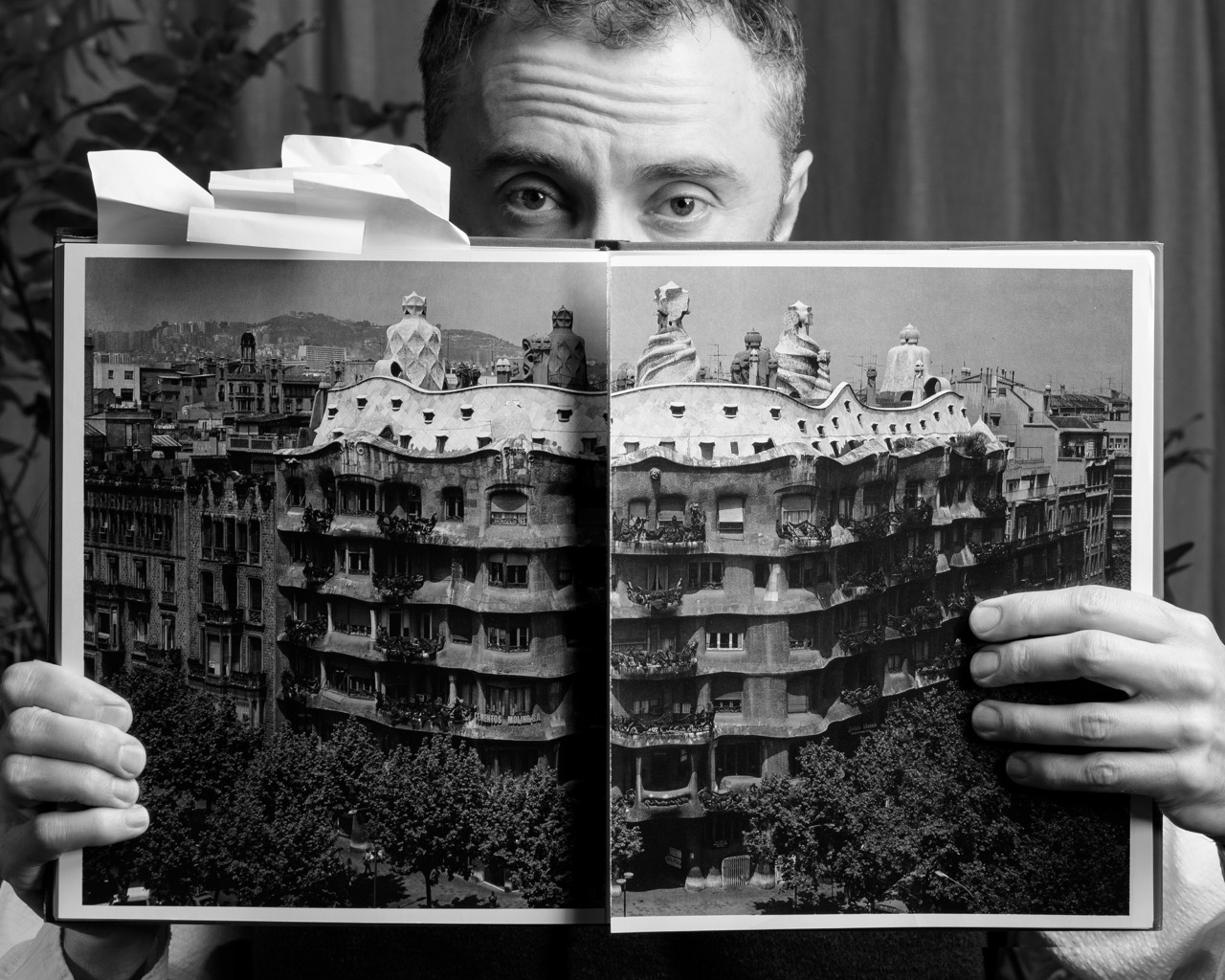

The acclaimed British designer discusses AI, whether Le Corbusier is the ‘God of Boring’ and the future of design.

