Louisa Guinness discusses the exhibition, which reconsiders the surrealists not only as artists but as alchemists of desire.

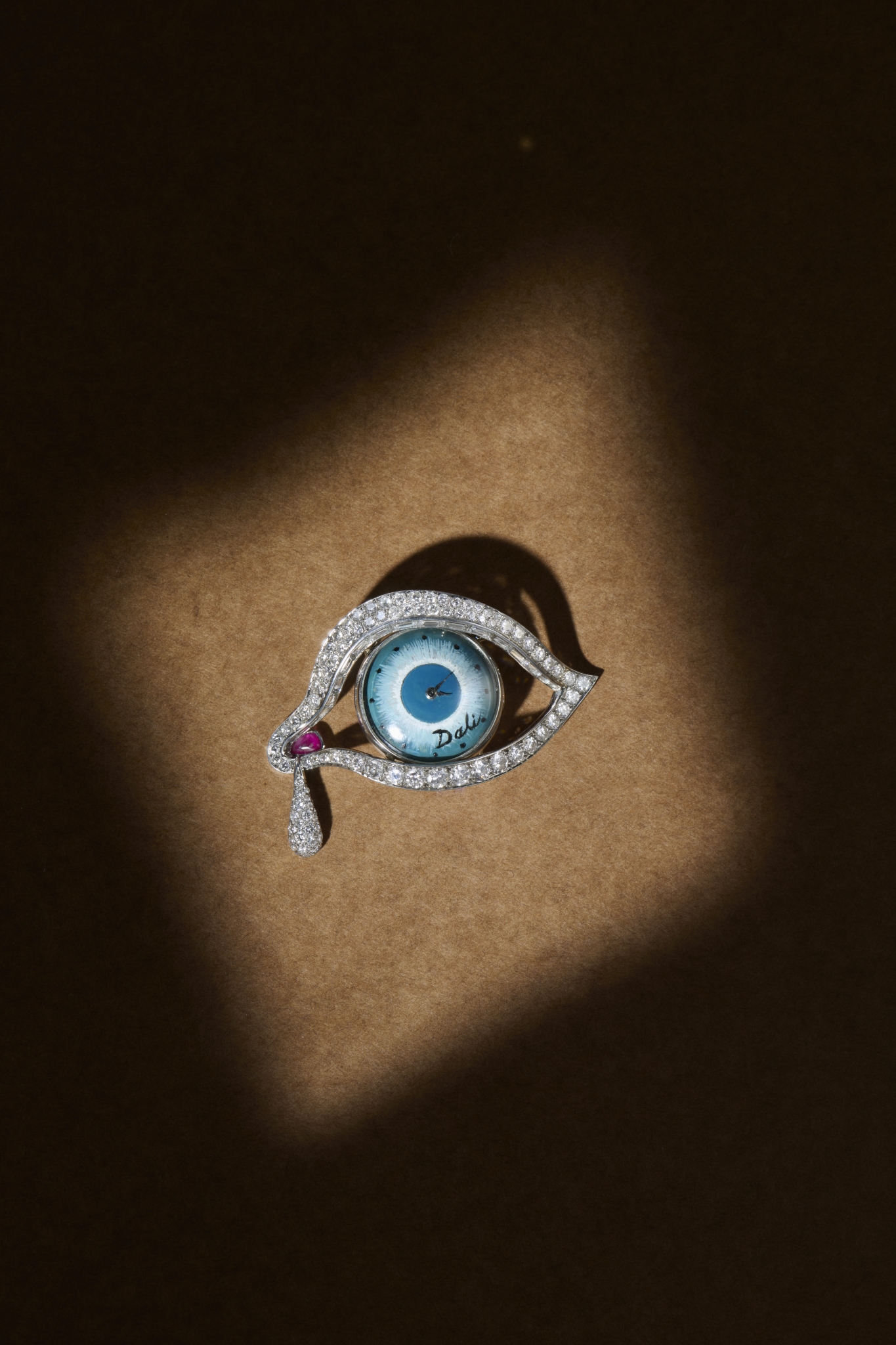

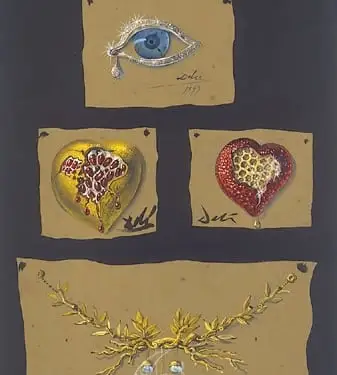

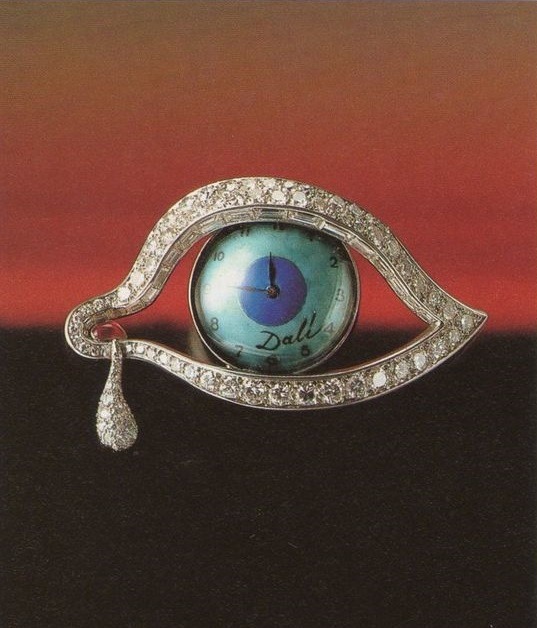

Salvador Dalí believed that jewellery should outlast its wearer—that beauty, if rendered marvellously, could defy time. His Eye of Time, created in 1949, is proof: a working clock encircled by platinum lashes, its ruby pupil gazing toward eternity. This week, the eye returns to London for the first time in four decades for Surrealist Jewels 101 at the Louisa Guinness Gallery—an exhibition that reconsiders the surrealists not only as artists but as alchemists of desire.

Three years ago, I bought a book on Dalí’s jewels at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris (the one with this very blinking eye on the cover). I still return to it often; it is a small totem of everything I love about the surreal and a glimpse into a part of Dalí’s world that remains less explored. As a self-confessed jewellery aficionado, I find myself drawn to the histories that sparkle beneath the surface, so this exhibition felt entirely my cup of tea.

