The Searchers was John Ford’s masterpiece—a sweeping Western that paired John Wayne with the vistas of Monument Valley. But making the film wasn’t always straightforward, as Chris Cotonou discovers in this essay.

When the producer, and head of the prolific Argosy Productions, Merian C. Cooper approached his old King Kong colleague David O. Selznick with the new John Ford flick, the movie mogul sneered at the thought. Just as in 1939, when Selznick rejected Ford’s Stagecoach for being “just another Western” he presumed that this tale of revenge would be as much of a monumental failure as the famous valley itself.

Whatever grievance Selznick held for Ford, the producer of Gone With the Wind would find himself, once again, proven wrong. The Searchers remains the defining Hollywood Western: a savage, disturbing film driven by rage and set against the magnificent backdrops of the mythical West—a change from the director’s cheerier, light projects like Stagecoach or 3 Godfathers, and an epic tragedy that would influence a period of violent, psychological stories that shaped the modern Western, even up to now. Based on Alan LeMay’s source novel, which itself is inspired by the true story of the 1863 kidnapping of Cynthia Ann Parker, we follow Ethan Edwards (John Wayne), a Confederate soldier visiting his brother’s family in Texas. During a Comanche diversion, the family is murdered by their leader, Scar, who also kidnaps the youngest daughter Debbie (Natalie Wood). Ethan vows revenge, and assisted by the young Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), promises to rescue Debbie no matter how long it takes.

The film famously takes great liberties with LeMay’s story, going as far as switching the author’s focal character from the sympathetic Pawley to the brutal Ethan, a man driven by his seething hatred of Native Americans. But Wayne’s version is the absolute opposite: a world-weary warrior who wears his prejudices with pride—and yet his quest for revenge is as heroic as it is brutal. These socially formed ideas (groundbreaking for a Western) were owed to an adapted screenplay by the recently Oscar-nominated Frank S. Nugent. The former New York Times writer left his journalistic fingerprints in this more complex and human approach to LeMay’s story and characters.

Script in, filmmaker and star onboard—but Selznick very much against the project—Cooper set about seducing businessman Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney to finance the film. Known as ‘Sonny’ in upper-class circles, C.V. Whitney could have been a character from an F. Scott Fitzgerald novella; a Gatsby-esque playboy who dabbled in cinema for the kicks, and had a penchant for gambling on the horses. He finally took the risk and backed The Searchers after taking an immediate shine to Ford. His wife, Mary Lou, would recount Whitney’s first impression: “[Cornelius] loved his pictures and loved the man. Ford was so totally different from anybody he had been brought up with. For a man who had relatively little education. He could read a script and see what could make a character click. He could also get you so riled up you were ready to fight.” That may be, but as neither Ford or Cooper had anticipated, Whitney would prove to be a thorn in their sides.

