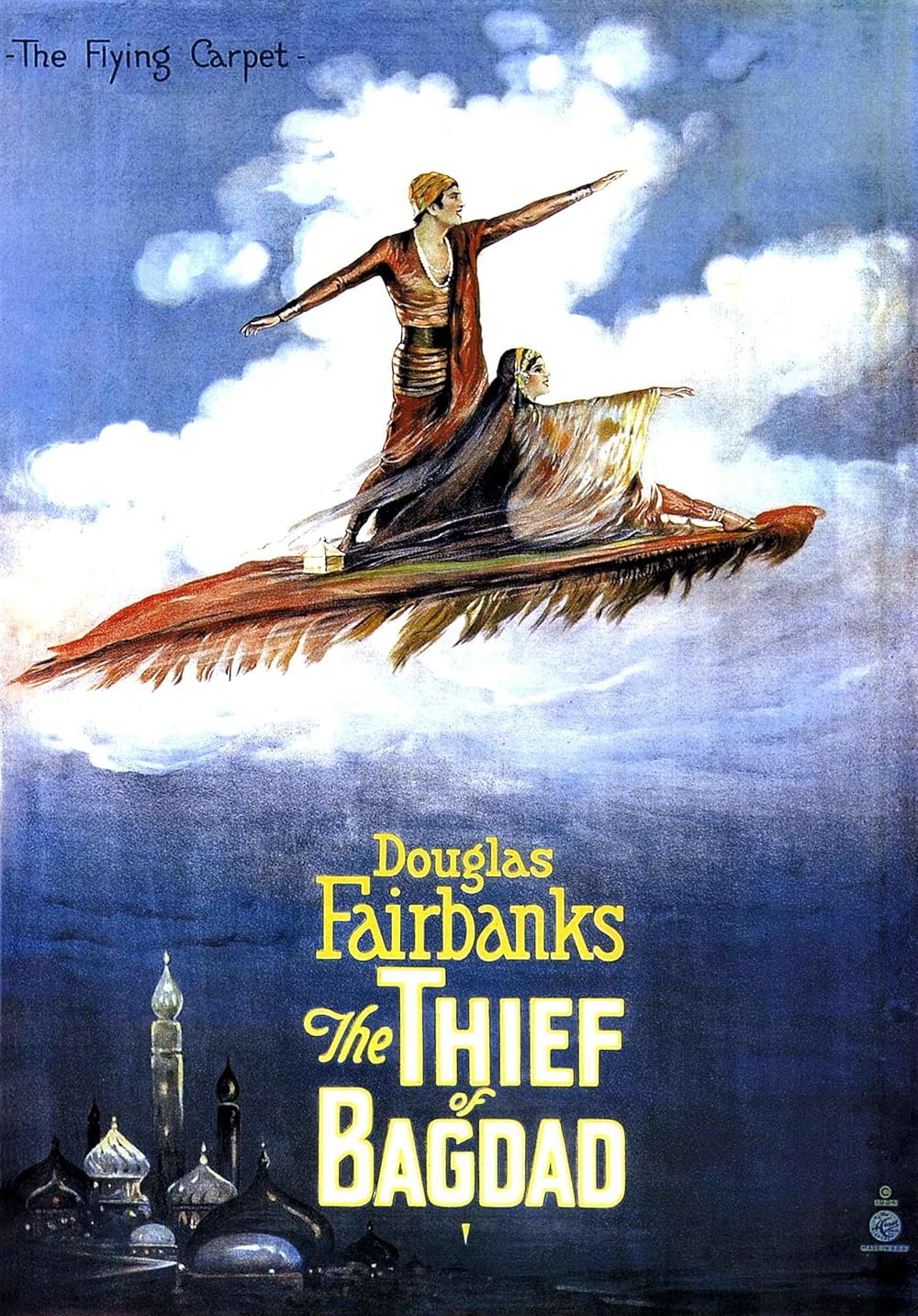

Featuring a career-best performance from Douglas Fairbanks – one of the silent era’s greatest stars – as a thief reformed by love, in this whimsical swashbuckler the actor problematically plays the Arab character Ahmed. Yet Walsh’s feature has gone down in film history for pushing forward the possibilities of what could be achieved with filmmaking. Replete with cutting edge visual effects (necessary to recreate flying carpets and other magic), staggering production design and a cast of thousands – including the legendary Anna May Wong and Noble Johnson – this cinematic spectacle is a must watch.

