As One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson’s anticipated adaptation of Vineland hits cinemas, Sam Murphy argues that Thomas Pynchon’s paranoid vision is more relevant than ever.

It’s hard to be famous in America. It’s harder to remain invisible while successfully chronicling it. But Thomas Pynchon, the award-winning post-modernist writer has a knack for it. At almost 90 years old, the most recent known photo of Pynchon is at eighteen, from his time in the Navy in the early Cold War. His dark hair is ruffled under a sailor’s cap. His eyes catch the light. He is grinning—despite the military document—and his two enormous buckteeth flash back like daggers too big to fit into print.

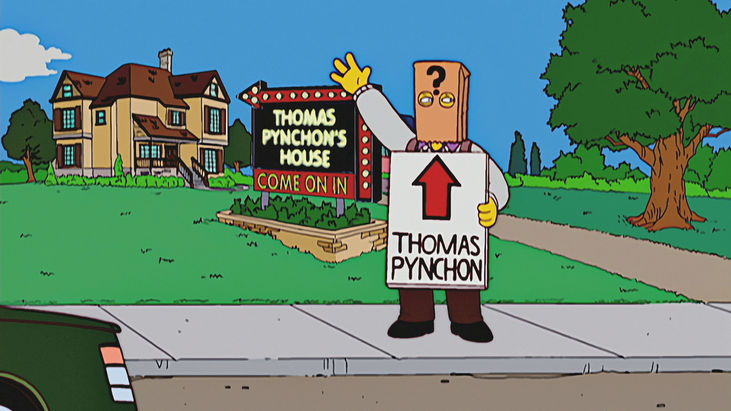

For an enigma, it’s fitting that Pynchon has a smile like a cartoon. Despite being alive (allegedly), writing avidly (Shadow Ticket comes out this Oct), nothing beyond three black-and-white photos exists of him. Pynchon, whose middle name, if you’re desperate for details, is Ruggles, has never given an interview. The closest televised appearance he’s come to were two cameos in a vintage Simpsons episode. Pynchon wore a bag over his head. Both times.

Soon to be Paul Thomas Anderson’s second adaptation of Pynchon’s work, (One Battle After Another, following up 2014’s Inherent Vice), Vineland arrives in 1990 at the tail end of Reaganomics, where the dreams of America’s countercultures have filtered into a stoned nightmare. In a small California town, Pynchon’s narrative settles on Zoyd Wheeler, the former hippie who performs an annual stunt—diving through a window—as evidence he’s legally entitled to disability benefits (he is reimagined in One Battle as Bob Ferguson, a washed-up radical played by Leonardo DiCaprio). His daughter, Prairie, now 14, has grown up without her mother, Frenesi Gates, a radical filmmaker who vanished years ago after becoming entangled with the federal prosecutor, Brock Vond (Teyana Taylor and Sean Penn reimagine these roles, and their sexual dynamics, in PTA’s retelling). As Prairie searches for the truth about her mother, Pynchon weaves a cipher of betrayals and radical politics within a network of surveillance stretching back to the 1960s.

Thomas Pynchon in The Simpsons.

The novel moves between timelines. It happens quickly, manically, sometimes impossibly fast, tracing the rise and fall of the People’s Republic of Rock and Roll (PR³), a hippie micro-nation, and the infiltration of its members by Vond and Frenesi as fed-approved double-agents. If the structure sounds confusing, and the book’s insane names seem unserious, they are. Pynchon’s style is a saturation of paranoia. Hazy. Oddly focused. Stoned. Song lyrics are a small love of his, penning their way through the pages and begging to be hummed like this ditty: “High fi-nance, / Is it th’ start of, / Another cheap ro-mance.”

Objects, better than people, define characters: from Zoyd’s first half-opened box of Count Chocula cereal to a passer-by’s Cerutti suit, cufflinks accented with “touch-them-you-die double-soled shoes from someplace offshore, the works.” Vineland is a world of things. A jack-in-the-box of pop-culture. It is toys describing toys.

Pynchon’s Vineland is saturated with anxiety, not just as a mood but as a comic principle. Run-on sentences do the rest, spiraling, dragging you into a mild vertigo as they clamber up to a page in length describing the link between zoot suits and banana republic conspiracies, until you, or any over-saturated drug addict, is out of breath.

After the dense, V-rocket arc of Gravity’s Rainbow, Pynchon’s 1990 follow-up was dismissed by some high-minded critics as a Pynchon-lite pice of pop-culture fluff. But like his goofy style, to mistake Vineland‘s mood as unerringly cheerful is a mistake.

Nothing is ever ‘said’ by a Pynchon character, but whispered, cackled, sometimes just implied by an adverb (Paul Thomas Anderson’s earlier Inherent Vice adaptation of Pynchon employs this often, mumbling the most essential details in the book to keep you pissed off). By the start of Vineland’s second act, Prairie’s search for her mother has led her through mob weddings, a sexually trained ‘ninjette’ assassin who can kill with chakra, and a DEA agent addicted to television. The effect is a catherine wheel of free associations. Pynchon presents the disney-land world version of America; where violence can be an amusement park: a “third-world styled” attraction where you can kill “carefully multiracial [targets] so as to offend everyone”.

