As a guest columnist for A Rabbit’s Foot, writer and performance artist Harriet Richardson reflects on returning home for the Christmas holidays. Illustrations by Ciara Sansom.

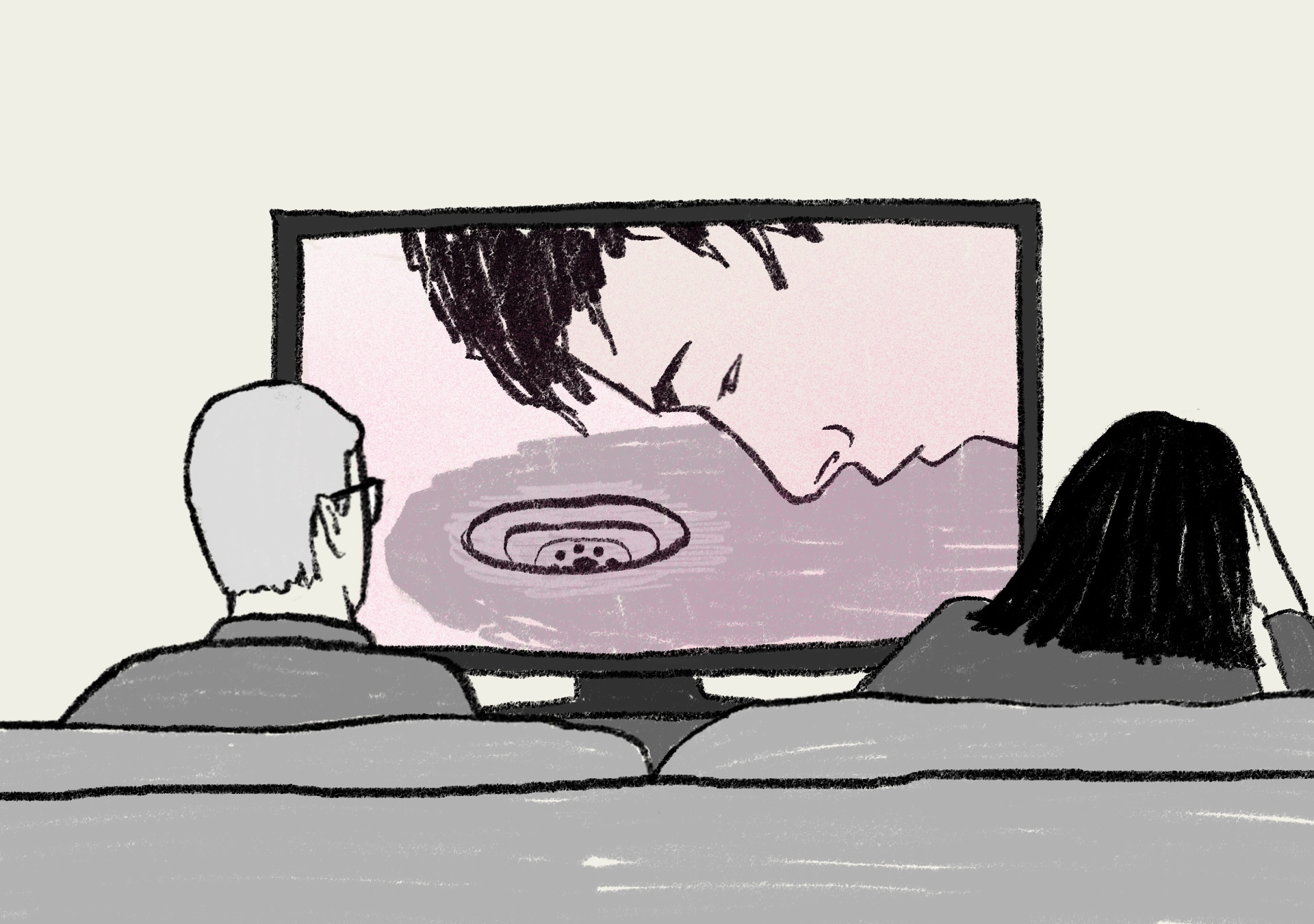

Whenever two people in a film are about to kiss, I focus on the space between them suddenly becoming a thing. Visible. Obvious. Emerging as the iceberg in Titanic, as Old Man Marley materialising on the church pew in Home Alone, or the tree bell in It’s a Wonderful Life as it starts to ring — faint at first, then impossible to ignore. A jigsaw piece of backdrop, shrinking as the characters edge closer together.

I know nothing of film making, my background is in art and design, but I imagine there must be some sort of magical trade-term for this space that asserts itself into focus. I’m going to call it Chekhov’s Kiss, because you’re never shown this space unless you’re about to view, at the very least, some tongue-in-mouth action.

It’s this same Chekhov’s Kiss that warned me to leave the lounge as a child, a teen, and now a 30-year-old adult returning home for Christmas.

The prickly anticipation as the camera lingers a beat too long, the sense that something intimate is about to happen in a room you very much still occupy with the same people who potty-trained you. A shared sofa, a shared silence, a shared understanding that this moment is not for you — and that if you stay, you will be implicated.