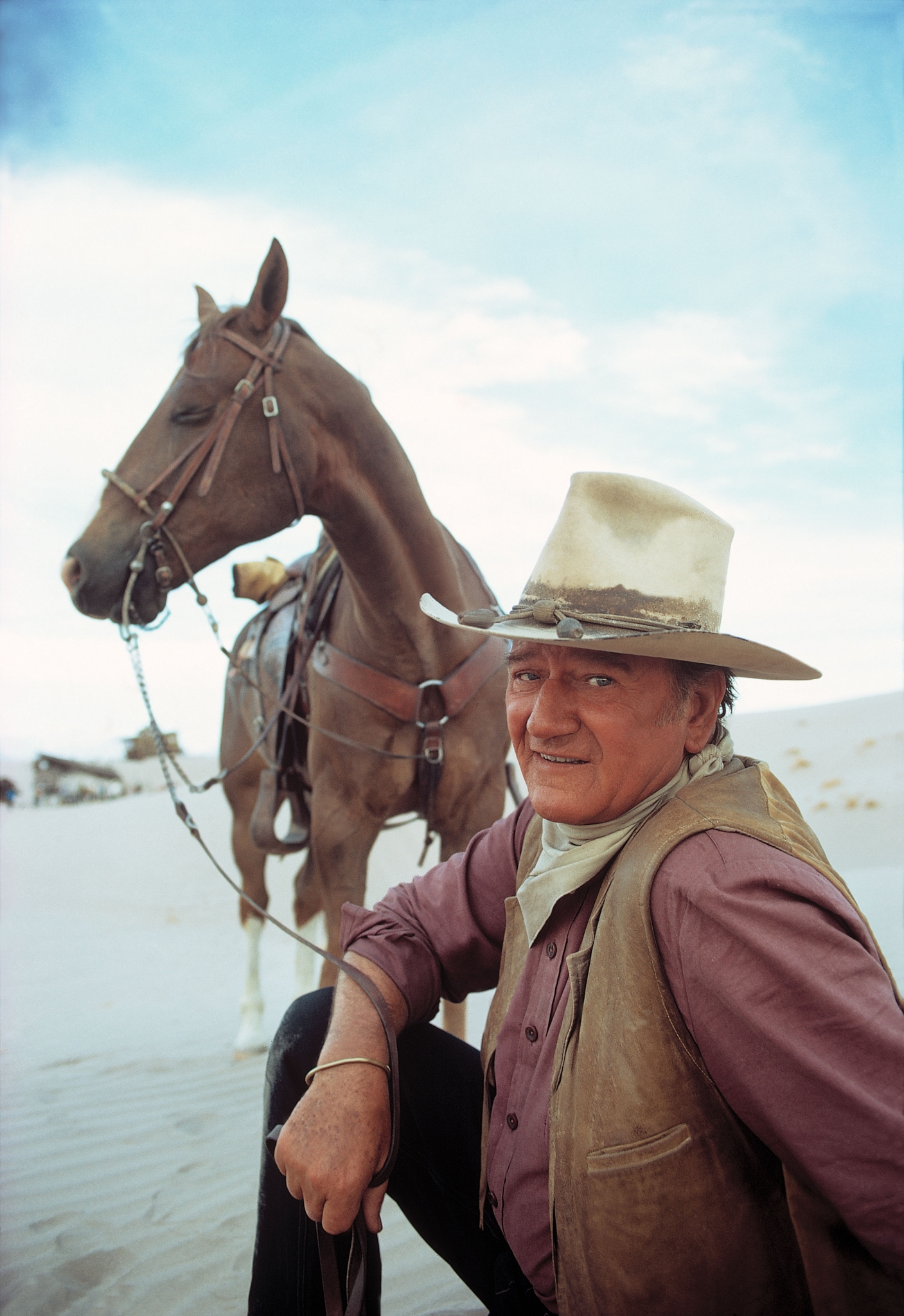

John Wayne in The Searchers (1956). By John Ford.

“He had the meanest and coldest eyes I have ever seen. Perhaps he’d known someone like Ethan Edwards as a kid. He was Ethan at dinner time. He didn’t kid around on The Searchers like he had done on other shows.”

Harry Carey Jr. on John Wayne as Ethan Edwards

The director realised early on that The Searchers was going to be one of his most important films. He sent a letter to Michael Killanin, an Irish journalist, friend and collaborator on The Quiet Man, saying that the script was “a tough, arduous job as I want it to be good”. He had been longing to do a Western for quite some time, he wrote, “It’s good for my health, spirit and morale.” His commitment to his own vision of LaMay’s story meant that he could often be belligerent and mean when it came to his casting. While John Wayne was always going to fit comfortably into the callussed gloves of Ethan Edwards, Martin Pawley was a trickier proposition. He had originally wanted Fess Parker, whose performance as Davy Crockett on TV had impressed Ford, but Walt Disney, to whom Parker was under contract, refused to allow it. Ford regular John Agar, who by that point had drifted into B movies and had tried for the part, recalls that for the resolutely Irish-Catholic Ford “my divorce might have had something to do with my never working for him again”. Robert Wagner opted out after the brutal treatment he received while shooting What Price Glory? He was humiliated by Ford one evening when the director teased the role to his face in preliminaries only to immediately rescind his offer. “It’s the kind of thing that can keep you up at night,” the actor recalled 40 years later. Eventually, he settled on Hunter.

Ford was just as uncompromising with the character of Ethan Edward. And who better to lead the line than John Wayne? The Duke’s portrayal of Edwards was, as the pair had established over their many projects, always built on an equal understanding; and this was to be Wayne’s most unforgiving character so far. It was a role that he relished: the righteous, tight-lipped American with a steely core. The actor would embody Ethan’s mannerisms off-camera too—one of the few times he would embrace method acting. Harry Carey Jr., who plays Swedish neighbour Brad Jorgensen, recounted his first rehearsal with Wayne: “He had the meanest and coldest eyes I have ever seen. Perhaps he’d known someone like Ethan Edwards as a kid…He was Ethan at dinner time. He didn’t kid around on The Searchers like he had done on other shows.”