From the hippies who won’t eat red vegetables to avoid the colour of anger, all the way to federal forces that lost their left-wing re-education schools due to Reagan-budget cuts (Reagan concluding that children naturally grow out of being communists), every group in Vineland is something half-cooked. But unlike the ‘carefully’ offensive Matt-and-Trey juvenalia of cartoon comedy, truth can be deferred. It’s best found in the paranoid fringes—the skulls of the narcs, the surfers, the bums—the bleeding edge where reality can apparate into Pynchon’s cartoon world with the odd rhythm of a seizure.

Pynchon’s Vineland is saturated with anxiety, not just as a mood but as a comic principle. Run-on sentences do the rest, spiraling, dragging you into a mild vertigo as they clamber up to a page in length describing the link between zoot suits and banana republic conspiracies, until you, or any over-saturated drug addict, is out of breath.

“We are digits in God’s computer,” muses Prairie’s specter of a mother Frenesi, humming the words to herself like a gospel tune by a rainy grocery store window. Like Bowie, Pynchon had an early hunch, by 1990 when the world wide web still required a phoneline, the internet would mean something. In Vineland, 17-years in the making, Pynchon crystalised how an all-seeing eye would be abused.

As Prairie closes in on her mother’s strange erasure and a family reunion comes to light, transcripts from agents with impossible acronyms lurk behind every corner. Pynchon’s old fascination with aerodynamics and V-rockets is switched for the low, the new references, the everyday things that are still abuzz in computers and television. The media stream is perfect for a book’s pop-culture focus so specific that movies like Friday 13th come with exact dates [1980]. Fitting for a writer best known in a Simpson cartoon, we see the obsession in the eyes of federal agent Hector Zuñiga, whose entire worldview is so shaped by the television shows he binges, he’s unable to distinguish his life from a cop show plot. The brain-rot bubbles up again in Brock Vond’s “Tubal Detox” centers, housing dissidents who are forcibly re-educated by an overwhelming barrage of television: brainwashing that pacifies rebellion by replacing it with mindless entertainment. Ring any bells?

When the two timelines collapse and federal forces begin to hunt Prairie to settle an old score, the novel’s critique of media saturation is equally sharp: the fascists, most dangerously in Trump’s White House today, are not men with mustaches and leather suits, but the ones that smile. They are clowns designed to amuse. Their preferred televisual medium now their own personal computer playgrounds, the Tubal Detoxes, or Twitter, now-X, Meta, Truth-Social.

Teyana Taylor and Leonardo Dicaprio in Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another (2025)

Perhaps the reason Pynchon is so enigmatic, and still stubbornly writing novels describing America, is that Vineland reads today like a good warning we failed to heed. In one exchange, a character screams out the Reagan-era impulse to:

“…dismantle the New Deal, reverse the effects of World War II, restore fascism at home and around the world, flee into the past.”

It’s a line that echoes Trump’s weaponised nostalgia. The novel’s vision of a media-saturated public too distracted to resist feels prophetic. And that’s the point: Vineland insists that in America, history is not recovered but rewritten—the very title a faded referent to America’s forgotten christening by Vikings as Vinland.

Underneath the toyshop America parades itself as, memory is a commodity that can be exploited. All the music and camp names in the world won’t change the fact that the surveillance state doesn’t just watch—it narrates, edits, then erases. Even celluloid, for Pynchon, can be an act of murder. And when the young man, after giving out to his Reagan soapbox, accuses the powers-that-be of acting like a buffon, who cares? “He’s the president.” Pynchon’s realism becomes a Trumpian mirror: a figure of intellectual dishonesty so ignorantly plastered across our screens that you’re forced to accept fiction as fact.

The novel’s backdrop: post-60s idealism rolled under 80s GDP growth, is a portal to Gen-Z political anxieties. Against Trump’s scrutiny of US aid (and his dislike of less favourable talk-show coverage), US programs masquerade as welfare but operate as propaganda. In the modern ‘third world amusement’ park, American teens hashtag TikTok recordings of ICE kidnappings as #LA Music fest to stop their content becoming shadowbanned. Meanwhile, Israel bombing campaigns over Palestine coincidentally peak on America’s most distractible moments: Superbowl weekends. As of writing this, an ICE facility in Texas was just shot up. The media barrage is both calculated and unending. Rather than teaching or learning the news, we speak in memes and quotes, where our ultimate surveillance state, Palantir, is just a name for Tolkien’s all-seeing orb. Any semblance of America’s hippy-dippy 60s heyday is crushed under a boot. In its wake, every frisson is magnified, every “carefully multiracial” group now offended, pitched against each other in a culture war fueled by bots and algorithms.

PTA’s version of Vineland promises a lot more violence—the highlight reel of the explosions Pynchon prophesied in his novel’s final acts. Paul Thomas Anderson is perhaps the most capable of narrowing the prism Pynchon fitted for us thirty years ago. We are stuck in the past. Charlie Kirk, the baby toothed grifter who went viral for debating students, just had his lungs blown out by a wannabe discord mod; the Gen Z assassin ejecting bullet casings with the words ‘U R GAY’ and the cheat codes for fascist space marine videogame onto a university roof. Never before has Pynchon’s Americana marriage of pop-culture and violence been so absurdly close, never before has politics and media been so acutely meshed into our screens. Our world, at once mysterious and manipulated, is a vacuum that’s easily filled by dimestore conspiracies. Pynchon, safe, untraceable, all buckteeth smiles, was right to keep his head down when he saw what was coming in Vineland. The Tube is incessant. “A lot of people we know,” realises Flash, Brock’s dimwit informant, living in a government witness safehouse “—they ain’t on the computer anymore.”