America is a commercial soul.

Signs are our perfect workers. With almost no upkeep, they’ll generate a fantastic return. Whatever words we bind them to, they’ll beam out that command till they drop. If there is one fatal flaw, it’s with us. Wait too long by a stop sign. Look at a red light. Rarely, ever so rarely, we get a contrarian impulse.

At first, Lee Friedlander’s pictures in Signs (2019) are hardly symbolic. Friedlander does not style himself as a deep man. At 90 years old, this legendary photographer—who counts Joel Cohen as a personal fan—ended his prior collection on real estate with a picture of his mother-in-law’s underwear. His reason? It was “funny”. (It really was quite the large set of briefs.) Despite his fame, he’s also happy to tell the last journalist he’s officially spoken to that he lacks the intelligence to tell you what most of his pictures mean. A photo happens so quickly. It’s not his job to work it out for us, it’s yours. So what the hell is he doing with Signs?

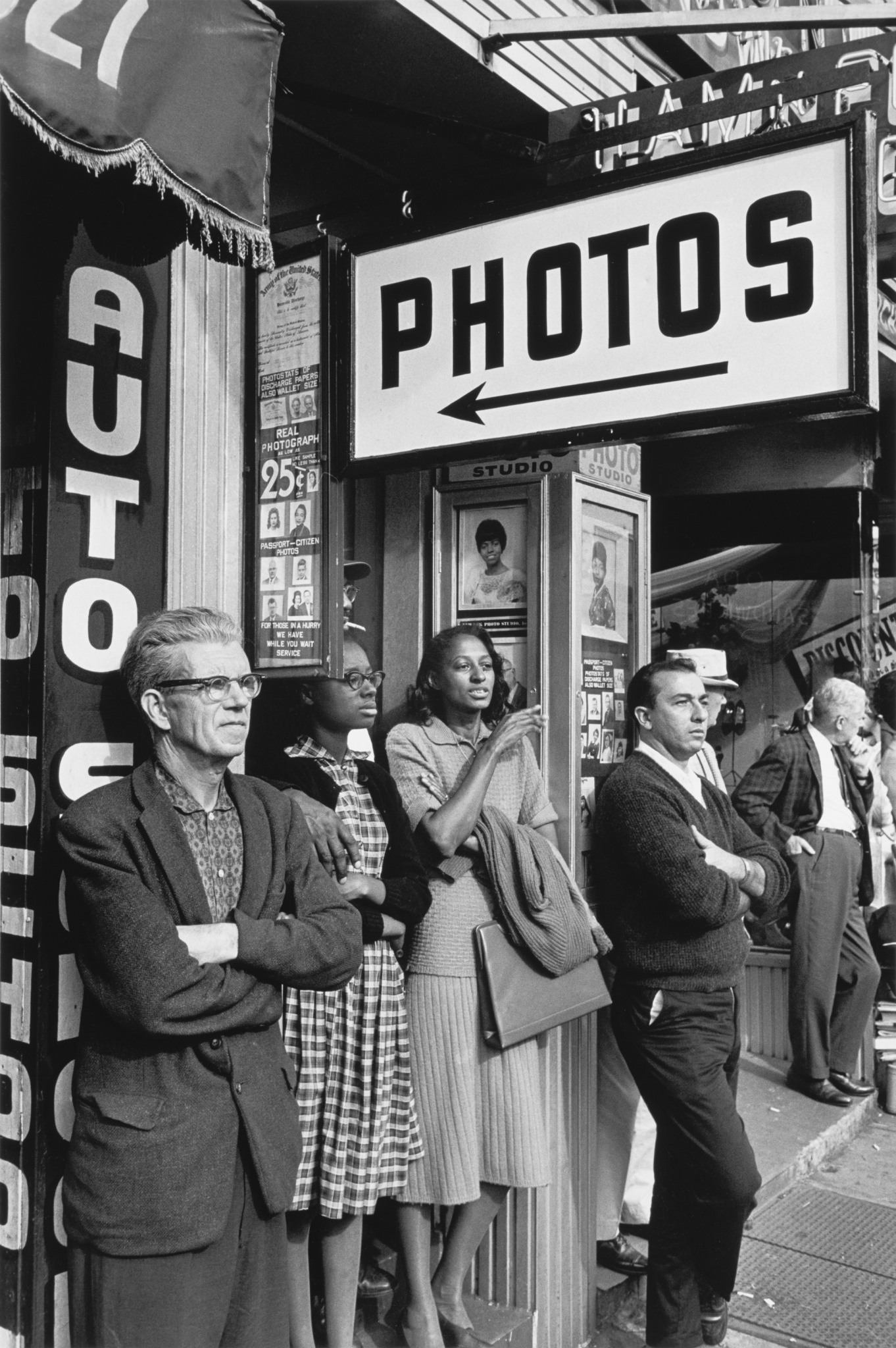

His collection of black and white shots of American billboards, stands, and curios, titled with little more than the place and date ranging from 1962 to 1989, is certainly not the work of an idiot. With instinctive, almost gleeful detail, you take an image like Newark, New Jersey, 1962 and Friedlander slaps you with three details. There’s the composition: the splitting of foregrounds, contrasting paisley and chequered textures, then the relaxed human bodies folded under an arrow slanting nowhere. There’s their naturalism, their lack of eye contact, a single woman engaged, almost smoking, she’s talking so fast. One gets the feeling Friedlander is hardly seen. Is hardly observable when he snaps. Invisible. And what’s wrapped these figures together so perfectly? An advert for photos.

