Art & Photography, Confessions

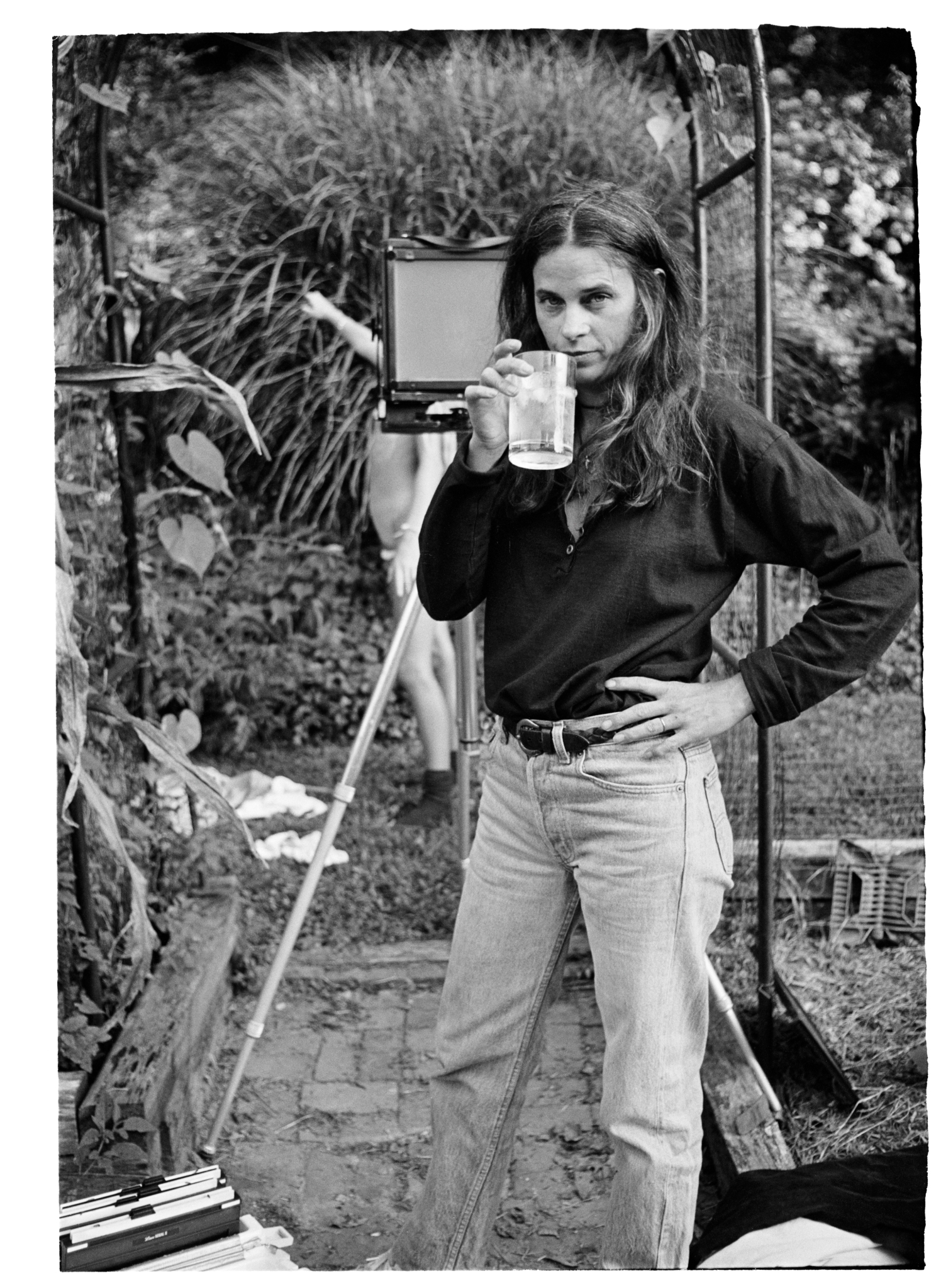

The American photographer—who gained fame and notoriety for her 1992 work Immediate Family—has just released a memoir which reflects on her life and lessons as an artist.

