The actor talks the unlikely legacy of Jean-Luc Godard, his aspirations to direct a movie himself, and describes his first and last days playing Godard on the set of Nouvelle Vague, Richard Linklater’s biopic on the making of the French New Wave classic Breathless.

“It’s not only about Godard—it’s the history of cinema”, says Guillaume Marbeck, between eager bites of a much-needed morning pastry.

The French actor is talking about Nouvelle Vague, a biopic by contemporary independent film pioneer Richard Linklater (Dazed & Confused, Before Sunrise) about the legendary independent film pioneer Jean-Luc Godard, and, specifically, how Godard made his first feature, Breathless. Marbeck—32 years-old, in his acting debut—plays Godard, and is discussing the responsibility he felt while attempting to capture the essence of the French New Wave—and all of cinema’s—most well-known and beloved mavericks.

“I’m kind of disappointed when I watch a biopic and love the movie but later realise it’s not what really happened,” he continues. “I feel lied to. Movies are already a bit of a lie, because they’re all fake. They can only ever aspire to portraying reality, but they can never truly reach it. They are constructed—the costumes, the people passing in the streets, the camera. Everything is fake. So if we can find some truth in the story, there’s value in that. This is an idea Godard was fighting for when he was alive. He wanted cinema to contain a certain morality.”

