At Cannes, Akinola Davies Jr made history with My Father’s Shadow, the first Nigerian film in the festival’s official selection. But behind the red-carpet whirlwind lies a film grounded in family, memory and the stories that shaped him.

When Akinola Davies Jr arrived at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, where his feature-length directorial debut My Father’s Shadow became the first Nigerian film to be a part of the official selection at the event, he was instantly swept into a maelstrom of praise and felicitations. His name was suddenly in the mouth of the likes of Angelina Jolie and Nicole Kidman, which was all very exciting, if a little disorienting: “The best analogy I can use is when there’s a surprise birthday party and everyone’s acting weird and someone’s bringing out a cake—that’s what it felt like.” Initially, there was no cake. Davies departed Cannes, “because it’s super expensive to stay there”, and went to Marseille with some friends. He began to hear that other filmmakers were getting call backs for the category he was presented in, Un Certain Regard, but he heard nothing. “So we’re like, ‘Oh, damn’. I was a bit perplexed, because I was like, ‘Why did everyone gas us up so much?’”

But good news delayed was not good news denied, as Davies would find while clad in hiking gear, scaling Marseille’s rugged terrain, only to be advised that he’d have just a few hours to change into a tuxedo and get back to Cannes for the Caméra d’Or ceremony. Iraqi film-maker Hasan Hadi would win the top gong, but Davies would win a Special Mention; Hadi would go on stage and make a speech, Davies would stand up and sit down. When he came to leave the ceremony with the other attendees, he was pulled aside to get his photo taken and sit at the press table to field questions from journalists. “It kind of felt like being on drugs, such a rush. Everything’s happening at 100 miles an hour. I’m just so glad it happened to me at this time of my life, because I think at any other time, I would have probably lost my mind.”

I meet Davies in his home in Walworth, where he offers me hawthorn tea and is repeatedly apologetic for the clutter. What I see is a charming ground-floor apartment, which is decorated with the spoils of his travels and treasures from his previous lives. There are wooden carved benches once possessed by Ghanaian royalty, a Marantz record player, Benin bronzes, a portrait by the artist Kay Davis from Davies’ days DJing under the alias Crackstevens, a poster of Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat that he says was “the first poster I ever bought at uni” (he studied English language and media at Brighton). Most intriguingly, there’s an obsidian chess set that he acquired in Mexico City in 2023. He tells me that he became infatuated with Mexico after his very first girlfriend told him about a community of Black Mexicans in Oaxaca, who had been in the region for generations. “I got obsessed with the idea of going and making a documentary about them. And that planted the seed in my head, that I’m curious about what the Black experience is in different parts of the world.”

Davies has just returned from Guadeloupe, the French overseas department, for the Monde En Vues film festival, focused on human rights, identity, and diaspora, which he’d been invited to as a guest of honour. There he screened My Father’s Shadow as well as his 2020 short film Lizard, which follows an eight-year-old girl who has the supernatural ability to sense danger, inspired by his childhood in 1990s Nigeria. It won the Sundance Grand Jury Prize.

My Father’s Shadow builds on those inspirations. A semi-autobiographical film, it follows two young boys, Akin (Godwin Egbo) and Remi (Chibuike Marvellous Egbo) as they follow their rarely seen father Fola (Sope Dirisu) through Lagos, gleaning information about the world he encounters and how he makes his wage—his oft-repeated excuse for his absence. The Egbo boys, real-life siblings, were cast after the team observed how “tactile” they were with each other—“one had his arm around the other”—while Dirisu had a face that “just has so much range”. In the end, the three actors create a family that is so resonant and identifiable.

The estranged Fola initially has the disposition of an intractable disciplinarian—his children obedient and shy in his presence. His absence has complicated their dynamic—there is an adoring fraternal bond, but also clear fractures as the eldest son carries flashes of resentment over the obligation to look after his brother. As they spend the day together, riding a ferris wheel, drinking fanta, and playing Marco Polo on the beach, Fola’s hardened exterior softens, and he begins to let the boys into his life. Beachside, his eldest son confronts him, asking him, if he loves Mummy, “then why do you keep making her sad?”. He seems unconvinced by Fola’s justification of his absence, but attempts to reconcile it: “[Mummy] also says that God loves us very much. So does that mean people that love us very much, we don’t get to see them always?”. It is tender and heartbreaking, a reminder of the wisdom children can carry and the granularity of their observations. Fola is silent, but soon answers, “everything is a sacrifice, you just have to pray you don’t sacrifice the wrong thing”.