Sally Mann is a fast talker. When I speak to the photographer, Mann bounced from one conversation to another, trying to keep up with the ideas pinging in her head. After a few minutes of conversational entropy, I try to get the interview back on track, but she just laughs. “Oh, forget it,” she said. “No one has a controlled conversation with me. My brain is so nuts.”

In contrast to the rapid pace of her mind, Mann’s work is slow: most of it relies on 8 x 10, large format cameras, meaning long exposure times, long developing times, and long printing times. In recent years, Mann’s images have dealt with the scars of history in her native Virginia. Memories of the Civil War and slavery linger in her haunting landscapes, that—visually speaking—could have been taken in the nineteenth century.

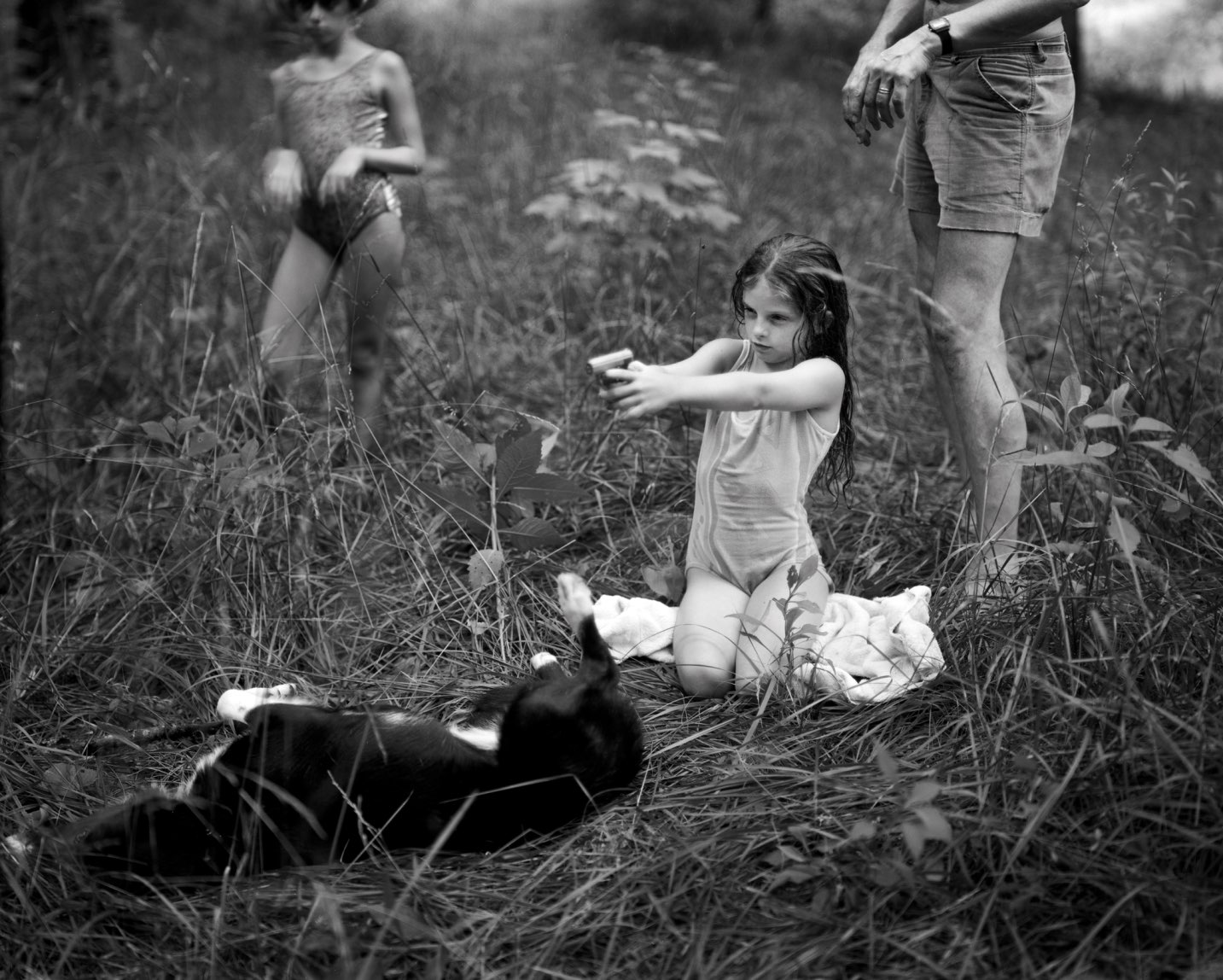

Mann’s work disturbs our notions of innocence. Whether she’s photographing her own children at play or dead bodies at a research facility (as in ‘body farm’), Mann always finds beauty in the horrific and anxiety in the beautiful. Her 1988 collection At Twelve is a portrait series of twelve year old girls, many the daughters of Mann’s friends. The photographs are striking for their troubling beauty—the girls are posed like women, and the juxtaposition between the purity of the girls’ faces and the resolution of their gazes discomforted many viewers. But it wasn’t until Immediate Family that Mann and the discourse around her images came to national attention.

The 1992 book made headlines for its intimate portraits of Mann’s own children—playing, swimming, sleeping—taken at her family’s cabin on the Maury River. In many of the images, the children are nude. Some on the conservative right described Immediate Family as child pornography, and the controversy placed Mann at the heart of the culture wars in America. It’s difficult, therefore, to have a conversation with Mann without asking her questions she’s been asked thousands of times before. Every interviewer wants to talk about Immediate Family. Surely Mann needn’t be defined by these photographs from over thirty years ago.

