What does Brazil’s greatest living filmmaker—and the man behind the groundbreaking City of God (2002)—think of the state of the world today?

Fernando Meirelles represents a nation. When we discuss the living greats of Brazilian cinema, Meirelles’s name comes up first, often followed by his masterpiece City of God (2002). It changed Brazilian cinema, rejuvenated it, reshaped what locals and non-locals thought they knew about the country, stylised and provoked and took him from a successful commercial director into a leading voice of the glorious Resumption movement that included Karim Aïnouz and Walter Salles.

Originating from a farming family, he has a sanctuary (or several) dotted throughout Brazil—grand, private farms which he leaves for time-to-time in the search of normalcy and a connection to the earth. Each month, Meirelles will disappear to one of his farms near Sao Paulo. There, he exchanges his cosmopolitan filmmaker’s life for that of the soil. The environment matters to Meirelles. His dream project, which we discuss, revolves around it. We also speak about his foray into politics.

Somewhere in London, I met Fernando Meirelles. It wasn’t his sanctuary—far from it—but as he was leaving for Brazil that day, I knew that it wouldn’t be much longer until he was.

“To be a Brazilian director is to master the lack of having a method.”

Fernando Meirelles

Chris Cotonou: I was told you have a ranch that you spend much of your time on.

Fernando Meirelles: For generations, my family have been farmers and continue to be. So I also had to have a ranch. I produce avocados, coconuts, coffee, and chilis.

CC: Can you describe that transition between a globe-trotting life in the film industry to solitude on your farm?

FM: It balances me. Every month, I go and stay there for five days. What I like about farms is that they present unique conversations and different challenges. Last time, we had problems with irrigation and my tractor, and so when I arrive I’m dealing with problems that are separate from my other life. I get to become another person.

I think today, I’m better at slowing down. I’m constantly working and now I’m allowing myself days without emails. For those five days each month, my focus is on the farm. I am disconnected. There is a stream with a forest on either side. I created a nursery with a variety of different trees. Every year, I plant 5,000 to 10,000 trees—my company is carbon neutral. My main concern right now is climate change and I’m pessimistic about our future. This is a way to be part of the solution, not the problem. Whenever I fly somewhere I calculate how many trees the journey costs, and I plant the same amount and more. So from this trip, I will need to plant at least three.

CC: How long have you been concerned about the climate?

FM: I’ve always liked trees. In 2004, I started planting a little woodland and then I got involved with seed clubs in Brazil, where we exchange and collect regional seeds. Being a part of this community, I formed a deeper appreciation for the diversity of nature. In a single acre in Brazil, you can have 600 species. While developing a tree nursery, I got introduced to people working to combat deforestation in the Amazon and I got very involved—so much that I helped Marina Silva, Minister of the Environment and Climate Change in her first presidential campaign. It was amazing. Nobody knew her and for a moment she was leading in the polls. So it goes to show how much the environment matters to people.

CC: You directed the Rio Olympics opening ceremony, which had a sustainable angle.

FM: Yes. All the athletes came out holding a tree and each one planted a seed in a little container. This wasn’t a gimmick. Now there’s a wood called the Athlete’s Park, which is all the seeds from the competitors that have now grown.

CC: Most of your cinema observes different facets of politics, whether it’s religion or social problems. Have you considered translating your interest in the environment to the big screen?

FM: I’ve been trying to make a film around these themes since 2019. I have the script. Netflix was behind it and they were prepared to finance everything. Then their stocks fell for a brief period around the pandemic and a number of films had to be cut. We were ready to start shooting, but sadly my film had to be halted. Since then, I’ve been trying to rewrite the script. I still want it to happen.

CC: What is the film about?

FM: It’s a teen movie on the climate crisis. The concept is that if you’re 15 years old and you pay attention to the world, you probably feel as though you have no future. When I started in 2019, it was Greta Thunberg leading the charge and climate change felt like a major threat. But now, because democracies are imploding, it is as though the conversation has moved on. AI will take over jobs. So the film is, in some ways, what it means to be a teenager looking ahead. In the 1960s and 70s, when I was young, everyone felt like we could change the world. Now I see young people deflated. No one has a cause anymore.

