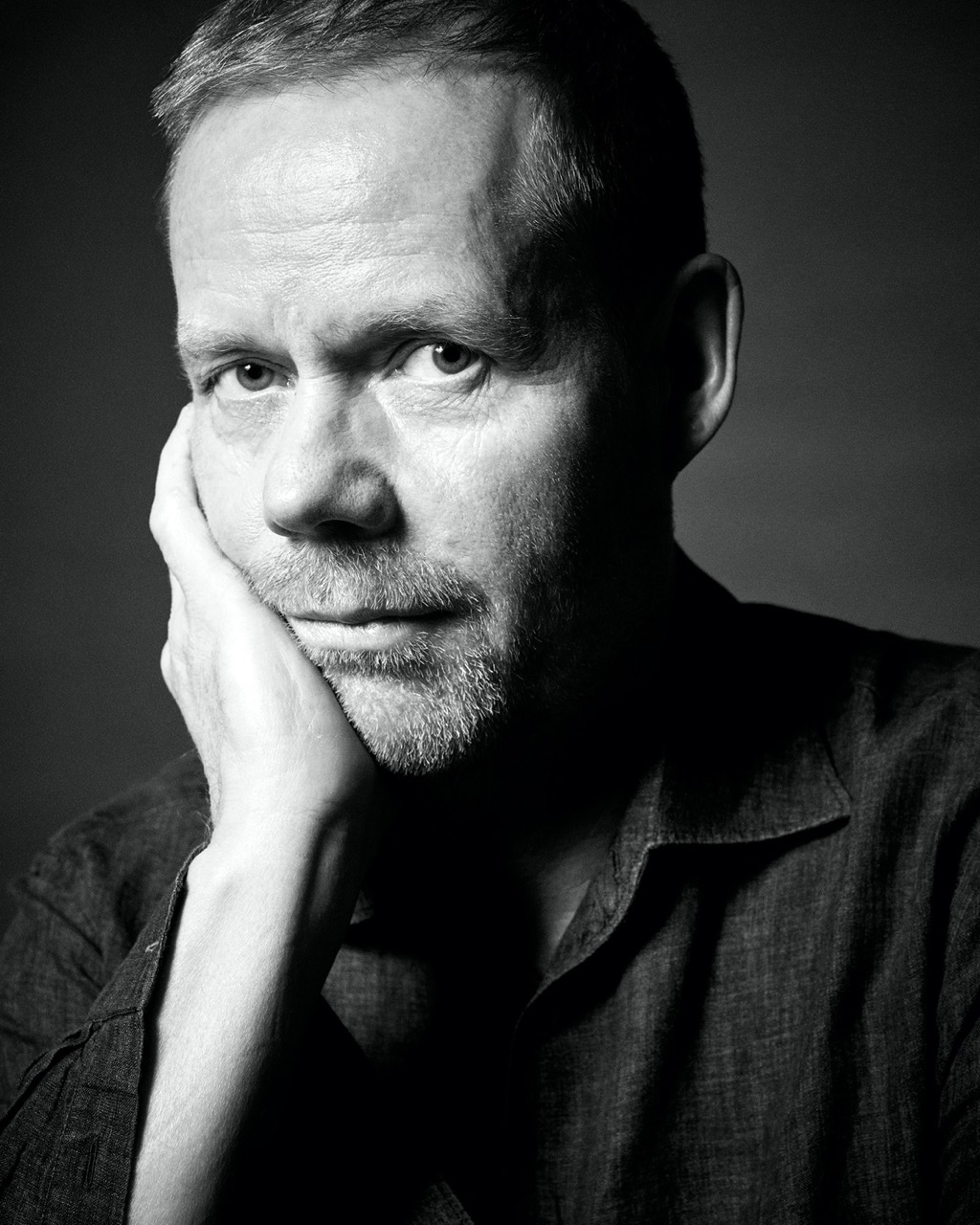

Max Richter is winning over audiences with his searingly emotional Hamnet score. Following a live performance in Southwark Cathedral, the acclaimed German composer speaks to Chris Cotonou about meeting Chloé Zhao, musical puzzle-solving and life in the English countryside.