It’s jolting, then, when this scene is disrupted by a scavenging crowd hacking at a beached whale, based on a real-life event. Davies explains, “Lagos is a place that can be super-still and then be super-chaotic in the blink of an eye. So we wanted to show Lagos as a completely fascinating character.” There is also a beautiful focus on the mundane. The rural opening of the film was shot in a part of Ibadan called Jericho, on the campus of an agricultural university. There, between nature shots of trees blowing in the wind and flies buzzing, the boys are eating ogi (a fermented cereal pudding) and arguing about wrestling. In Lagos, the restlessness and density of the city is captured by seas of yellow buses, livestock traders carrying goats on their backs, and all kinds of hustle and bustle; faces come into focus, from street sellers to a military convoy, and puppeteers entertain passersby. The benefit of shooting on a 16mm film camera was that “we couldn’t shoot loads, we had to be very precise, steal a little moment there”. That helped capture these documentary-like shots of the actors: “People felt a lot more natural. They didn’t feel like they were on camera having to perform.”

“Lagos is a place that can be super-still and then be super-chaotic in the blink of an eye. So we wanted to show Lagos as a completely fascinating character.”

Akinola Davies Jr

The backdrop of My Father’s Shadow is the 1993 presidential election, which was intended to transition the nation from military to civilian rule. M K O Abiola had won, but the results were annulled, leading to weeks of civil and political unrest, and the continuation of the military rule Nigeria had endured since the 1983 military coup, with dictator Sani Abacha eventually emerging as Head of State.

Davies and his older brother Wale, who wrote the script for My Father’s Shadow, were aged eight and 12 when this disorder unfolded, similar to the siblings in the film. His memories of this time are patchy, but he says: “We remember it being pretty traumatic for older people in our lives, not necessarily for us. There was a curfew. You had to put something on your car to show you were against the military. People were being wrapped up in tires, set alight; it was pretty hairy.” His reason for choosing this time as the setting for his film was to connect that sense of political and personal loss. “What Abiola represented for Nigeria was a promise, a political father that Nigeria never had,” he says. ”Whatever castigations people have of him now, he was a maverick politician, philanthropist, invested in education, sport; he had a newspaper. People were very enthused by this person who was going to come along and deliver on their promise. His campaign was Hope 93 [which is also the name of his son’s art gallery]. I think those two things—Nigeria not getting this father figure and the boys not getting their father figure—married each other pretty well.”

His memories of his father are even fainter. “Wale and I, unlike our older siblings, never really knew our dad. I was 20 months and Wale was three or four [when their father passed]. There’s a scene at the beginning of the film, which is the kids playing on the bed, and that’s the only memory we have of him.” Sope Dirisu’s Fola is not an exact replica of their father, and yet there was concern shared between the brothers over how to present the character so as not to dishonour their father’s memory. There is a scene with a waitress at a bar which suggests that Fola’s excuses for his absence are not entirely honest, and that he might have a mistress. “We really debated putting that in. Wale, who idolises our late father, was like, ‘We don’t want people to think less of him’. And I was like, ‘If people think less of him after we’ve done all this work then we’ve missed the mark’.” Davies has heard that his father was a “charmer”, and he knows he can’t account for everything his father would or wouldn’t have done. But most important was to “tell as honest a story as we can, because we don’t want to paint this perfect character. It doesn’t do a service to anyone if these characters are faultless. From stories from our Mum and sister, he was definitely a disciplinarian in as much as he was extremely charming. He could be emotionally volatile, but at the end of the day if you’re building a character, you want to create something that people can relate to.” Plus, it would be implausible to cast an actor as handsome as Sope Dirisu in a part where he’s away from home, and not acknowledge that either he would make advances at people, or people would make advances at him.