CC: They can’t imagine a better world.

FM: Right. It’s dominated by Big Tech. We’re living in what I call the Post-Legal era. Look at the way nations are operating. There’s no reason to respect legal agreements—look at Israel, for example. So it feels like the time to create a film that revolves around our Post-Legal era. I own several farms and at one of them I’m creating a structure in case everything collapses—solar power, so I can have my own electricity; and my own water and food.

CC: You’re preparing for a great catastrophe.

FM: I think civilization might collapse in 15 years. Look at climate change—there’s no way back. Perhaps Costa Rica is the only country that does things right. They have no army, they care for their nature…

“I think civilization might collapse in 15 years.”

Fernando Meirelles

CC: Talking of politics, do you find it harder to screen your work in Brazil depending on who is in power?

FM: It’s never easy, but I didn’t have a problem during Bolsonaro. I was shooting a TV series in the US—I have a company that produces and he cut the funding across the industry. Brazil was producing 100 features a year and under Bolsonaro, it went down to perhaps 20. Then it went up again with Lula. Regarding censorship or freedom of speech, I can make anything in Brazil, but I can’t be sure I’ll have it financed. It comes off something Wagner Moura recently told a colleague of mine: that the success of Brazilian cinema is defined by who is in power. It’s highly funded by state money. Right now, it’s a great time for Brazilian cinema.

CC: What would you like for the future of Brazilian cinema?

FM: I see a lot of good young filmmakers now. There are also far more film schools than when I was a student. We’re experiencing a bit of a moment right now. There was a wave a few years ago, but it didn’t manage to remain consistent. Now Brazilian filmmakers are making great second films instead of popular one-off films.

CC: Do you see yourself as a Brazilian director with a Brazilian voice?

FM: Yes. Because I carry the perspective of an outsider. When I made The Constant Gardener (2005), John le Carré told me that with a British director, it would be a very different film. He saw that I applied the vision of an outsider. I always project with my South American perspective.

CC: What does it mean to have a South American perspective?

FM: You Westerners only look to yourselves and you don’t understand the rest of the world. We from the so-called third world understand clearly how it works—with corruption and hypocrisy. So my lead characters from my ecological film are outsiders. They are from the six billion plus who make up the world beyond the US and Europe.

CC: Do you care about the attention of the American industry anymore?

FM: I never wanted it. I came to the international market by total accident because I decided to make this film called City of God (2002).

CC: City of God is considered one of the greatest movies of this century.

FM: It was supposed to be a low-key Brazilian film with unknown actors, by an unknown director. It was financed by myself and the money I’d made on commercials. There were no expectations to sell it abroad. But I showed City of God to Canal Plus in France and they bought it on the spot and put it into the Cannes selection. But Walter Salles, one of the producers, made the jury so it had to be Out of Competition. It played so successfully, I returned to Brazil with 17 script offers. It never occurred to me to make an international film—especially my first feature.

CC: Who was that film made for?

FM: I made it for Brazil and the Brazilian people. At the time, I was looking for something to shoot. A friend offered me the book and told me how it would make a great film. But I said: “I’m never going to make a movie in the favelas because I don’t know that world, it’s not my world.” But as I was reading the book, I was annotating it with filmmaking prompts and by the end, I had the movie planned out. It shocked me. I couldn’t believe this was the reality of Brazil—that in Rio de Janeiro, there’s a lawless place with different rules. I called the writer and we agreed that it could be adapted. I made City of God to show the realities of the favelas to Brazilian people—especially the middle class. This is us.

CC: How do you find that balance—especially as an outsider?

FM: The trick was: the perspective of the film would come from the inside. That was my biggest mission. Because what we hear—especially us white people—about favelas is told by press people from the outside. The story was written by Paulo Lins, who was a writer from inside. That’s very rare in Brazil, particularly back then, so we stayed true to that perspective.

CC: How did you gain access to the favelas?

FM: Paul helped me. I went with him to the City of God and he introduced me to the right people. We presented my production team and we cut a deal with everyone. But we shot in a different place [Cidade Alta]. When you speak with the right people, you don’t have a problem. Besides, I find it easy to connect and form relationships with people from different backgrounds. What interests me are differences. I want to be challenged. If I believe something and someone proves me wrong, I love that. It’s important to listen and see from new perspectives. I have friends—real friends—who are incredibly poor. We come from different worlds but we understand each other.