Thomas Heatherwick, CBE, RA, RDI and HonFREng, is the most famous designer in the world. After doing a diploma in art and design in London, an undergraduate degree in 3D design at Manchester Polytechnic and a masters in furniture design at the RCA, his first commission came from Sir Terence Conran and at the precocious age of 24 founded Heatherwick Studio. Now, at the age of 55, he leads a team of 250 creative minds from his studio, Making House in King’s Cross. Famous for undulating buildings and nature-integrated wonders such as Azabudai Hills and 1000 Trees in Shanghai, Heatherwick has also designed an unfurling bridge, fantastical furniture, sculpture, Christmas cards, a pollution-eating car, a boat, a Longchamp ‘Zip’ bag, NYC’s ‘Little Island’ floating park, a bus and the blazing copper lily cauldron for the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympic Games. I was greeted at Making House by the back of a red Routemaster, The Friction Table, metal extrusion bench, shiny spinning top chair and a forest of lit-up maquettes. Thomas magicked the carmine Friction Table in front of us from round to long oval.

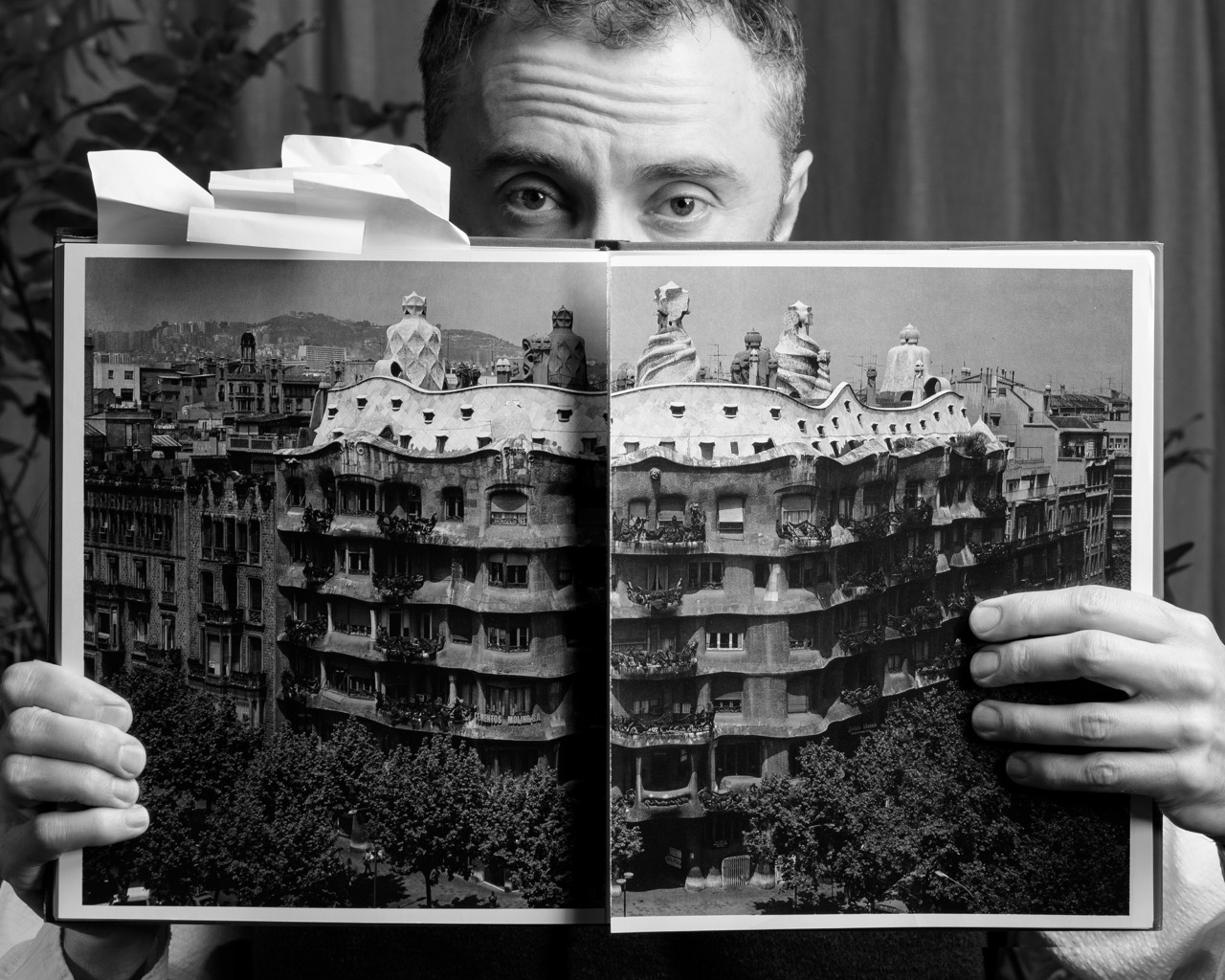

Extrusion Bench (2009).

Genevieve Gaunt: Your destiny as a designer feels inevitable. As a young child you dismantled typewriters and cameras. What’s the first thing you ever made?

Thomas Heatherwick: At primary school while people were playing football, I realised you could take a branch from the trees, file it on the concrete fence piers and use it as a tool.

GG: When did you know you wanted to be a designer?