Yet, the political climate under the second Trump administration has brought censorship issues to the fore of Mann’s work once again. Earlier this year, five of her works on display at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth were seized by Texas police. The case has since been dropped. Now, at 72, she’s written a new book, Art Work: On the Creative Life, which is about the pleasures and pressures of living as an artist. Or, as the book’s very first sentence bluntly states, it’s about “how to get shit done.” Like Hold Still (Mann’s 2015 autobiography), Art Work weaves together photographs and personal memories, but her new book elaborates more fully Mann’s thoughts on being an artist today—confronting self-doubt, creating art whilst raising a family, and remaining politically engaged when working on personal projects. And, of course, the trials of speaking to the press …

HR: Early on in Art Work you write about the “perceived necessity of self-promotion.” Is self-promotion a necessary evil to being an artist?

SM: I say in the book that if you’re good enough, you shouldn’t have to do it. Your work should do all that for you. But it’s not a perfect world. So you have to get out there and do it. And there are so many ways to do it now, which I don’t do. But that’s how young people get their work out there.

HR: I presume you’re talking about social media. Do you think social media is a good thing for artists?

SM: People tell me that they see lots of great work on there. I know people get discovered on social media. They’re on Instagram, and all of a sudden, they’re photographing the cover of Vogue. I guess that’s a good thing. I didn’t have that. It was torture for me. So anything that gets good work out is a good thing.

But the segue there would be, what about the abundance of imagery? Does it hurt discernment in some way? Are you just overwhelmed? Are there just too many pictures? You know, when I started out, I had like five books and I memorised them. There was Edward Weston, there was Ansel Adams, there was Wynn Bullock, there was The Americans [Robert Frank]. There were just very few books out there. So I would look at each picture so carefully and study it and think about it. And now there just isn’t time to study and think about art. You’re just besieged with it. For me, art was precious, and it’s become less precious.