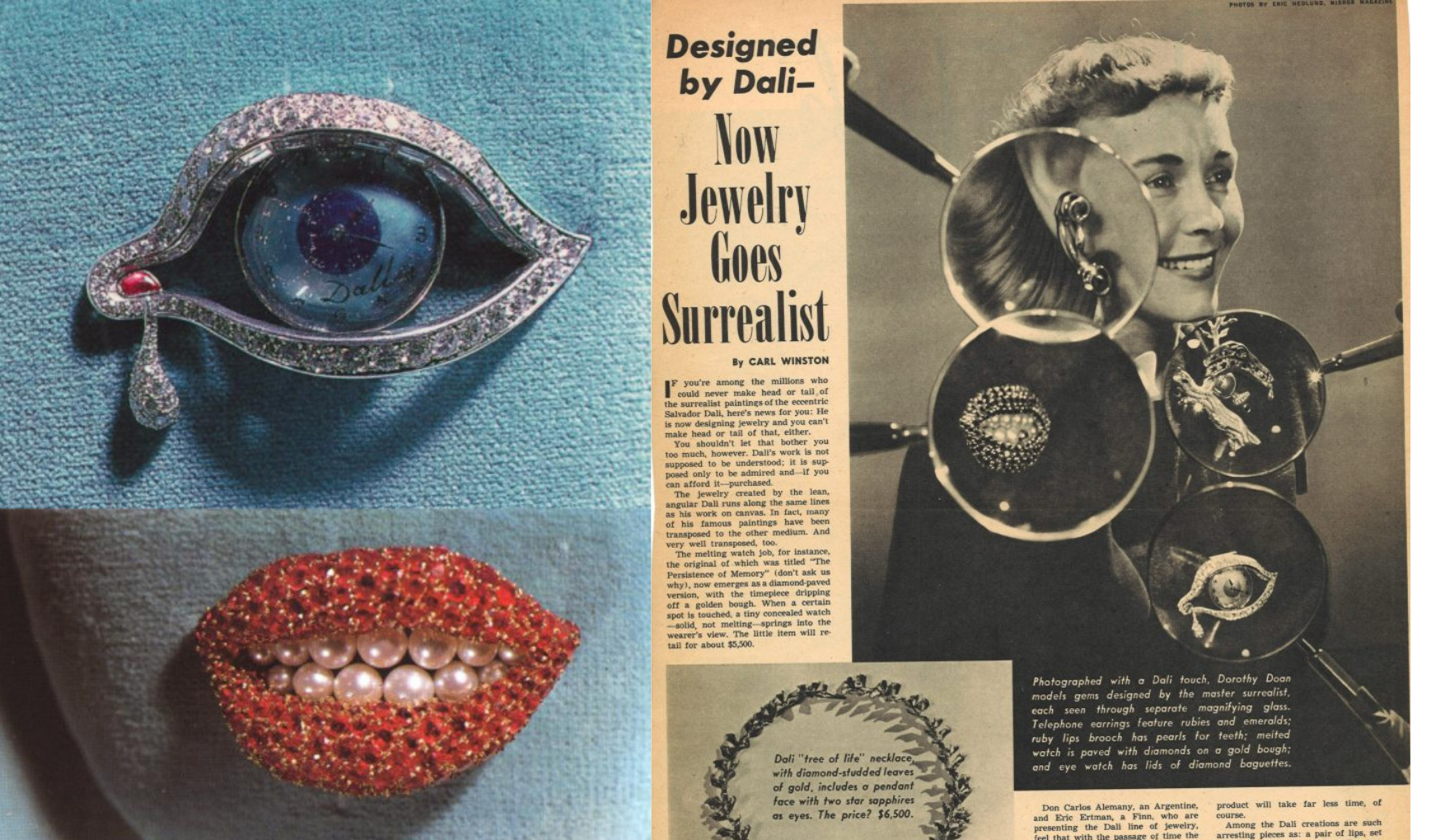

I brought the book with me to show Louisa, who, to my delight, had the very same one on her desk. In that moment, surrounded by vitrines of ruby lips, golden hearts, and mechanical eyes, I felt I’d met a kindred spirit—someone who shared my fascination with both art and ornament, with surrealism as something you could live with and wear.

“Everyone did surrealism last year. I thought 101 felt more fitting; a little stranger and a little more surreal. That’s the point, isn’t it?”

Louisa Guinness

Louisa Guinness, who has championed and pioneered the field of artist jewellery for more than two decades, spoke about her decision to celebrate 101 years of surrealism rather than one hundred. “Everyone did surrealism last year,” she said, smiling. “I thought 101 felt more fitting—a little stranger and a little more surreal. That’s the point, isn’t it?”

The exhibition at the Louisa Guinness Gallery on Kensington Church Street gathers a cast of artists who turned imagination into object: Dalí, Man Ray, Niki de Saint Phalle, Claude Lalanne, César, Leonora Carrington, Max Ernst. Each piece captures the essence of the movement in miniature. Louisa’s gallery has long been a home for these works. “I started with artist-designed furniture,” she told me. “Then one Christmas, I decided to do a jewellery show. I collected Picasso, Max Ernst, and realised I needed something contemporary, so I began commissioning artists myself. No one else was doing it.”