Newark, 1962

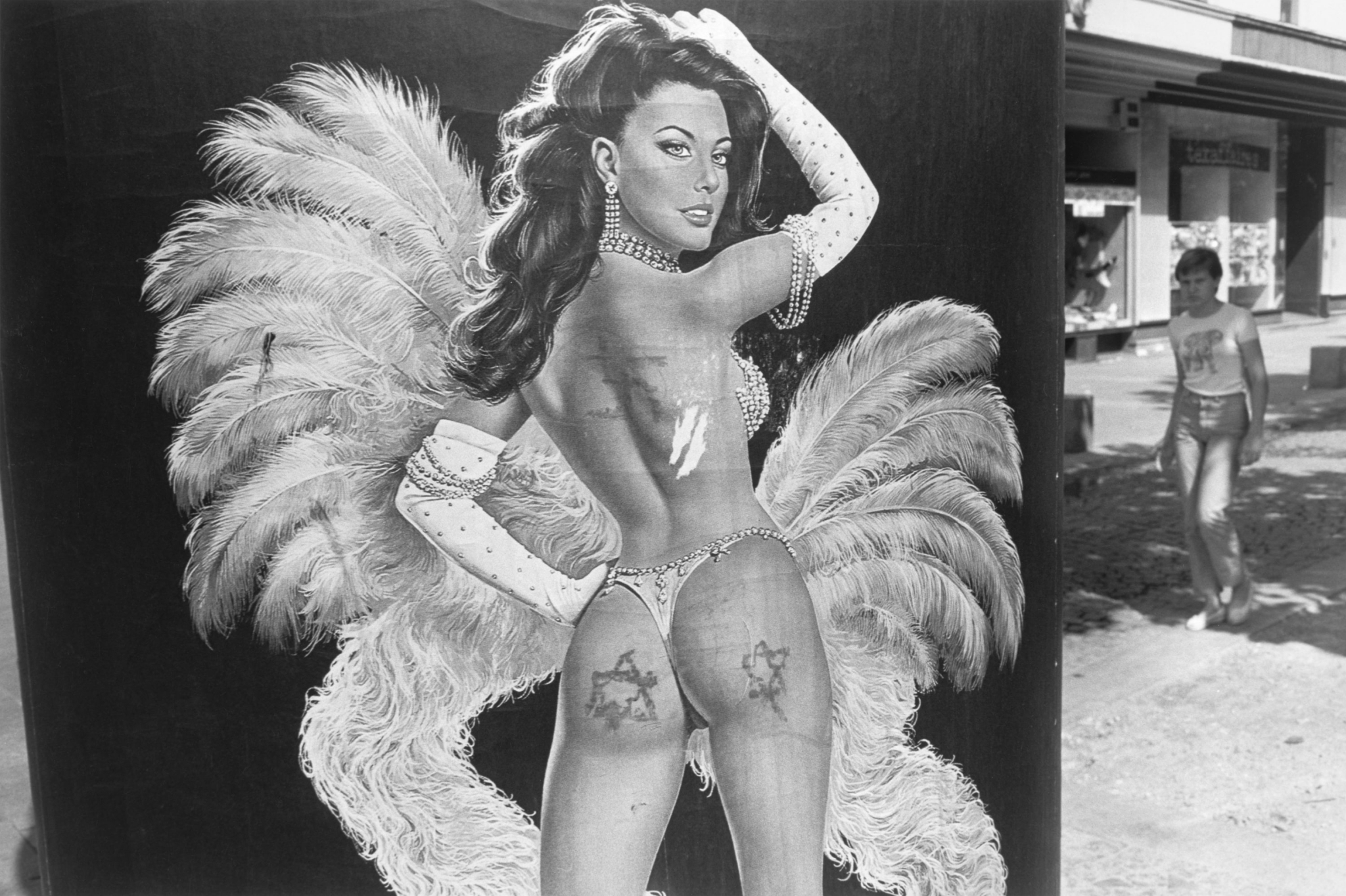

America is a commercial soul, even half a century ago. Friedlander loves that landscape of signs, a place where adverts can become a command. Even, like in Arkansas, 1961, when they become so ineffective they’re meaninglessly funny. Drapes fall over a boarded-up shop window like curtains, the glass just another commercial, and the word ‘FURNITURE’ layered over newspaper rags. Advertisements within advertisements, pointing at nothing. WILD IN THE COUNTRY flashes beneath it. It’s the only label for such a grand failure.

Colours are the great shortcut of the adman but here, in black and white, Friedlander untangles America’s signs with such a clear, almost surgical, fondness. Even if you’ve never seen them, it’s hard not to be nostalgic for the hand-painted messages. Like the same simple words painted across the window in Newhaven, Connecticut, 1980, who couldn’t want that kind of pizza? So then why is it so creepy, so unnerving, when we see SIGNS again, this time written in a shadowy car in Florida, 1963? It can’t just be proximity to Florida that triggers the heebie jeebies. It has to be the off-kilter cursive lettering. The triangular background. The very fact that the sign for signs feels like a bad omen. Something ugly. Too obvious. Wrong.