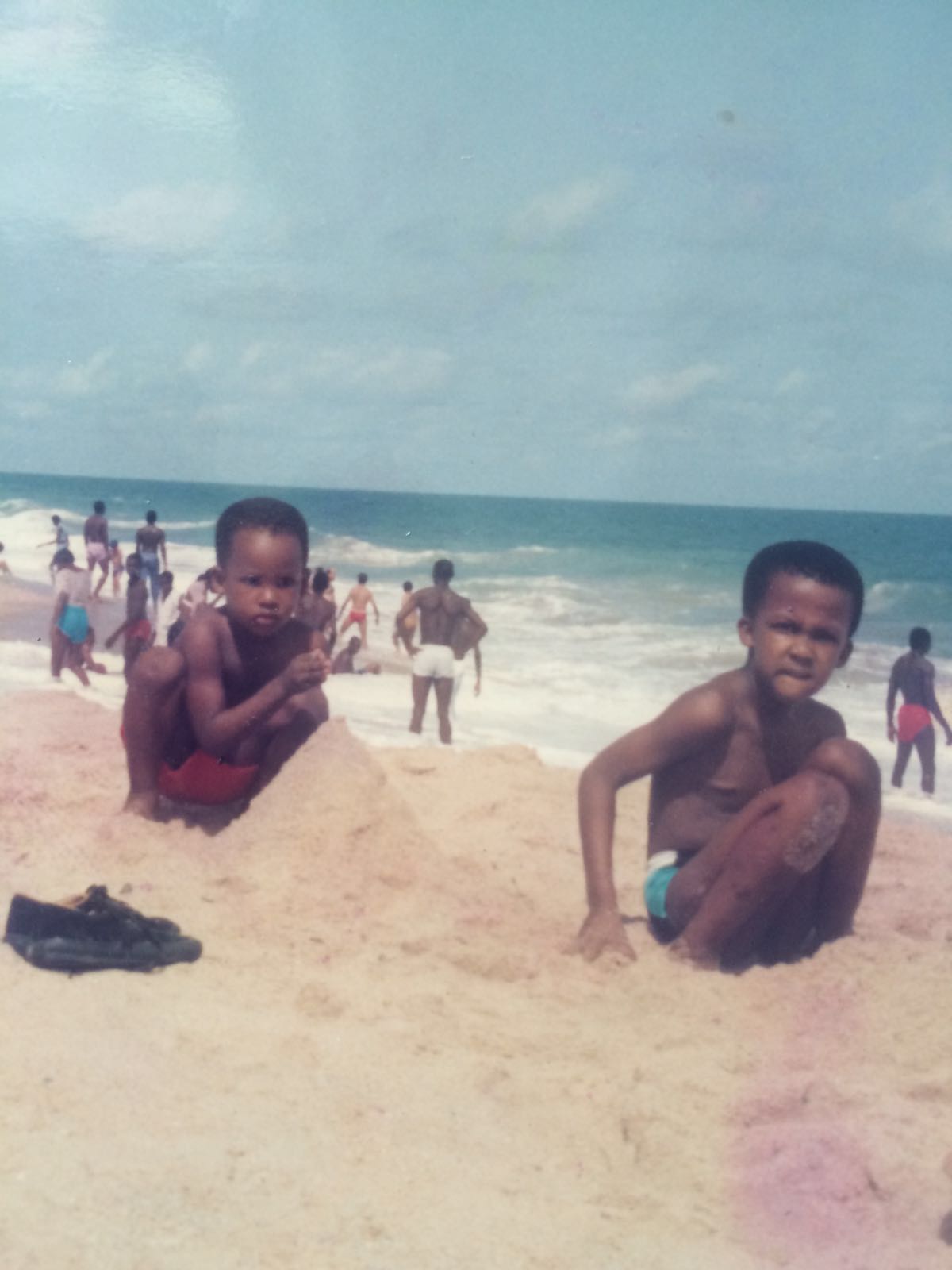

A childhood shot of Akinola and his brother Wale on a holiday in Nigeria. Eleko Beach, Lagos.

Still, the Davies family is imprinted on this film in myriad ways. The younger brother, Akin, is named after the director, and Davies himself is named after his father. In a way, the title of the film was extraordinary. After Davies was named, his mother had told his father, “You don’t want this child to live in your shadow”. Unaware of this story, his brother had come up with the title My Father’s Shadow. In the film the elder brother, Remi, is named after Fola’s brother who had drowned at sea. In real life, Davies’ brother was named after their uncle, Olawale, who drowned at sea. “At some point it becomes quite difficult to remove what it is.” But the big diversion between fact and fiction is that the Davies family was middle class, whereas the family in the film are from a poor, rural area. “We were always taken care of, maids or the driver or the cook. Those were the people we grew up with, so we were always curious of what they were missing out on, and about their stories.”

Davies was once content with the idea of never making a feature film. After the success of Lizard, he met with BBC film producers Eva Yates and Rose Garnett (who is now at A24) who had encouraged him to, after seeing Lizard and the music videos he’d made for artists such as Neneh Cherry and Dev Hynes. But he refused, not wanting to be “the Black guy who you give loads of money to, and I just make a mess.” He kept on being encouraged by the success of the short film, however, and once his brother Wale had a script, they received so many compliments on it, with remarks that it “read like a novel”, that they had no choice but to make it work. The Davies brothers have a remarkable working chemistry, and long-term collaborations: “We go somewhere really secluded and share a room. He writes, I take loads of pictures and I’m like, ’Can you work this image into that scene?’ We debate scenes out. We’re just like, ‘Yeah, but why? Why would this happen? Why would they say that?’”.

“I would like to stay on African familial dramas… My favourite director is Hirokazu Koreeda, and he seems to have made a whole career on just telling Japanese familial dramas. I love anyone who stans their culture that hard.”

Akinola Davies Jr

He’ll be continuing this partnership with Wale and, aside from the documentary he’s working on with Adam Curtis (details of which are under wraps), he’s thinking about his next few films. “I would like to stay on African familial dramas, perhaps with a supernatural element. My favourite director is Hirokazu Kore-eda, and he seems to have made a whole career on just telling Japanese familial dramas: Shoplifters (2018), Monster (2023), Our Little Sister (2015). And he’s unapologetically Japanese. I love anyone who stans their culture that hard.” And he’s learning from the work of other great directors: Andrei Tarkovsky and his lingering cameras, Alfonso Cuarón and his “360 sweeping camera”, the lighting of Spike Lee films. He’s picking up bits and pieces from different places, hoping to refract them all through different presentations of Nigeria, “Nigeria has a lot of things to talk about,” he says. “I would love to take a swing at talking about as much as possible.”

My Father’s Shadow is in cinemas from February 6th