We’re living in a new golden age for film composition. Across the board, from Jerskin Fedrix to Volker Bertelmann and Hildur Guðnadóttir, audiences are being exposed to geniuses of classical music through cinematic narratives. But the figurehead is German-British composer Max Richter, who manages to be as sublime, and consistent, in his solo work as he is for film projects. The most recent example is Chloe Zhao’s Hamnet, a story that conveys elements of English mysticism and folklore—the music written by Richter from his home in the woods.

I was fortunate to be present at the live recording in Southwark Cathedral. In silence, the candle-lit church became a dimension adrift from the world beyond its threshold; only broken as a sacred chorus delivered a hypnotic frequency that had us all completely transfixed.

This is what Richter does better than anyone, and why he even has mainstream appeal. His writing, whether it is the happy reimagining of Vivaldi’s Spring or his famous On the Nature of Daylight (an anti-war song) can bring one either to tears or beaming joy. Sometimes, as in the case of Hamnet, he does both.

Before the recording, and ahead of award’s season, I was able to meet with Richter—who I found completely unassuming for all his genius (the greatest always are)—on composing for the film. We discussed Ennio Morricone, Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums, striving for emotion, and why silence is sometimes the score’s most unexpected strength.

The emotive finale of Hamnet, directed by Chloé Zhao

Chris Cotonou: Can you share the first time you met Chloe Zhao?

Max Richter: The script landed in my inbox. When I saw Chloe’s name on the front, I lit up. I always admired her. We had lunch, spoke through her ideas and locked in right away. I felt that she is a visionary with a unique perspective, so I decided: OK, I want to be a part of this. Immediately, I began writing and made a bunch of material; a half hour of music which they began using even in pre-production, while searching for locations, cast and rehearsing. So the music was sort of there in the background before filming.

CC: It guided the atmosphere of the film from the jump. Chloe has also mentioned that the music actually inspired the film’s narrative outcome.

MR: Usually, the material at the start is a stepping stone for something else. But those early sketches stayed in the picture. A lot survived to the final cut. Chloe used them during the first edits and I continued to develop them as the edits were in progress and as she continued experimenting her ideas.

CC: How different is composing for cinema compared to other mediums?

MR: It’s another animal. I work across all kinds of mediums, but the solo records are my center of gravity. They’re me: sitting in a room, scribbling away. But movies are fundamentally collaborative. Hundreds of conversations about every minute details. That creates a puzzle-solving, collective dynamic that is fun, from the filmmaker to the actors. It’s a collection of interesting, smart people to experiment with.

Does cinema ever also inspire your solo work?

MR: Not really. I never set out to write film music, it happened because Ari Folman called me for [the excellent animated war documentary] Waltz with Bashir (2008). He had written it in a small hut on the beach listening to [acclaimed anti-war record] The Blue Notebooks (2004) on loop. He decided to email me and share the film’s sketches and ask if I would score it. I had no idea how, but it felt like an amazing chance to step into cinema. In terms of cinematic music, I’m into exploring the narratives. We human beings are storytelling creatures. And for me, that’s how the music connects to the cinema.

Max Richter with Emily Watson at an event promoting Chloe Zhao’s Hamnet.

CC: Do you have to go to a deep, often dark, place and immerse yourself in harrowing ideas when composing for films like Hamnet or Waltz with Bashir?

MR: I’m drawn to projects where I deal with the big details of life. Ideas that get me engaged; with themes we all must deal with, ultimately. Like the ending of Waltz with Bashir: I didn’t score it; it was my decision to stay silent. The same thing happened with Hamnet. There’s a lot of silence in that score. Because Jesse’s acting performance is so powerful; you don’t need a score to evoke the emotion. With material like that—these deeper films—it’s about what you don’t do.

CC: Do you think film scores are broadening the appeal of classical music and composers?

MR: I’ve not thought about that. The purpose is to write music you feel is authentic and real without questioning if someone will like it. I always assume no one is going to listen, anyway. So it doesn’t matter. But I do agree that cinema is a place where you can get out there and be experimental and more people will happily sit and listen and experience it as part of the film. If you try some of these scores in a concert hall, you might empty the room. But filmmakers certainly seem more open to non-traditional scores than before.

CC: How does instrumental music convey words and ideas?

MR: It’s a challenge. It always goes back to narrative. Music is there when words fail us. It’s a way for us to converse about ideas that you cannot talk about so easily. Often I work with found objects, found sounds and bits and pieces of text to give it a jumping off point in subject matter. You get that in The Blue Notebooks and Memoryhouse (2002) and other projects.