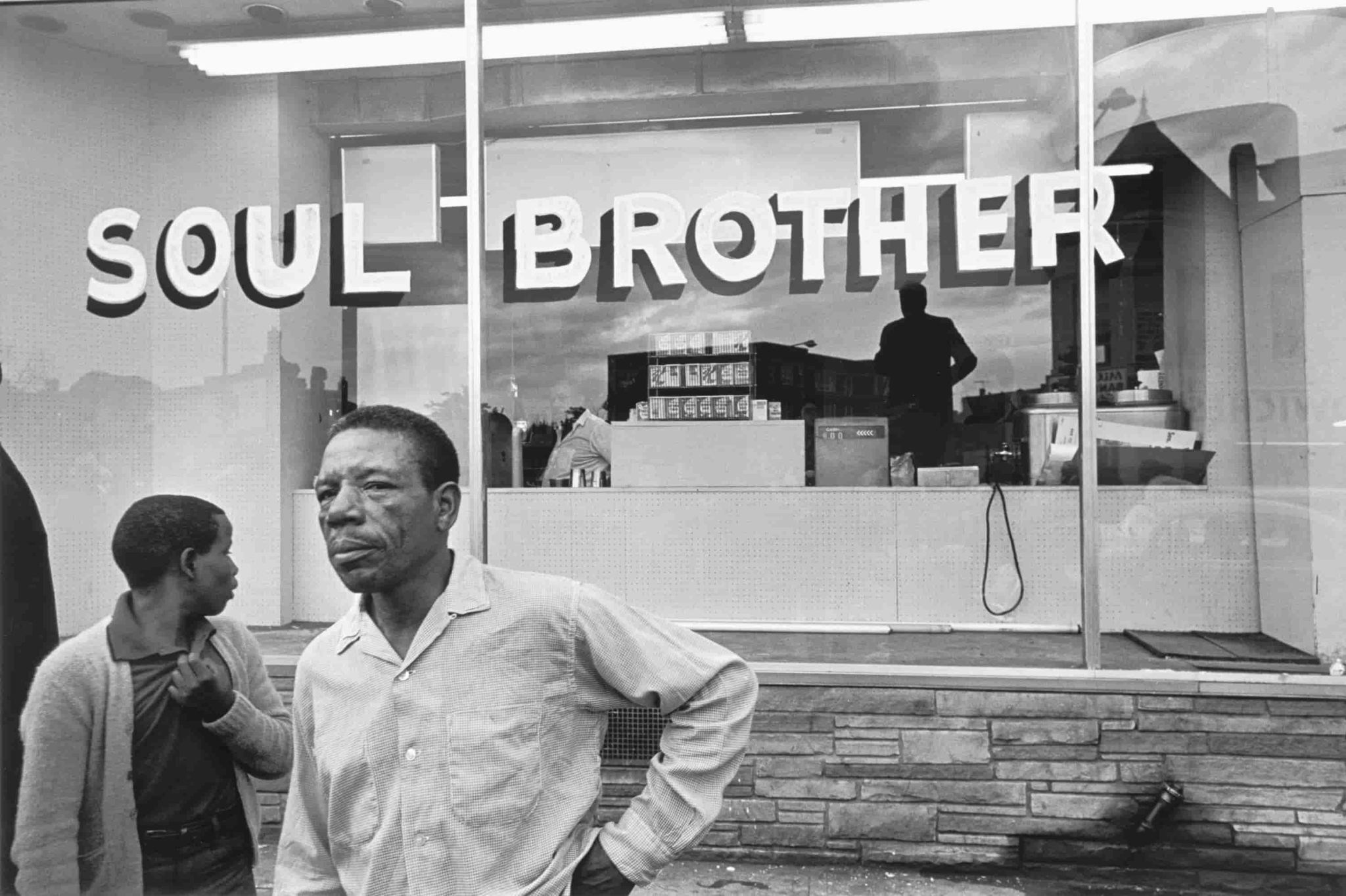

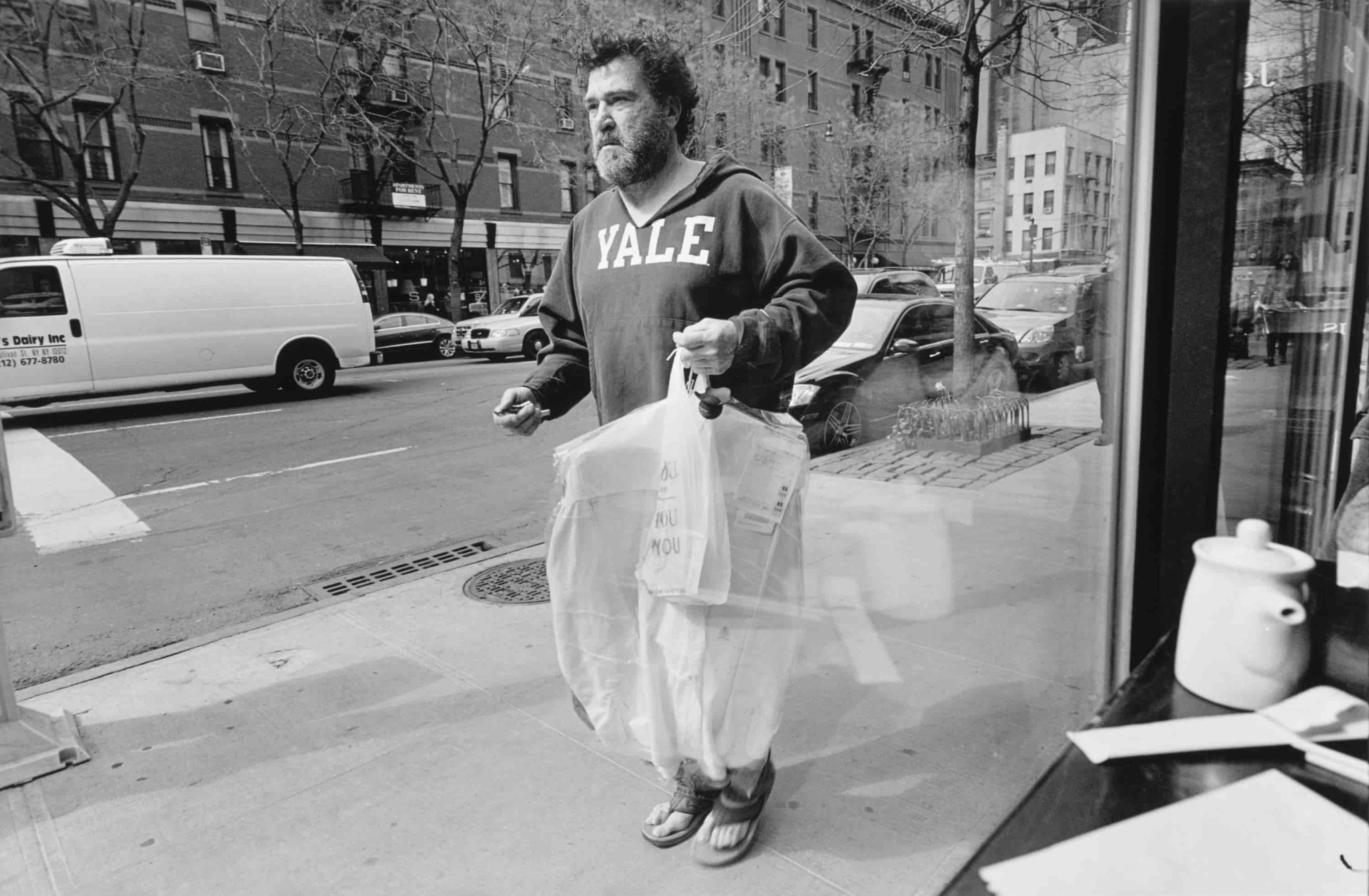

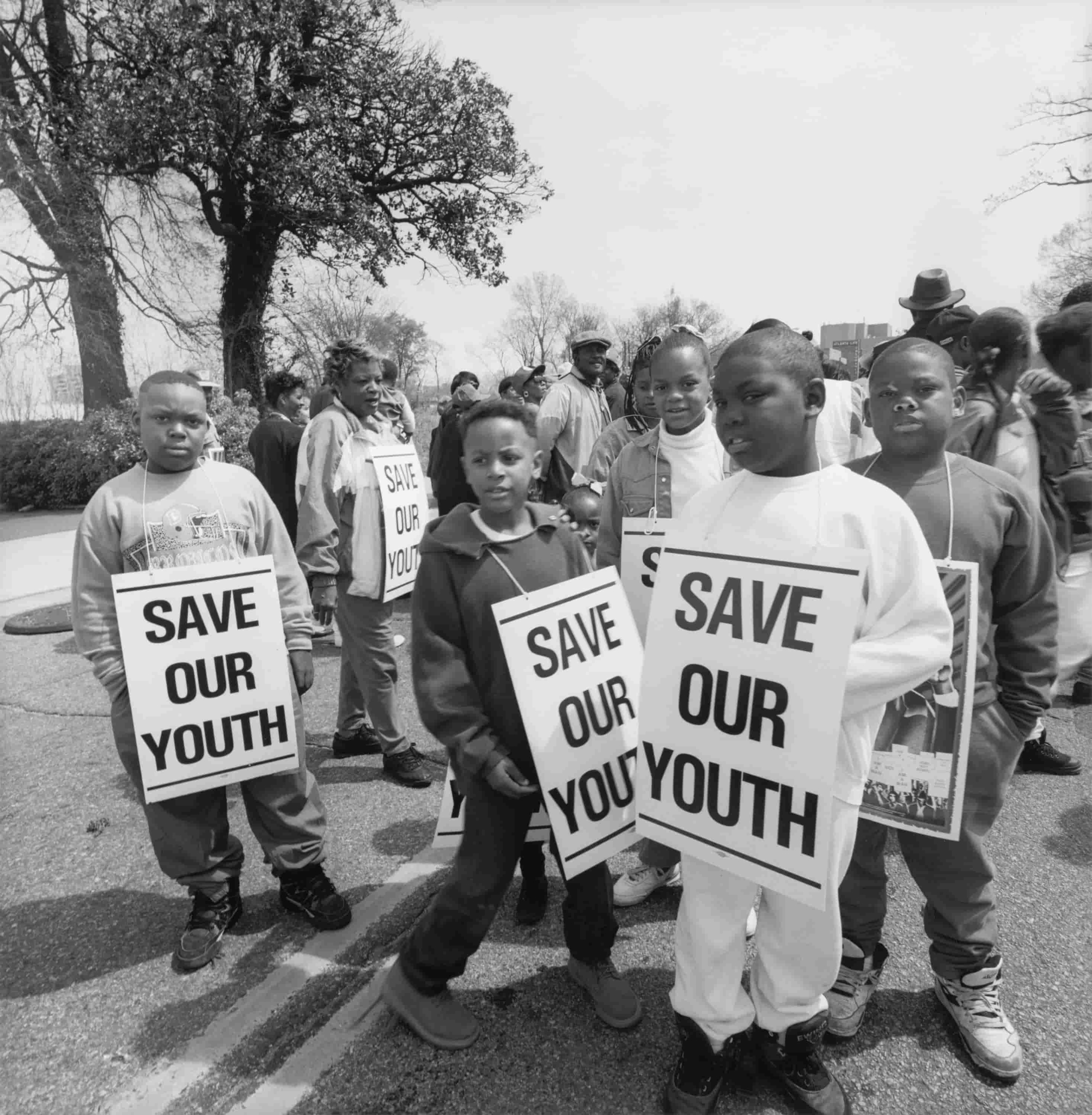

People exist within and around Friedlander’s signs. They are shaped by it, they are amused by it. They are framed by it.

Friedlander is never removed from his photographs. He is always reacting to this world. Rapid City, South Dakota (1969) sees his car at a desert end with a stop sign. Framed in the rear mirror, Friedlander’s watery eyes are as reptilian as the dinosaur blocked out ahead. You can feel the sun there. The heat. I don’t think for a second Friedlander obeyed that sign’s command. But I do think that was his best shot that day.

And I can’t imagine Friedlander, in Nashville, 1968, ever ignoring that little window with Soul Brother as he walked past. He’s in that photo too: another black silhouette on the window. People exist within and around Friedlander’s signs. They are shaped by it, they are amused by it. They are framed by it.

Footnote

The Fraenkel Gallery published Lee Friedlander: SIGNS, a 112-page hardcover book collecting 144 photographs made in New York and other places across the USA, and features self-portraits, street photographs, and work from series including The American Monument and America by Car, among others. Illegible or plainspoken, crude or whimsical, Friedlander’s signs are an unselfconscious portrait of modern life.