Riffing off the legend of Robin Hood, the robber of this film’s title, Abu (Sabu, who also appeared in the likes of Black Narcissus and The Drum), steals from the rich and gives to the poor – while also helping the hero, Ahmad (John Justin), of this fantastical fable to escape the clutches of the wicked Jaffar (The Cabinet of Dr Caligari’s Conrad Veidt) and reunite with his amour. This lavish, large-scale technicolour remake of Walsh’s 1924 film – guilty of some of the cultural appropriation of that earlier classic – was a truly collaborative effort, with Michael Powell and Tim Whelan brought in at the behest of Alexander Korda and their work unfortunately ground to a halt amid the outbreak of World War Two. Completed in America, the film was transformed into an anti-fascist allegory.

The origin of the phrase ‘open sesame’, this tale of two brothers and fraternal betrayal is turned by the prolific Egyptian filmmaker Togo Mizrahi (who directed 37 features during his lifetime) into a dazzling, entertaining and delectable feast for the senses. Egyptian comedian Ali al-Kassar is cast in the central role as the hapless, impoverished woodcutter Ali Baba, who discovers a hidden cave crammed with treasures, only to be sabotaged by his own sibling.

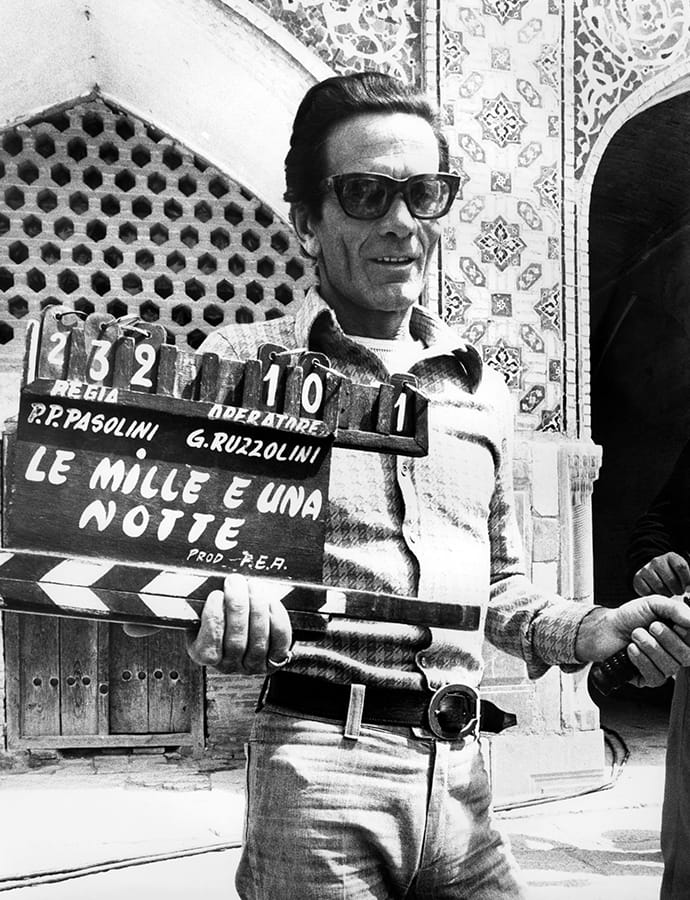

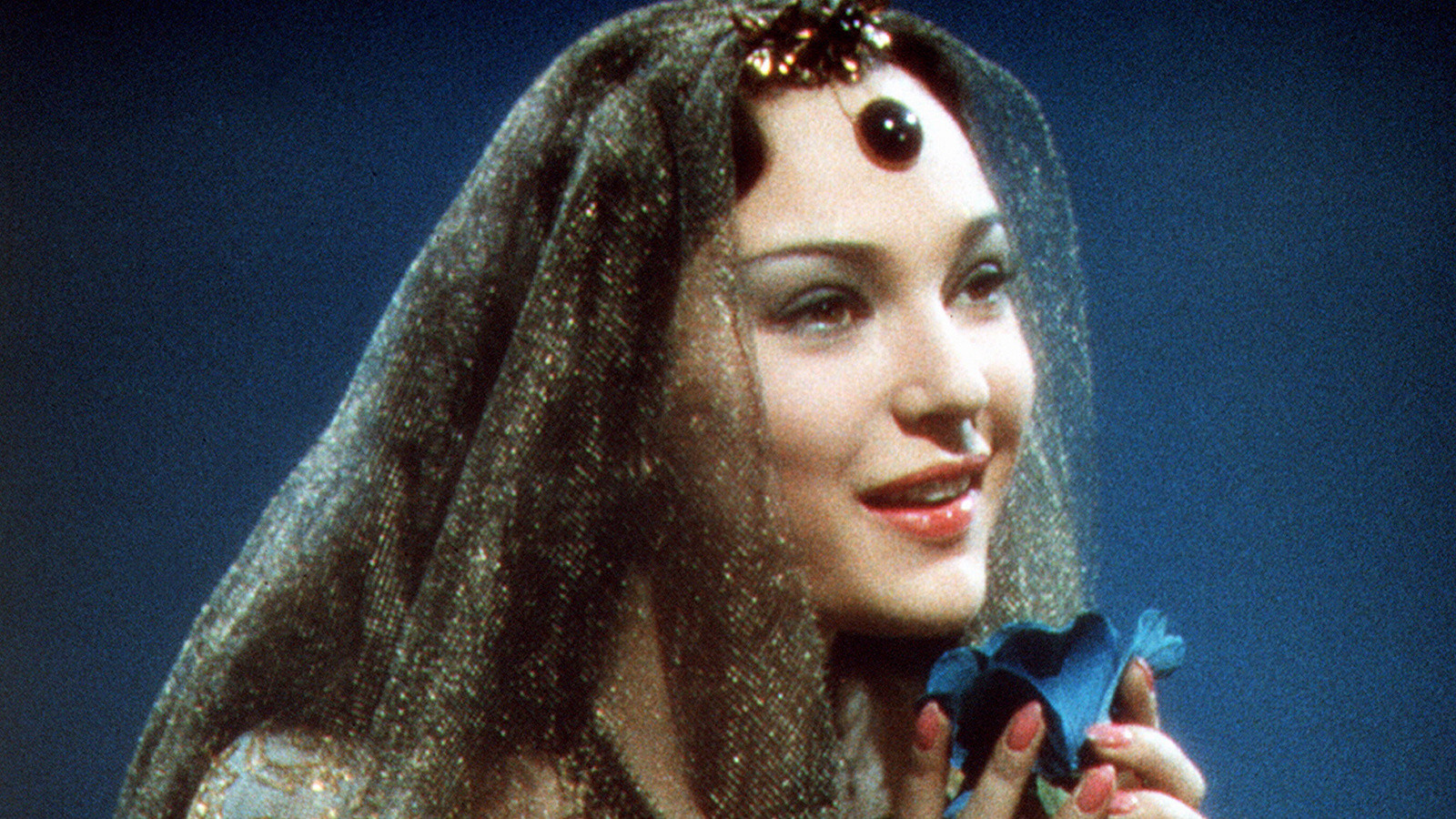

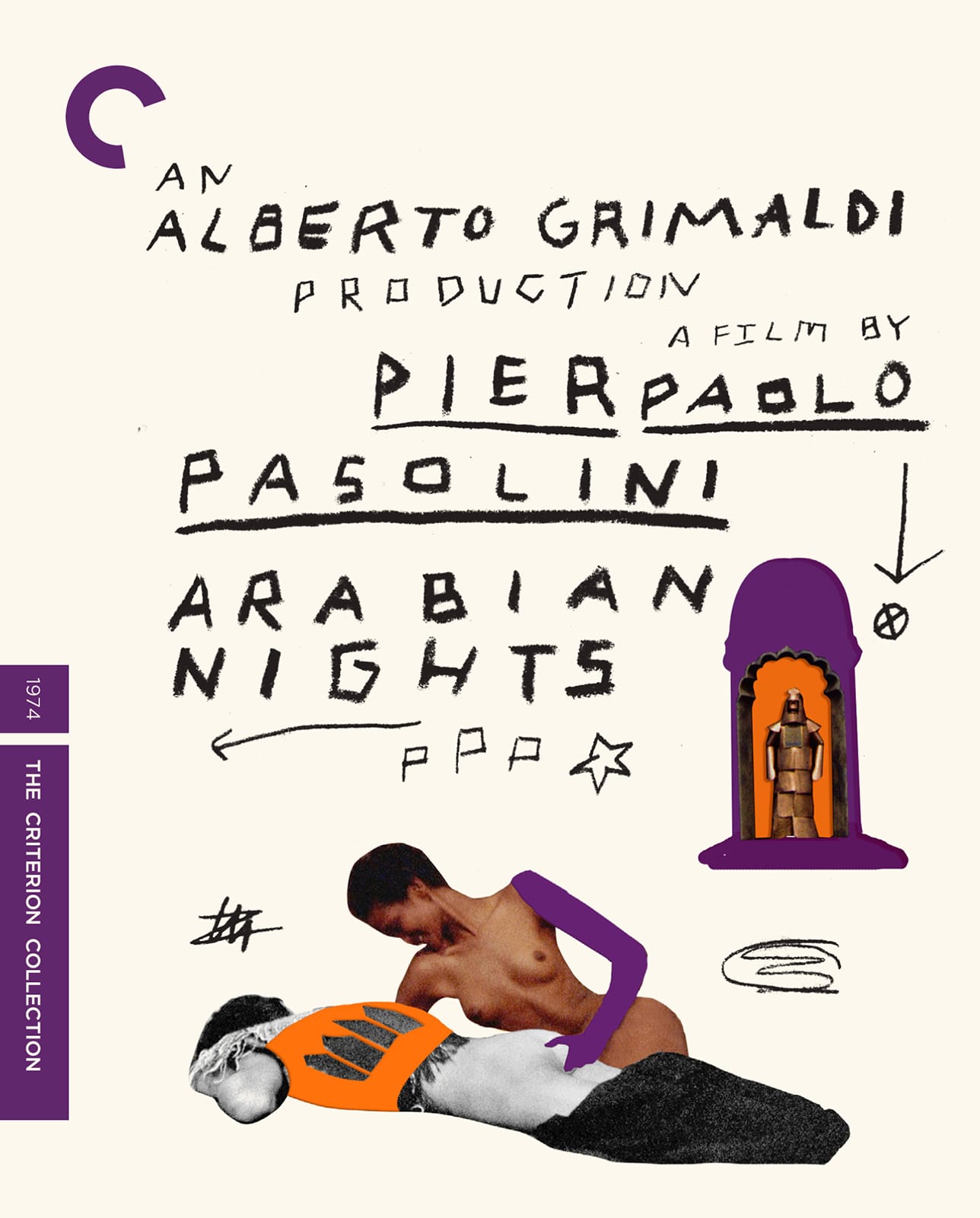

Before Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, Pier Paolo Pasolini directed another lesser-known but equally notorious, pot-stirring feature about unbridled sexuality and the parameters of desire. The Middle Eastern folk stories were reportedly a childhood favourite of his, but Pasolini’s resplendent drama is a defiantly adult take on those tales. Soundtracked by Ennio Morricone, the globe-trotting production spanned Yemen, Ethiopia and Nepal, taking in their most striking citadels and monuments. The concluding chapter of Pasolini’s ‘The Trilogy of Life’ – also encompassing The Decameron and The Canterbury Tales – Arabian Nights bends the rules of both gender and class.