CC: Is there an emotion you’ve struggled to articulate, and even now, have yet to find a way of conveying through music?

MR: That happens all the time. Composing is mostly failing, right? You’re reaching for things that become unreachable and thinking of new routes, passing through the undergrowth to find the destination. And also, I’m never trying to retread the same route, I’m always looking for new ways to get to that destination, that emotion…

CC: On the Nature of Daylight is used often by filmmakers, including Martin Scorsese and now in Hamnet. Do you sometimes feel it can be mischaracterised? Does its use ever bother you?

MR: Yes. I’m cautious about allowing it in films. A lot of people call regarding that piece. It is from The Blue Notebooks, the subject matter of that record is essentially an anti-war protest from 2004. That’s what it still represents to me. But one of the nice things about creativity is how people apply their own perspective to what you do. You know… when I write a piece, it does sort of go out in the world and embark on its own journey. People connect to it in unexpected ways.

CC: You moved to the countryside. Does it help to be away from the cacophony of the city when you write?

MR: This house is the first time [Richter’s wife, artist Yulia Mahr] and I really had our own dedicated space. We were living in Berlin and had rented studios in a factory, and then we returned to the UK, renting again. Then, I was in the spare bedroom of a small cottage for five or six years. I did like ten movies and three albums in a tiny cube where I could almost touch the walls while writing. Not an ideal space—but when you’re in the zone it doesn’t matter where you are. Having said that, we found this old barn out in the woods and now we have this big beautiful studio with all my stuff inside. It’s made a huge difference also being so close to nature; we’re in the middle of the woods. So much of my life is working with technology, it is wonderful having green space to go out for walks and notice a world apart.

CC: I ask because Hamnet’s setting is largely in the English countryside. Where do ideas come from?

MR: Ideas simply pop into the mind. It happens when you’re walking down the road or halfway through a show. Just like that, a piece of inspiration will land in your brain and it will be for no particular reason. The best thing about being here, though, is that when it happens I can just run to my own studio nearby and get to work.

CC: David Lynch alluded to ideas being fish and artists being fisherman who must be prepared for the catch. How do you stay ready?

MR: I have no choice. For as long as I can remember, there has always been music playing in my mind, 24/7. That’s one of the first realisations that made me think I was slightly unusual as a kid; learning that none of my peers had songs constantly running through their heads.

I’m drawn to projects where I deal with the big details of life. Ideas that get me engaged; with themes we all must deal with, ultimately.

Max Richter

CC: Can you tell me a bit about Sleep Circle (2025)?

MR: It’s a version of The Big Sleep which is the eight-hour overnight piece. We played 25 shows over 10 years and every single one was difficult to make happen financially. It could turn into a disaster because of the infrastructure. I thought, I’m going to make a version of this that is condensed, which has more listening type material in it; and we’re going to perform it in concert halls like a gig.

CC: Is there anything you’re particular about when writing music?

MR: Most of the time, I’m taking stuff away. For me, a kind of economy and minimalism is essential. I prefer simplicity, finding the maximum from the minimum. That one note in the right place, at the right time. This is what I look for.

CC: How does it feel to be ‘in the moment’? In music, I believe it’s called ‘the pocket’.

MR: More than any euphoria, it is the feeling of inevitably. When you hear a track, and you think, ‘of course’ — that’s what I’m looking for. I will spend such a long time removing stuff just to arrive at that feeling.

CC: How important are other peoples’ opinions — obviously, those you trust — as you are writing?

MR: It depends on what it is. Cinema and ballet are collaborative, so there’s always a host of discussions. On solo projects, I tend to write through them from start to end, alone, and that’s it. It’s a space where I do what I feel is right in the moment. Once the thing is done, then people hear it but with the solo projects… it doesn’t really matter if they’re good or not, if you know what I mean. For me, it’s the process that matters. The personal journey.

CC: Is there a score in cinema you especially admire?

MR: I really like Ennio Moriccone. The blend of experimental and classicism is fantastic and he was also a great tune writer. One film which has a great score—that definitely doesn’t need replacing—but that I would have loved to have written was The Royal Tenenbaums. I remember seeing it for the first time and being so annoyed… I wish I had done the film. But the work is already fantastic. You can’t beat it as it is.

Hamnet is in cinemas now