When Ford began production on June 13, 1955 in the searing dusty heat of Monument Valley, Utah, he brought the same intensity in his own work. But Ford had also returned to his happy place: the American wilderness—a place of freedom. A month later, he surprised his crew by spontaneously throwing a Fourth of July celebration for the indigenous Navajo population, who in turn gifted him with a ceremonial deer hide that proclaimed him their “fellow tribesman”. Perhaps the filmmaker found more in common with the citizens of the great Western outdoors than the cast and crew he was forced to work with.

One of those folks was Whitney. The eccentric financier was seemingly always around during filming, poking his nose into production and causing a scene when the director was accidentally stung by a scorpion. “It’s OK,” Wayne consoled the pale-faced Whitney, “John’s fine, it’s the scorpion that’s died.” Although the pair had struck a friendship—and Whitney had expressed awe at Ford’s management of the thousands of extras, and his eye as a filmmaker—he still nonetheless tried to chime in with ideas of his own which infuriated the proud, stubborn Ford. Far from home, the excited Whitney was restless in Monument Valley and had heeded the call to adventure.

John Wayne on the set of The Searchers (1956). Photo by Raymond Depardon.

Since he was still signing the cheques, a compromise had to be struck to keep Whitney entertained, and the task fell to Ford’s son Patrick. The younger Ford would take Whitney out horse riding (by all accounts he was awful at that, too), or devise new, creative distractions. But Whitney still found a way to intervene where he was not wanted, insisting on being one of the riders who attacked the Indian camp at the film’s climax. “That was the worst thing about Whitney and his money,” remembered Pat Ford years later. “He had to be right in the middle of everything.” However, Ford Jr’s patience would later pay off. Whitney would go on to produce a smaller budget film, The Missouri Traveler, working with Pat after their experience on The Searchers. Ford Sr would repay Whitney’s intrusions by being a constant nuisance on set.

Back at Monument Valley, the right balance had to be struck so Ford wouldn’t lose his temper—not just with Whitney, but with his cast and his recurring crew. It was a conscious choice: harangued by stories of his bullish behaviour on the set of Mister Roberts, Ford tried his hardest to focus on making his movie without any off-screen drama, becoming uncharacteristically calm (although he was still prone to a famous outburst from time). This deeper attentiveness to his craft meant that he found efficient ways to improve on his original vision. He was like a painter making careful adjustments and strokes on instinct, choosing to do up to twenty-four setups on certain days when he wanted to, and subtracting dialogue or replacing images that felt wasteful.

Ford wrapped up the on-location shooting on 10th July, with only a few interior scenes to be filmed in a Hollywood studio lot from the 18th of that same month. At a cost of $2.5m, in a state of complete focus, and just a week over schedule, the director had finished his magnum opus.

Anything John Ford directed was a commercial success, and The Searchers was no different. Audiences flocked to the cinemas to see this darker take on the Western genre, thrilled by the gunfighting sequences, the sweeping sun-baked vistas of Monument Valley, and John Wayne. Critics, however, were mixed. The New York Times writer Bosley Crowther called it a “ripsnorting Western” but faulted the exhaustive violence, while Variety suggested that it was “somewhat disappointing” because of its length and a weak story. The British filmmaker Lindsay Anderson, an outspoken defender of Ford’s, would say that it was “self-conscious and unconvincing”. But in more contemporary times, and perhaps because the film’s glaring brutalities are conventional enough to not distract from its brilliance, The Searchers is recited as a masterpiece—John Ford’s very best, and commemorated by the American Film Institute as the greatest Western of all time. And yet, the film seems obscure to today’s audiences (Glenn Frankel would cite it as the best Hollywood film ‘few people have seen’). While it still remains as ripsnorting as Crowther claimed on release, The Searchers is unable to escape its politics, many of which are incompatible with the modern moviegoer. On its handling of race relations, the famously level-headed critic Roger Ebert wrote, in no hyperbolic terms: “I think Ford was trying, imperfectly, even nervously, to depict racism that justified genocide.” The Dixie hero riding off to battle against the savage Comanche was an image that thrilled audiences in 1956; a time before Civil Rights and Native representation in cinema. But in 2024, the film’s themes ask us some uneasy questions, and Ford was relentless in confronting us with these questions.