Why can I suddenly feel my face? And the placement of my hands? It’s in this moment I realise I’ve never heard waking-dad breathe before.

“Cup of tea anyone?”

“Oooo, isn’t it about time we open those Quality Street?”

“Are we going to miss the King’s Speech?”

…all said in unison over the symphony of orgasms leaking from the TV.

But sometimes — sometimes, it’s just too late. The opportunity for interception is missed. Mum frantically counting a dropped stitch. Dad immersed wholly in the local obituaries. My brother, Billy, suspended in the lounge doorway—mince pie in hand—calculating the floorboarded route of least creak-sistance.

And me. Me, sandwiched between the two people who conceived me thirty years ago, forced to watch on as I’m confronted with exactly how it was done. Well — provided my dad is Jacob Elordi and my mum is bathwater.

I know you don’t want me to say it, so I will: sexuality and Christmas go together like a satsuma in a stocking. Like one too many sprouts and not getting dressed. Like a Terry’s Chocolate Orange and The Vicar of Dibley. No one wants to admit it, of course, but I’m here to recreate the palpable tension of the above family scene, in the sentences below.

Arriving back at your family home as an adult (under any circumstance, let alone the biggest family occasion of the year) propels you back to the future whether you like it or not. You go from being a fully self-sustained, independent adult — all Aesop hand soap and Notion lists — to your mother bursting into your room at 6 a.m. to locate, with forensic precision, the one unwashed pair of pants simply begging for a synthetics spin.

“Don’t mind me!” she declares, as she fluffs the pillow my head is still very much on.

And with that comes the mindset too. Like many of us, the end of my twenties saw me embark on a journey of sexuality, discovering my likes and dislikes in a way that makes my formative teenage years look as sexual as the Yorkshire puddings you left in the oven. I’m no longer afraid or ashamed of who I am — so why, baby Jesus, why does my nervous system revert to Year-10-sex-ed mode the second I cross the threshold?

At the same time, there’s something quietly nostalgic about hiding yourself in your family home. It’s hard to be a deviant adult when all you’re rebelling against is the suggested bedtime of your Oura ring. There’s truly nothing like being sexted while your dad’s trying to carve up a turkey. Nothing like the ping of “opened your presents yet princess? I’ve got something to show you x” to test-drive your brand new iPhone as it sits innocently next to popped crackers and Bucks Fizz.

I’ll miss it when it’s gone.

For as long as I’ve known him, my dad has had a hearing aid.

There’s something quietly nostalgic about hiding yourself in your family home. It’s hard to be a deviant adult when all you’re rebelling against is the suggested bedtime of your Oura ring.

Harriet Richardson

As well as contributing to my domineering hand gestures and habit of announcing private thoughts at pub-quiz volume, it also means the TV is permanently set to aircraft-runway decibels. What could’ve been a subtle, breathy moan from Kate Winslet in the back of a 1912 Renault Coupé de Ville (yes I googled that— one for the dads) is broadcast as the fog horn they were very much lacking around 110 minutes in to the film.

One day, while I was escaping a particularly interpretive game of Charades for some battery-powered me time, dad knocked on my childhood bedroom door to ask if I wanted cream with my Yule Log.

“NO!” I shout— an attempt to stall what is about to become therapy material until 2036. Unable to hear my pleas, he enters. What happens next unfolds like well-rehearsed choreography:

I throw my travel vibrator to the ground in panic, simultaneously yanking the duvet to my chin.

At the very same time, he enters the room.

Chekhov’s Kiss takes on a whole new meaning as I watch the space between the protagonist—vibrating, pink—and the love interest—my dad’s bare foot—closing in.

“Oh my god, what’s that?” he exclaims. As contact is made, the magnitude of what’s just happened settles like fake snow in the globe of his frontal cortex.

No further questions, he Homer-Simpsons backwards into the shrubbery of the landing and, to this day, we never speak of it. Home, sweet, home.

It’s hard being at home.

Parents aging, brother just bought a house, the cat has a funny walk. Everything is familiar, but newly delicate. Under those conditions, of course we fall back on the coping mechanisms that have always worked: distraction, fantasy, and small, controlled escapes. Freud would call it regression; contemporary therapy might call it self-soothing. I experience it as endless snacking, videos of deep-cleaning carpets, and sexting a man with a boat from Raya— all while I pretend nothing fundamental is shifting beneath my (or my dad’s bare) feet.

As for the sex scenes, I challenge you to find a purer expression of the sanctity of family than watching one with your parents: libido surfacing precisely where it cannot be acknowledged, want trapped between good manners, soft furnishings, and an emotional climate in which no one is allowed to say what’s actually happening. Maybe this is better than being Home Alone.

Merry Christmas, ya filthy animal!

Harriet x

Harriet Richardson is a writer and performance artist whose work spans live performance, confessional writing, and visual practice, often exploring intimacy, desire, and addiction. Her recent and forthcoming projects include 100 Dates, Temporary, and Plastic, a large-scale performance scheduled for 2026. She is set to debut at the Edinburgh Fringe in 2026 and is currently working on her first book, with further details to be announced.