TH: When I was 11 after my dad took me to the Design Centre. There were electronic knitting machines and pieces of furniture and novel appliances and I thought: this is what I am.

GG: Your mother’s jewellery shop had unusual signs saying ‘PLEASE TOUCH’. Can you talk about your family’s influence?

TH: My grandfather was a communist writer and a very good artist with books on engineering. My grandmother was a refugee from Nazi Germany. She had been to the Berlin equivalent of the Bauhaus and trained as a designer and later set up Marks and Spencer’s textile design studio. My mother’s jewellery shop on Portobello Road was an Aladdin’s Cave of reclaimed furniture and antique glass. My father’s mother was a servant at Windsor Castle and my father, aged 14, won the Purcell Prize as a pianist. I went to a number of different schools including a Rudolf Steiner School.

GG: You have worked with a cornucopia of materials. If you could invent a material what would it be?

TH: We built Google’s new Bay View headquarters in California and it was tantalizing because we had the Google founders saying, ‘design the building of the future. Let’s use materials in ways that have never been used before.’ We looked at gorilla glass. Phone screen material. In big sheets you can almost tie it in a knot. In theory, you could make a building draped with this cleanable, unscratchable, glass-like fabric but frustratingly, there aren’t factories big enough yet to make it. And it would take 10 years to get a warranty.

GG: Has 3D modelling on the computer revolutionised architecture?

TH: Yes, but if you look at what Gaudí was building a century and a half earlier with no computers at all… The biggest limit is our own intelligence rather than any particular tool.