CC: Can you tell me about your filmmaking? How much planning do you do?

FM: To be a Brazilian director is to master the lack of having a method. I don’t like to storyboard—unlike Hitchcock, for example. I don’t plan. My filmmaking is like jazz—I’m a jazz director. Let’s shoot the actors and let them play. I improvise. I observe the scene like a theatre production. Everything is thought out in the moment, on the day, and adapted to the environment.

CC: So you enjoy making life harder for yourself.

FM: [Laughs] I wouldn’t say that. I enjoy the action.

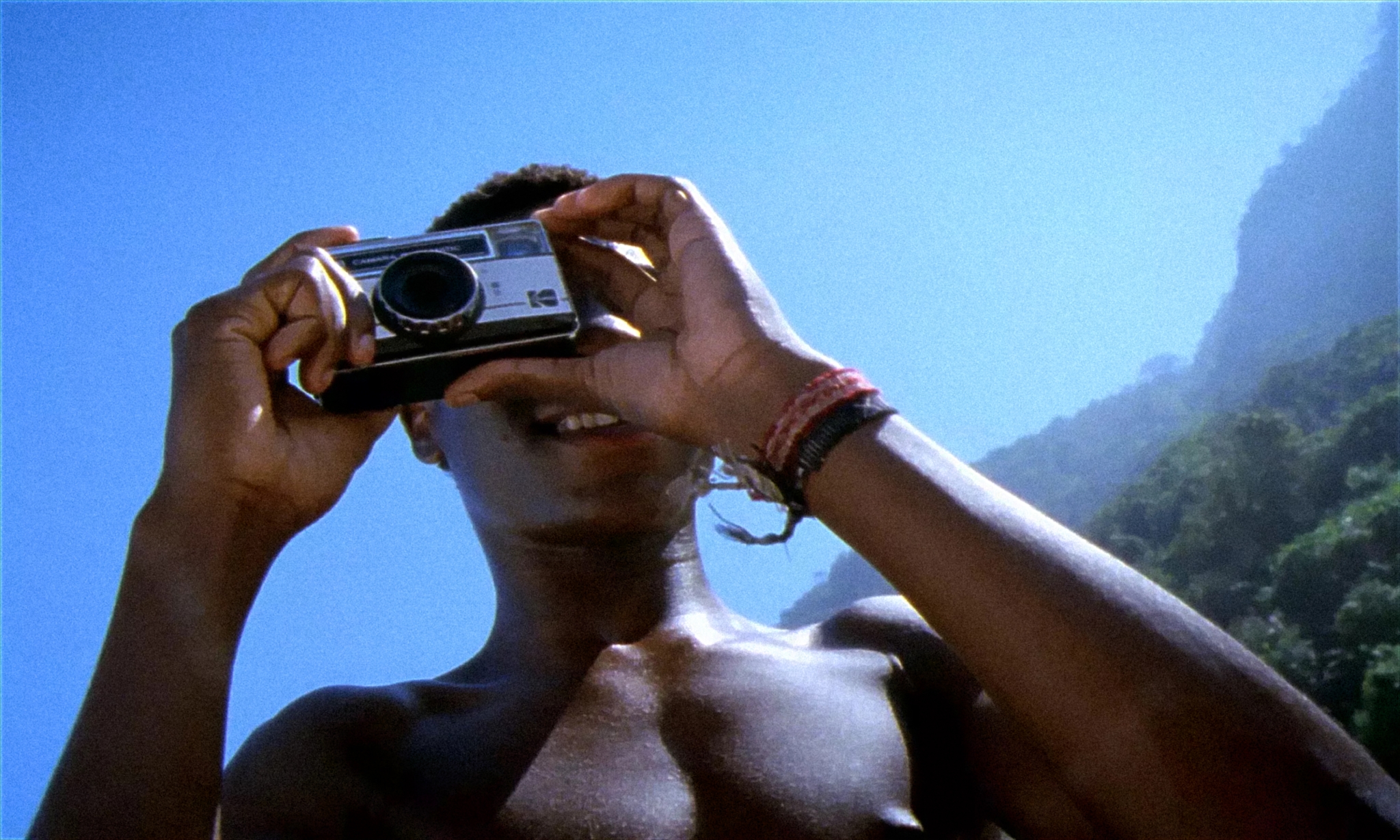

Still from City of God (dir. Fernando Meirelles, 2002)

CC: Considering there were no expectations with City of God, was it the most pleasurable experience of your career?