John Ford shot eight of his most famous films in Monument Valley, starting with Stagecoach (1939) and ending with Cheyenne Autumn (1964).

Its most enduring influence is in the visual poetry of the West that Ford conjures; alchemically transmuted to us in those sweeping scenes of Monument Valley, with its towering ochre rock formations that feel unreal or otherworldly.

Chris Cotonou

Its most enduring influence is in the visual poetry of the West that Ford conjures; alchemically transmuted to us in those sweeping scenes of Monument Valley, with its towering ochre rock formations that feel unreal or otherworldly. It had an immediate impact on other filmmakers: when David Lean was preparing Lawrence of Arabia (1962), he repeatedly rewatched The Searchers to understand how to shoot desert landscapes. Filmmaker Sam Peckinpah would reference set-pieces from the film in his Major Dundee (1965) and the excellent Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974). Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Paul Schrader, and Wim Wenders (particularly with Paris, Texas) have all made movies inspired by the visual desolation of The Searchers. Star Wars, a franchise largely set on the desert planet of Tatooine, reflects Ethan’s story when Luke Skywalker discovers his homestead has been burned and his family are murdered. There are comic book adaptations aplenty, and unofficial, often experimental, sequels: the first being 2007’s Searchers 2.0, directed by Alex Cox (Sid & Nancy); and in 2016, a Canadian reimagining titled Maliglutit (which translates to Searchers in Inuit) that follows a native man who seeks his kidnapped wife and daughter in the gorgeous expanse of the Arctic tundra. The Searchers’ legacy might sound like a whisper to today’s moviegoers, but it is more of a Chinese whisper that continues to be passed on and reinterpreted over subsequent generations.

But it is the final shot that best immortalises the spirit of The Searchers. Filmed in the late afternoon, Ethan brings Debbie home. As she and Martin enter the doorway and move off-screen, we see Ethan outside boxed inside the frame; the darkness and mystery of home shrouding the bright wilderness where he feels at home: the world he knows versus the one he never has known. “It just included a dark doorway,” John Wayne recalled. “It was emotional, and as they went in the door in the dark and got out of sight…there was just me in the doorway and the wind blowing.” It is a rare literary idea. In few places in Ford’s films had a moment like this appeared, but his pursuit of symbolism would define the second part of his career.

“The Searchers is the beginning of the last stage of Ford’s career,” explains Scott Eyman in his biography of the director, Print the Legend. As he aged, Ford lost interest in his montages, in editing, and “his style became increasingly theatrical.” Subsequent movies would be on a smaller-scale, and allow Ford to explore his themes: a decision that expressed the ageing director’s palpable melancholy in movies like The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and the unremarkable 7 Women. The Searchers was one of his last truly romantic films, made by a disillusioned romantic who was haunted by the failure of his dreams. Perhaps Ford had expected more from it. The film earned a decent, but not groundbreaking, $5.9m worldwide, was overlooked by critics and audiences for now forgettable movies like Around the World in 80 Days and Giant, and hadn’t earned a single Academy Award nomination and was the only modern American masterpiece to be spared an Oscar nod—a crime when we consider Ford’s direction and Wayne’s portrayal of Ethan.

There were early warning signs. While The Searchers was still in post-production, Cooper—who was Ford’s most committed champion—had decided to dissolve Argosy Productions for good. Investors earned a 30% return almost entirely due to The Quiet Man. It’s interesting to consider how Selznick must have felt after seeing the company close shop during production, and having refused Cooper’s advances for financing. Would he have felt vindicated in his decision not to invest in the film? Was The Searchers really just another John Wayne Western? To quote Ethan Edwards: “That’ll be the day!”

With great hindsight, the answer to both of these questions is obviously a no. The Searchers is the definitive Western, and the most emblematic film of the great John Ford’s career. Its lack of critical appreciation on its release is also a lesson in the way movies evolve over time; through new audiences who have new perspectives, and a sense of awe at discovering a master and an actor at the very pinnacle of their creative talents, pushing a genre they themselves cultivated to frontiers it had never gone to before.

John Wayne as Ethan Edwards in The Searchers (1956). By John Ford.

Foot Note

Our Pick of John Ford’s Essential Westerns:

Stagecoach (1939)

My Darling Clementine (1946)

Fort Apache (1948)

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

Rio Grande (1950)

My Best Friend (1999)