Dalí’s Eye of Time, realised by the Argentine goldsmith Carlos Alemany, embodies that spirit. Dalí once described his jewels as “a protest against emphasis upon the cost of materials,” valuing design and craftsmanship above carat and cost. “My art encompasses physics, mathematics, architecture, nuclear science, the psycho-nuclear, the mystico-nuclear, and jewellery, not paint alone,” he wrote in his 1959 catalogue Dalí: A Study of His Art-in-Jewels.

His creations were rich in symbolism: rubies for energy, sapphires for tranquillity, lapis lazuli for the subconscious mind. The Ruby Lips brooch, inspired by Mae West’s come-hither smile, glitters with pearl teeth and Dalí’s characteristic humour. Before working with Alemany, Dalí collaborated with Duke Fulco di Verdura, the Sicilian jeweller who made his name designing for Coco Chanel. Their 1941 Medusa brooch, a tangle of gold snakes with ruby eyes, debuted at Julien Levy Gallery before landing at MoMA.

“What excites me is when artists take risks. When they’re unapologetic. That’s what surrealism always was, a rebellion against reason.”

Louisa Guinness

By the 1950s, Dalí’s designs had grown ever more intricate: a pulsing ruby heart, a mechanical flower with diamond “pears” that opened and closed, a fully articulated starfish that wrapped around the wearer’s arm. These works blurred the line between art, performance, and anatomy.