FM: It was. I tried to sell it, but everybody told me it would be a flop. Because I financed it, I could do whatever I wanted. I didn’t have to show my dailies to anybody. It was one of the best experiences.

When you work with streamers you get pages of notes from producers and they try to offer advice. Sometimes it’s good advice, but you have to negotiate.

CC: One of the standout roles is Seu Jorge, who is today known as one of the biggest stars in Brazilian music.

FM: Yes, but he wasn’t at the time. It’s a funny story. I was rehearsing his part with another great actor, now director, called Lázaro Ramos. Jorge was rehearsing the lead role in Madame Satã by Karim Aïnouz, who was also going to Cannes. We started shooting on the same day. But Karim came to me with a problem: Jorge was playing Madame Satã, who was gay. And he wasn’t comfortable performing in some of the sex scenes. Could I give him Ramos in exchange for Jorge? I was surprised Jorge was open to joining me as a supporting actor instead of the lead.

CC: I’ve heard conflicting opinions on your Catholicism.

FM: I am not a Catholic. If anything, I’m anti-Catholic.

CC: The Two Popes isn’t a Catholic story?

FM: No, and that’s a big misunderstanding. It’s about two men forgiving each other, trying to redeem themselves. In some ways, it’s about Pope Francis—not because he was religious, but because he was a contemporary man. I agreed with his perspectives on many things, including the environment and society, but not his God. When I was offered the film, I wanted to explore this contradiction.

CC: You’re considered a legend in Brazil today—greatly respected by emerging filmmakers. Do you recognise that at all?

FM: I think I’m respected. I know that I have a loud voice in Brazil, louder than many. But today, it’s smaller than you think. Of course, I did the Olympics, and I also directed an opera in the country. I do as much as I can there. And I continue to support talent: if you look at my IMDB and my production company, it’s an endless list. Sometimes people just need my name attached to projects to get financed. Other times, there’s advice. It’s a part of our job to help others; to nourish the next generation.

CC: Where does this natural empathy come from?

FM: I think I know. I have this memory that stays with me.

I was seven. My family had this farm near São Paulo. There was a big house, filled with my cousins and relatives—sometimes 20 people. We would have dinner and then go for a walk, following an old railroad track that ran through the farm. We would go up the mountain and then return. But one night, I let everyone go ahead of me. Alone, I lay down and looked up at the sky and had an epiphany. I saw how beautiful the sky was, surrounded by all the stars. And I felt its significance and how small I was in the universe. I thought: who am I? I’m less than nothing.

From that point on, I became afraid of death. It has been this way my whole life. I think about my mortality every day. But over time, it helped me understand life and living with the presence of my own limitations. Nothing matters, and that’s fine.

CC: But if nothing matters, why are you so conscious of preserving the environment?

FM: Why not make existence better for as many people as possible before we leave?

CC: Are you spiritual at all?

FM: I was curious about this for a while. There is something. What I don’t believe is that God is a consciousness we speak with. I find this ridiculous. The Bible is a crazy book written by a man. By the way, that’s a film I’d love to make: about the craziness of religion. You see the war between Iran and Israel, and both are acting on behalf of God. It makes no sense. Compared to what they believe, Donald Trump is a scientist.

CC: What would your religious film be about?

FM: Maybe it would be about ayahuasca. I’ve taken it before, and you do feel as though you’re part of the universe, that there’s a connection. So maybe religion, in this sense, makes sense. [The philosopher] Baruch Spinoza’s God is interesting: it’s not a consciousness. Nature has rules that apply not only to this planet or galaxy. Nobody is checking us.

CC: Sounds quite encouraging.

FM: Carpe diem. This is a good thing. Enjoy it.