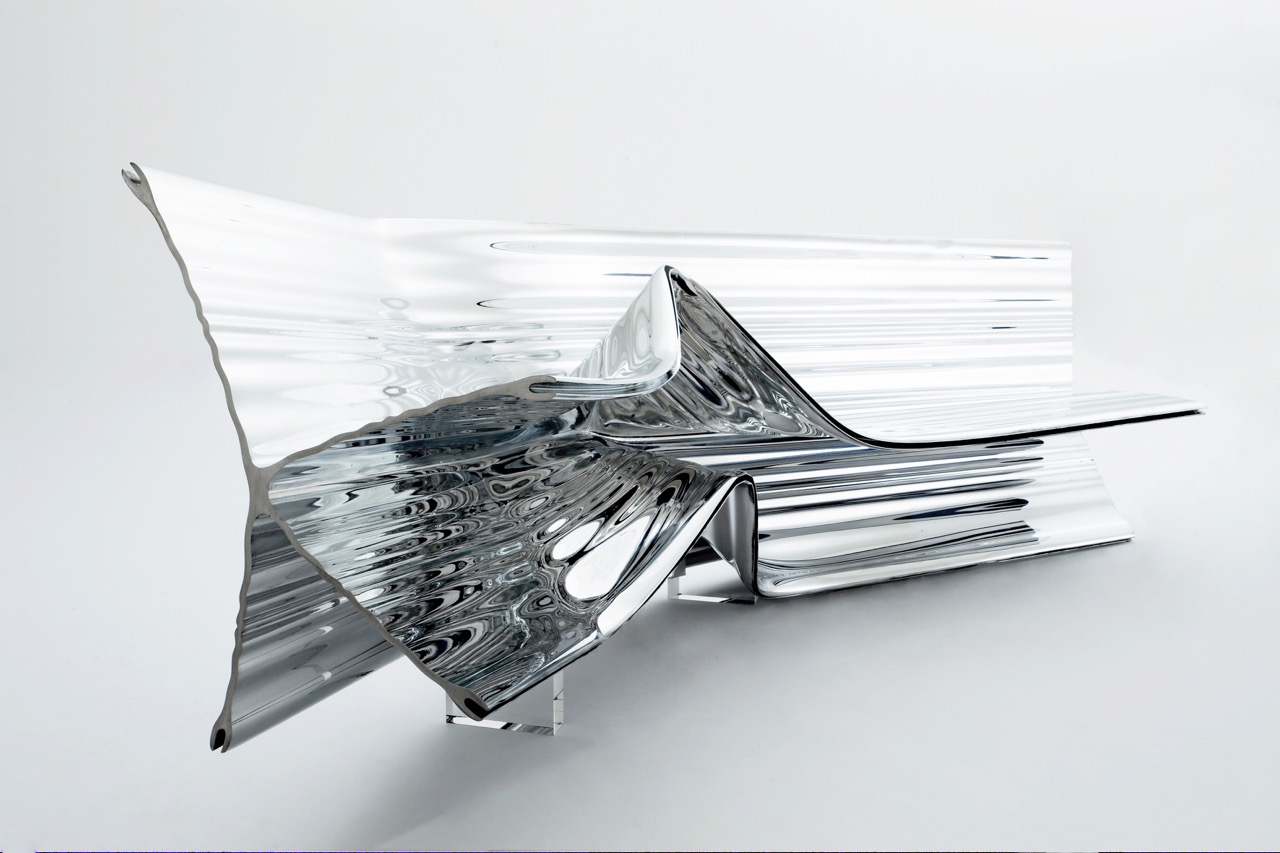

AIRO (unrealised) EV Pollution-Eating Car.

GG: How does AI help or hinder your work?

TH: We use it a lot in creating visualisations and drawing. Many software programs have had versions of artificial intelligence embedded in them for a long time. AI is a good synthesizer and trend-spotter but it doesn’t suffer, it doesn’t love and it hasn’t got a point of view. With design or art there’s a useful negativity required to create beauty. Maybe AI will be able to build very boring buildings, but they can only regurgitate what’s already in existence.

GG: You famously called Le Corbusier “The God of Boring”…

TH: Corbusier is the biggest paradox. His Chapelle Notre-Dame du Haut is one of my favourites. But he did advocate for mass boredom in his city planning.

GG: You write passionately about the malfunctioning effects of ‘boring’ social housing. Have you built any social housing?

TH: We haven’t and we’d love to. We need someone to ask us. I believe that there are ways to do it without it needing to cost a fortune. So much of what was built since WW2 has been demolished because it was so unloved. We shouldn’t build new towns that are demolished every 30 to 40 years. We have to make places that people care about to ensure their longevity.

GG: Our government announced the construction of 12 new towns. Are you going to have a voice?

TH: Our ‘Humanise’ campaign team have put forward some suggestions but we don’t have any formal role at all. Whoever is reading this… Heatherwick Studio wants to help build our towns of the future! Take note. Is there anything strange you’ve not designed that you’d like to? Bezos’s house on the moon? We don’t do private rich people’s houses just because there are people who do that already. And if you have the chance to do something that is part of hundreds of thousands of people’s lives rather than just one, it’s much more satisfying even if it’s less well paid.

GG: What is the status of the Airo EV pollution-eating car?

TH: It’s on hold at the moment in China… We would love that to happen.

GG: Speaking of vehicles, have you driven your Routemaster?

TH: I’m waiting for when they’ll decommission one. This whole studio is designed so that a double decker bus can drive in. They made 1000 of them. We will buy one as soon as we can. A standard bus has the least flattering light to human skin. You can still meet all the regulations without looking like you’re meeting the regulations—protecting the driver, designing clear handpoles without them being nuclear- war coloured. And between a Ferrari and a Routemaster, the Routemaster has the better view.