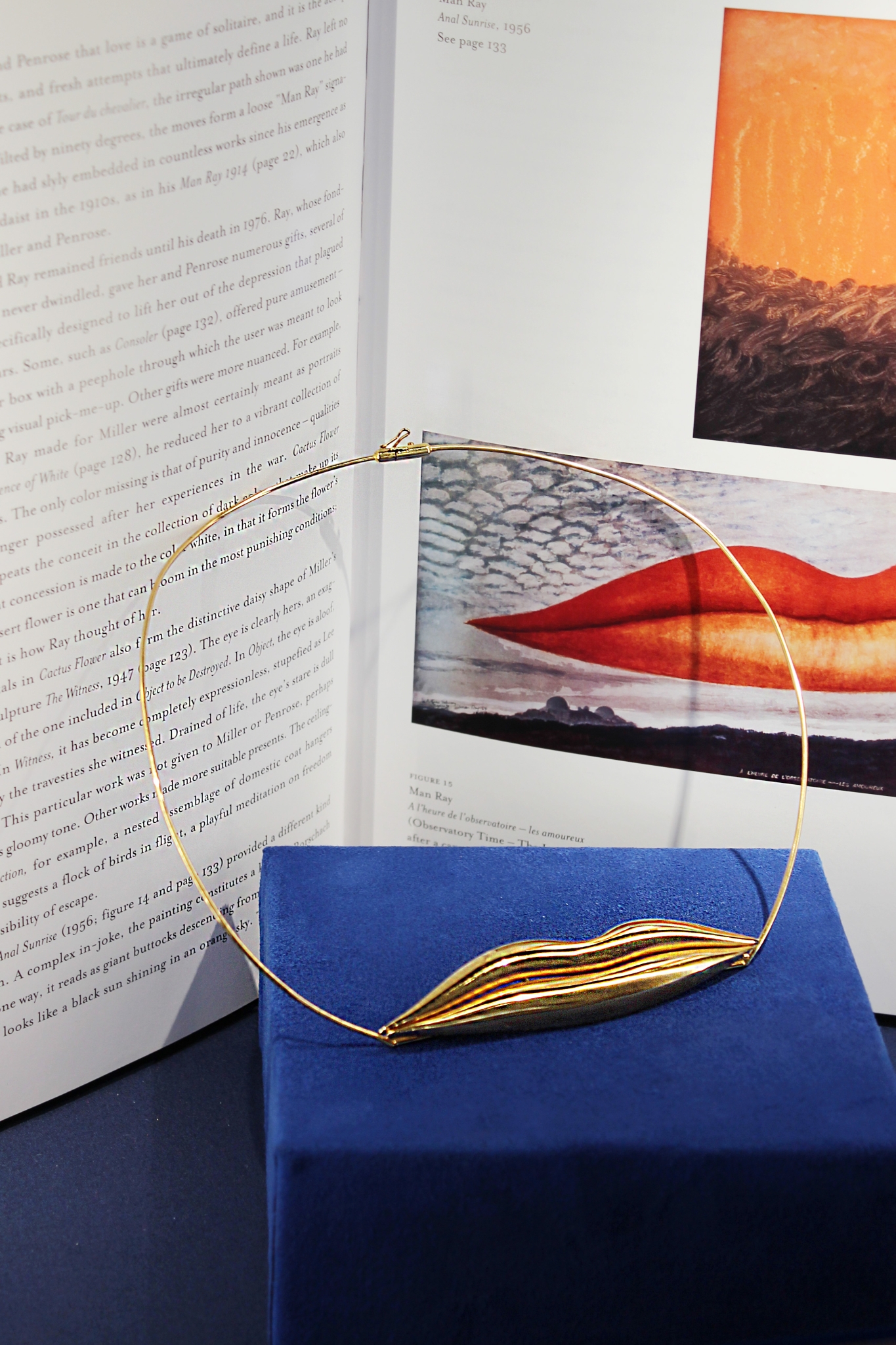

Louisa and I talked more, and she began to tell me stories—fragments of history that have lived in her world for years. We talked about the talented Gian Carlo Montebello, a dear friend of Louisa’s, who had worked with Man Ray and Niki de Saint Phalle. “He must have done about fifty collaborations,” she said. “Then one day there was a burglary. Everything was taken. And he stopped. Just like that.” That fragility runs through the history of artist jewellery: objects both eternal and ephemeral, born of singular visions and human hands. It is a privilege to see all of these incredible works under one roof. Lalanne’s Collier Ronce winds around the wearer’s throat like a living branch. Niki de Saint Phalle’s Nana pieces pulse with enamel and exuberance. I’ve long admired her fearless femininity; to see it rendered at such an intimate scale felt like encountering an old friend in a new guise.

Halfway through our conversation, Louisa produced a selection of Magritte-style bowler hats. “You can’t talk about surrealism without a bit of theatre,” she laughed, and I obliged, putting on the hat with butterflies while Louisa donned one with doves. There were only three of us: Louisa, myself, and my dear friend Aloisia Rucellai who does, in fact, have photographic evidence of this (though I shall not be sharing it). Laughing in our hats among vitrines of ruby lips and violin brooches, for a moment the gallery itself felt like a dream set in motion.

Today, Louisa continues to support new voices alongside the masters. Jiayang He’s trompe-l’œil enamel rings, painted to mimic gemstones, deceive the eye entirely. Hannah Martin’s sculptural pieces explore sensuality and structure, while Veronica Fabian’s woven silver chains reinterpret the language of adornment. “What excites me,” Louisa said, “is when artists take risks. When they’re unapologetic. That’s what surrealism always was: a rebellion against reason.”

Perhaps that is what jewellery represents, too: a rebellion against utility. Dalí once wrote that his pieces would prove to history “that objects of pure beauty, without utility but executed marvellously, were appreciated in a time when the primary emphasis appeared to be upon the utilitarian and the material.” Louisa, like Dalí, understands that paradox — and revels in it.

I could have stayed there for hours, listening to Louisa’s stories and flipping through the pages of her seemingly endless array of reference books. We spoke about how jewellery speaks to us—how it holds memory, and how it brings art into life. Upon leaving the gallery, the world outside felt a little less ordinary, as if the surreal had followed me out onto Kensington Church Street.

Surrealist Jewels 101 runs at Louisa Guinness Gallery, 45 Kensington Church Street, London W8 4BB, through 7th November 2025, a fleeting vision of the surreal that would be a tragedy to miss.