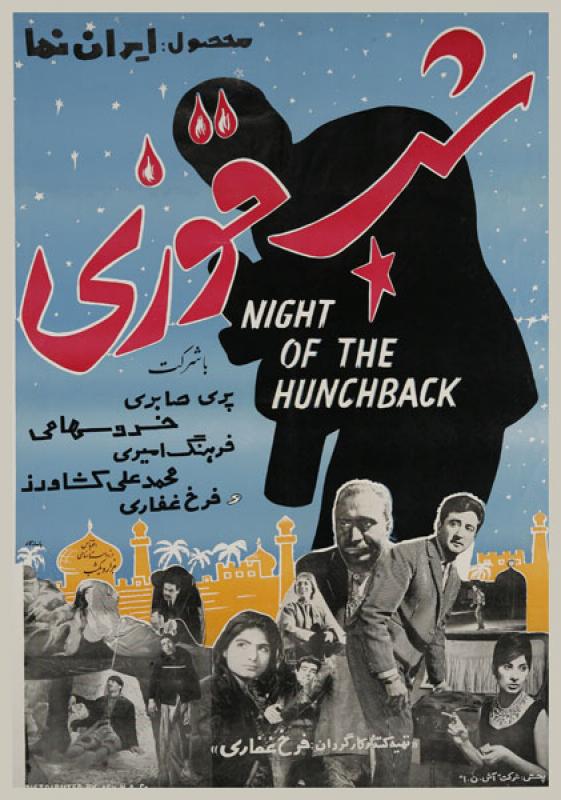

A pitch-black comedy of errors about an actor’s untimely demise and his friends’ farcical struggle to dispose of his corpse, Farrokh Ghaffari’s third feature premiered at Cannes Film Festival in 1964 and caused a storm. Iranian censors had strongarmed Ghaffari into transposing the One Thousand and One Nights tale from its ancient roots to a modern setting, but they did not anticipate that the result would be a scathing indictment of institutions and societal attitudes towards death, both biting and unapologetically nasty.

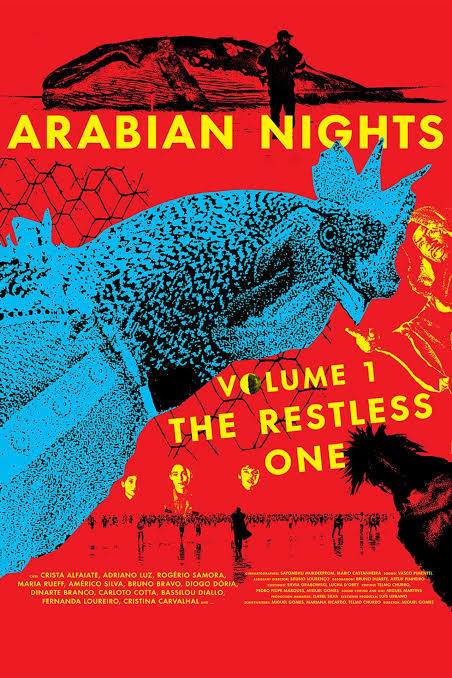

With this tri-part drama – comprising ‘The Restless One’, ‘The Desolate One’ and ‘The Enchanted One’ – Miguel Gomes used the One Thousand and One Nights format to address the political climate in his native Portugal. Premiering at Cannes Film Festival, this hybrid docu-fantasy triumvirate of tales recounted by Scheherazade interweaves stories of austerity, environmental collapse and unemployment. It’s an epic which expertly captures the absurdity of reality.

An ultra-modern, feminist update of these fantastical fables, for her version of Arabian Nights Julia Jackman creates a world of her own: a highly regressive, oppressive patriarchy in which ordinary women are tyrannized by an all powerful ‘birdman’ (Richard Grant). Jackman’s sophomore feature focuses on Cherry (Maika Monroe), who is not allowed to read or write and can dream of little except becoming a mother – or facing execution. But her cunning maid Hero (Emma Corrin) helps fend off bad men and give her a glimpse of a more hopeful alternative future and potential liberation.