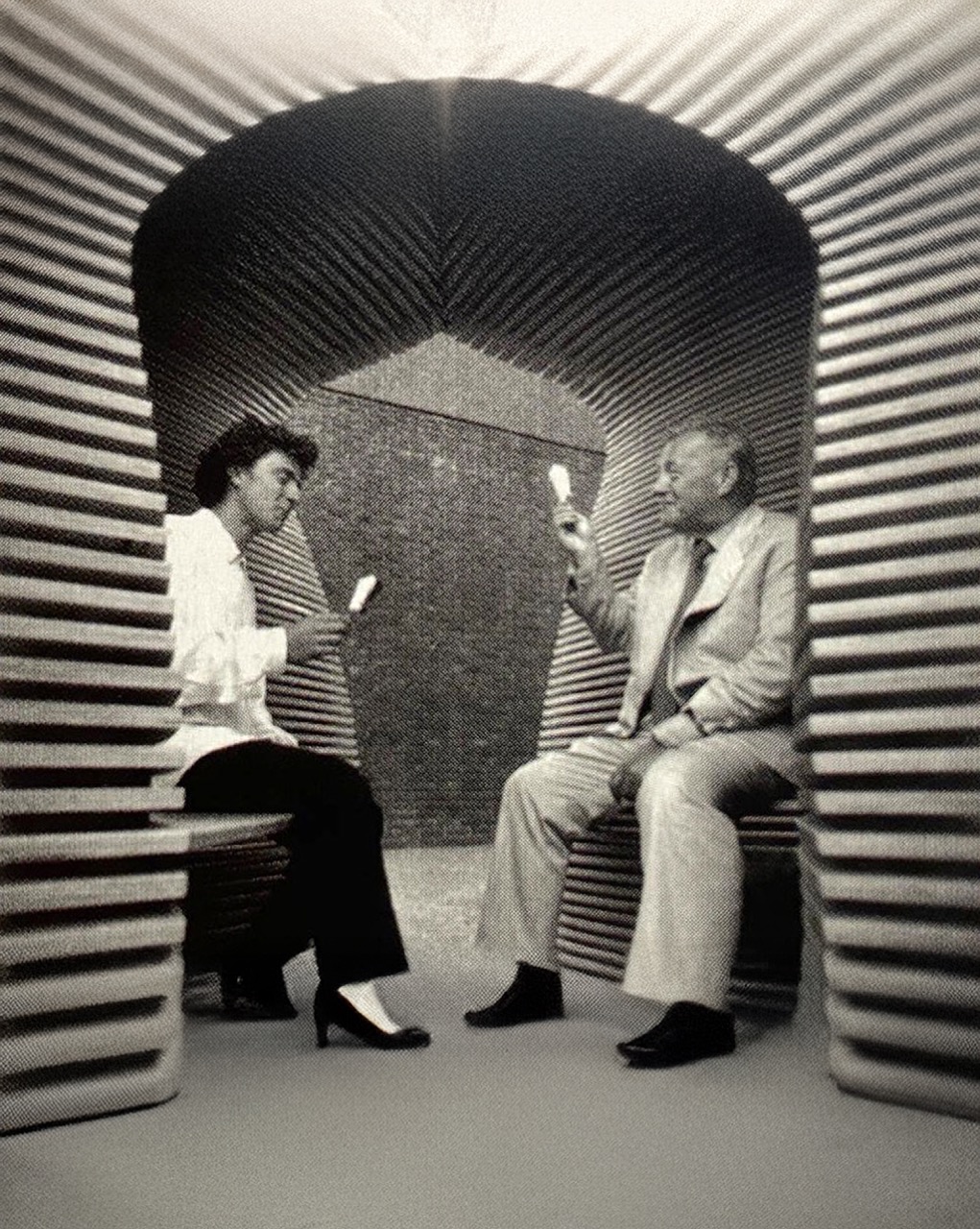

Thomas Heatherwick and Sir Terence Conran in the gazebo Conran commissioned (1994). Courtesy of Heatherwick Studio.

GG: Who has the ugliest buildings, the communists or the capitalists?