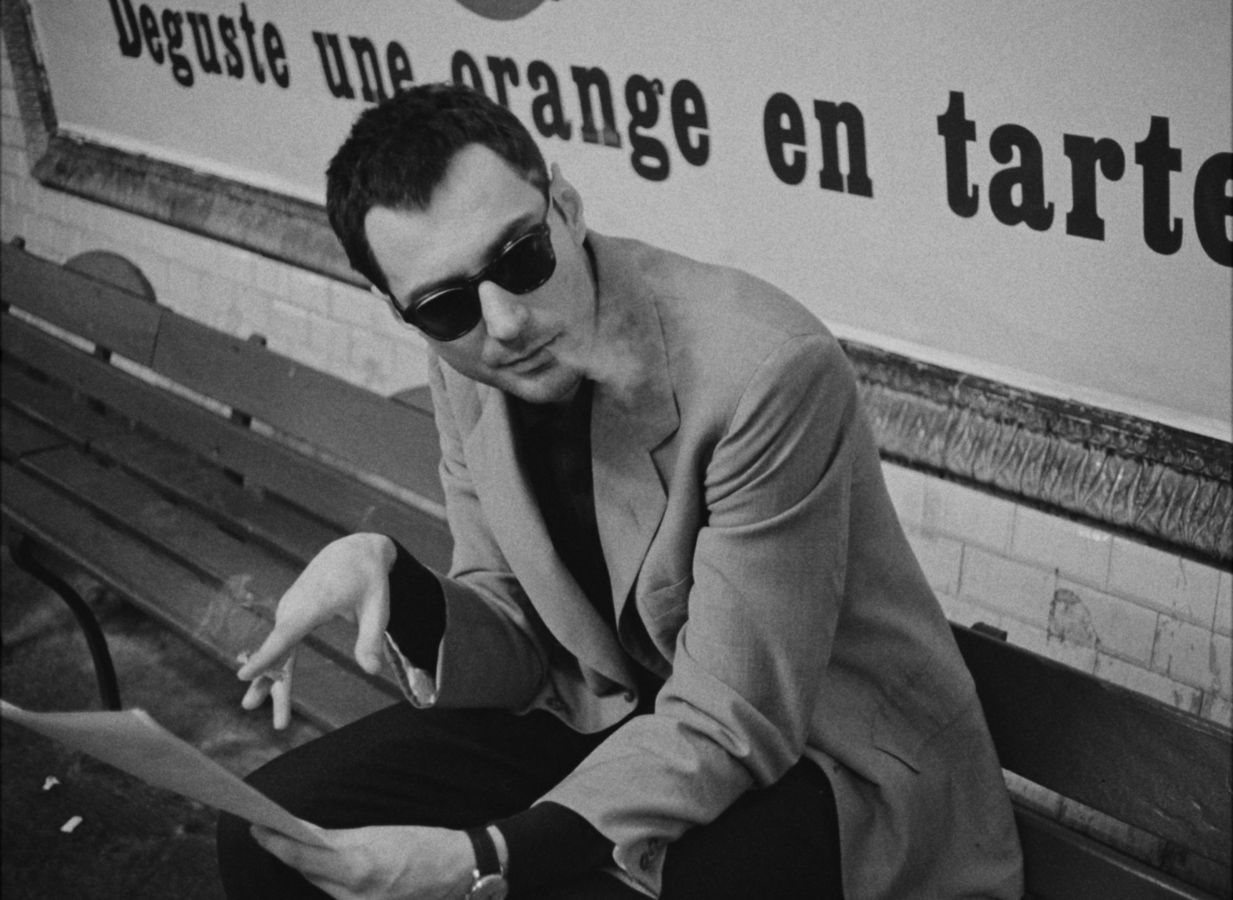

Marbeck, still channeling auteur-style—wearing washed denim jeans, a forest green crewneck over a collared shirt, and dark shades purposefully reminiscent of Godard himself—when I meet him in London, is a photographer by trade, but like Godard, who began his career as a film critic for Cashiers du Cinema, buried inside him is an aspiration to shake the world up with movies of his own. “I have a project for every budget,” he confirms. “From 50k to millions. But the one I have written right now is a modern romance set in the big city.” He isn’t the first and won’t be the last actor to try their hand at directing, but unlike many young film graduates who immediately sprint up the mountain in pursuit of budding legacies (and, I’m sure, an Oscar or two), Marbeck has been playing it safer and smarter, spending the last several years trying his hand at all the different roles that the filmmaking process offers. He has been everything from runner and production assistant to lighting assistant and, now, actor—an effort, he says, to understand and appreciate cinema from the perspective of every possible department. “I wanted to wait until I was ready,” he says. “But I feel ready to act on my dreams now.”

Below, we joined Marbeck to talk about the cultural legacy of Jean-Luc Godard, his first and last days playing Godard on the set of Nouvelle Vague, and why he’s finally ready to chase his wildest filmmaking dreams.

Luke Georgiades: What is the secret to unlocking a character like Godard?

Guillaume Marbeck: The key to unlocking a character that the world already has an opinion on is to focus on respect. Try to think, ‘if somebody had to portray me, what would that mean?’ Even when the person is dead, it’s even more important to ask yourself that question. That person isn’t going to knock on your door and help you do your thing, and they’re not going to tell you if you’re doing a great job or not. Godard is somebody who everyone has an opinion on, good or bad. It’s important to try to be as faithful as possible to who he was during the period we see him in the film, because it’s not only about me, it’s not only about Richard Linklater, it’s not only about Godard—it’s the history of cinema. I’m kind of disappointed when I watch a biopic and love the movie but later realise it’s not what really happened. I feel lied to. I don’t like that. Movies are already a bit of a lie, because they’re all fake. It can only ever aspire to portraying reality, but it can never truly reach it. It’s constructed—the costumes, the people passing in the streets, the camera. Everything is fake. So if we can find some truth in the story, there’s value in that. This is an idea Godard was fighting for when he was alive. He wanted cinema to contain a certain morality. When you have to portray him, who was all about this morality…..it’s a big thing [laughs].

LG: Do you remember your first time watching one of his films?

GM: I was with my friend, Clemont, and we were watching Pierrot le fou on a TV in my living room. At the end of the movie, I turned to him and said, ‘I think we’re too young to watch this.’ I was 22. I was used to watching movies about characters that need something and run into obstacles as they pursue it. Pierrot le fou is like a poem. It’s not something I was used to watching. I knew there was something, but I didn’t know what it was. Later, you realise that he was reinventing everything. He was like a scientist trying to research new ways of making cinema with every film. Then, it would be only work that people would steal from to make their own movies. So many great directors that I love have been inspired by his work. You might watch Breathless and think, ‘what the fuck is this?’, but then you watch a youtube video and realise that there are jump cuts all over it. Nobody had the guts to do that at the time. Now, it’s common sense. You don’t have to explain the idea of a jump cut to a kid watching a YouTube video. Audiences like their movies fast-paced now. Breathless was contacted at 90 minutes, so he cut every bit that wasn’t important.