TH: Such a good question. Even though there have been some incredible monuments that have come out of the Brutalist time in the Czech Republic… Overall, the West has had more space for idiosyncrasy. Beauty is subjective. There are buildings that aren’t beautiful but they are still generous and engaging. So ‘engaging’ vs ‘boring’ is more useful.

GG: You have a test for judging a space. What is it?

TH: ‘Would you go there on a date?’ is the test. We also developed the ‘boring-o-meter’; a digital and objective tool where we measure the amount of articulation to see how three-dimensional or flat or repetitive a building is.

GG: Your designs are literally integrated with nature such as Tokyo’s Azabudai Hills, Shanghai’s 1000 trees, the Seed Cathedral and Little Island. What are the challenges of working with Mother Nature?

TH: Ultraviolet light attacks wood and even stone changes colour over time, it burns away.

GG: Like the gazebo you made for Sir Terence Conran?

TH: That actually doesn’t exist anymore. It got taken down. I want to rebuild it…

GG: Even your name is a design-moniker. ‘Heather’ for nature and ‘Wick’ for candlelight or the Old English for a town, ‘Wic’. There’s such an organic drive to your work. Why?

TH: I like watching the body language of a group of people. Trees, like horses, are great humanising forces and calm people down. I find nature as a way to create some of the effects that ornament and decoration have without deliberate design of the ornament and decoration. Probably, if everything was organic and soft and curved, I’d be the first person to do something really square.

GG: How does art influence your ideas?

TH: I love Umberto Boccioni’s futurist sculpture of the walking man. In the absence of a belief in religion we’ve grasped onto the artist and created a commercial trend like Art Basel, Frieze and the gallery system. We are missing a greater public spiritedness because it’s led so much by money. I think the art world is too in love with the art world. I’ve asked a number of artists if they would consider devoting 10% of their time to thinking about how that imaginative part of their brilliance could be public facing and not just in art galleries. We recently finished a project in Xi’an, China and in the first six weeks, 11.5 million people went there.

GG: Can you talk about your upcoming work with a football stadium, Olympia and Google?

TH: We are leading the design of the new Birmingham City Football Club and the bowl is being designed by MANICA who specialise in stadiums.

GG: Is Peaky Blinders creator Steven Knight involved?

TH: Yes. He’s a long-time Blues fan. He was a muse and mentor whilst we designed it. The design details will be public soon.

Thomas Heatherwick and Sir Terence Conran in the gazebo Conran commissioned (1994). Courtesy of Heatherwick Studio.

GG: What about Google HQ, King’s Cross?

TH: The Google HQ project is so big it’ll be another year before it opens.

GG: Olympia, Kensington?

TH: Next March 2026!

GG: What’s the longest running project?

TH: We are working on Singapore’s new airport terminal with KPF which will be double the size of Changi airport. We started 7 years ago and it will finish in 10 years. A 17 year project.

GG: So the buildings of the future are like the speed of light? The light that we are currently seeing…

TH: Yes, that’s it! The light is coming from a planet that’s already died. With some projects I think we’re only chosen because we’re young

enough to gamble on that we won’t die by the time it’s completed!

GG: In the future, will it be possible to use concrete and steel in a more sustainable way?

TH: Big efforts are being made to reuse materials and embrace imperfection. We humans are very smart: give us a problem and we can find ways to counter it. I have a lot of hope.

GG: Could buildings in the future gauge how people are feeling?

TH: At the creepiest level, there are CCTV cameras in China already in existence that can tell how people are feeling.

GG: Olympia is a £1.3 billion project. What’s your most expensive project to date?

TH: The airport in Singapore. Definitely upwards of Olympia.

GG: Any daily work habits?

TH: For the past 16 years I have kept a journal. Every day for 45 minutes. Journaling means you sort of catch life and then let it go shooting by again.

GG: Do you like Sci-Fi? Do you think about the topography of the future?

TH: When I was much younger I read lots of H.G Wells and Arthur C. Clarke. When a project launches it’s something we’ve designed years and years earlier. I’m in the ‘future business’ and it reminds me of that saying: ‘The best way to predict the future is to invent it’.