Guillaume Marbeck and director Richard Linklater on the set of Nouvelle Vague.

LG: It’s an interesting idea, that he’s so in the bloodstream of filmmaking that a teenager instinctively knows and understands his technique.

GM: Yes. But he doesn’t know Godard. Of course, If you’re jump cutting today, you’ll just be doing what everybody else does. That wasn’t Godard. The real spirit of Godard was to break all the rules.

LG: Do you think often of what Godard would make of the film? Does it matter?

GM: It matters, because if he loved the movie no press would have paid any attention to it, but if he hated the film, everyone would be talking about it. So, in a commercial way, I would have preferred that he hated it. He could call me secretly and say, ‘that was fake, I loved it.’ [Laughs]. But who knows? We will never know.

LG: How did you handle the pressure of the role?

GM: The pressure stemmed from wanting to honour all the other actors who weren’t chosen for the part. I felt so lucky to have been given this role. I knew I’d have to give it my all, or never look at myself in the mirror again, because I knew there was another guy like me who came so close to it and missed. For that guy, I needed to deliver. I tried my best.

LG: What was your first day on set like? The first time wearing the costume and having the cameras rolling in front of you.

GM: It was awful. I was an extra before, and when you’re an extra on a movie, the reality is that you’re looking at those that are chosen to be the characters, and you think, ‘I could do a better job than them.’ So when I showed up on the set, I felt the look of everyone on me. They either could or could not imagine me as Godard. Maybe they thought he was shorter than me. Maybe they thought he wore glasses differently. I became paranoid. All the preparation I did became nothing on that first day. It wasn’t a game anymore. Now I had a gun to my head, and every minute that passed was lost forever. You can’t touch that minute again. The pressure got to me. The second day, I came back and I thought they were going to fire me. I had one line to deliver, and I delivered it. On the third day, I still wasn’t fired. I thought, ‘I might be okay at this.’

LG: What was the last day on set like?

GM: The last scene we shot was set during Cannes, where I [Godard] try and convince the producer to let me make Breathless. By then, I had just lived through the making of Breathless, so I had the confidence to convince him.

LG: Did you find it hard to let go of the character?

GM: It was hard to truly accept that I wasn’t living in 1959 anymore. I was back in 2024. There was less charm. The world outside of this movie hadn’t changed, but I had. The entire making of the movie soon started to feel like a dream. I had to look at pictures to make me realise that it really happened.

Guillaume Marbeck at Sea Containers hotel holding a copy of A Rabbit’s Foot issue 1 (featuring, on the cover, an image of Jean-Luc Godard). Photo by Luke Georgiades.

LG: You mentioned that the original dream for you is directing. Is there a passion project that you’re building towards?

GM: Yeah. I have a project for every budget, from 50k to millions. But the one I have written right now is a modern romance set in the big city.

LG: I like that you allowed yourself the time to grow into directing. You have purposefully experimented with many on-set jobs prior to acting. A lot of people want to climb the mountain too quickly.

GM: At first, directing is the place everybody wants to be. During my first week of film school, we were asked who wanted to direct. 300 people raised their hands. In the first week of our third year, they asked the same question again, and only around 15 people raised their hands. Everyone had found something that suited them better than directing. Directing is very long. You don’t know if your project is going to be made. It’s all uncertainty. You have to convince people that you can lead, and convince them that your project is worth giving a chunk of their lives to. There’s such opportunity for rejection. You also realise the audience isn’t joking with you. If you deliver a bad movie, you don’t get to make another. I wanted to wait until I was ready. But I feel ready to act on my dreams now.