HR: Thinking about that abundance of imagery, I wondered what your thoughts are around generative AI and how people relate to visual images now.

SM: When I was growing up, I believed pictures were real and true. I believed they were not manipulated. My first awakening to the realities of manipulation and mendacity was that famous picture – Yves Klein’s Leap into the Void. There’s a guy bicycling along on the street and a man is diving from a wall, like a swan dive onto the street. It was faked somehow and it’s obviously pre-digital. Jerry Ulsman was doing double exposures and whimsical conflations of imagery long before anybody else. You couldn’t figure out how he did it. And it was so clever and so beautiful. He was the first person to do that. That’s when it became possible, in my mind, for photographs to lie. Up until then, I always thought they told the truth.

HR: So do you think AI is a dangerous thing or do you think it’s good we can do this now?

SM: I suspect that I should say that it’s a dangerous thing. But I look at those pictures and I go my God, these are amazing pictures. And you have to ask yourself, does it matter if it’s great art?

HR: I’m quite surprised to hear you say that. I assumed you would have negative feelings about AI. I suppose one of the arguments against AI imagery is that it’s not really being created by a computer, but rather is just a composite of other people’s work.

SM: My friend John Grisham is part of a lawsuit now with a bunch of other writers who are suing the people who use their work to teach AI. I have a friend in France who sent me a story which listed the photographers that some company is using to teach AI how to make artificial pictures and I was among them. I should be indignant and I should hate it. But sometimes you look at those pictures – and I haven’t seen that many because I’m not on the computer all that much – and sometimes they’re really quite alluring.

HR: So you weren’t angry when you saw yourself among those listed in that article?

SM: You know, what’s the point? You might as well rail against the weather. AI is coming, and it’s going to change humanity in just incomprehensible ways. I don’t have any doubt about that, but I’m old and I’m going to be dead.

HR: I was rereading your first book, Hold Still, and you talk about the ethics of portraiture and how it can be one-sided and invasive and extractive. But in the new book, you say that photographing people can actually be mutually rewarding. How have your views on photography’s relationship to power changed?

SM: It’s changed significantly. I haven’t done that many bodies of work that involved portraiture. There was At Twelve. There’s always a power dynamic, and if the child is twelve, even more so. And then, of course, we have to get into the family pictures [Immediate Family] – which seems inevitable in this conversation – and then the photographs of the Black men that I have worked on for a whole decade. And that raises a whole different set of ethical questions. Avedon nails it. He said that the subject is almost always what he calls an “innocent”, unless they’re in the public eye or they know how to use the camera. They can be taken advantage of so easily by a photographer. So my attitude has changed a lot. I knew I could take advantage of my models in the past. And I’m not sure I want to do that anymore.

HR: How do you feel about the fact that you’ve come into this interview assuming that I’m going to ask questions about Immediate Family?

SM: It would be disingenuous to say that I don’t think that it’s a powerful body of work. It is powerful and very divisive and – the old word, the old hackney word – it is controversial still, maybe even more so now. So I expect it, but I’m not annoyed by it. It’s just that … I’m annoyed by it! (Laughs) I know it’s coming. I know everybody wants to talk about it, but I guess that’s just a testament to the power of the work. So maybe it’s not all bad. I’ve always sort of assumed that history would take care of those pictures for me. But interestingly, the arc of their existence is now tilting towards more censorship, more opprobrium, more risk than ever. And that’s, of course, due to the political climate in the United States.

HR: What’s it like being an artist in America today, when there is this top-down pressure on artists and institutions?

SM: I think it’s really scary. And I think the Fort Worth thing is just the beginning. I think that Project 2025 is going to go into effect and already is well into effect. And art is going to be significantly at risk. Look what’s happening with the Smithsonian. They’re completely whitewashing the entire history of the United States. They know the power of art. The Stephen Millers, the Russell Voughts, they know that art is powerful. And they’re really trying to clamp down on it. And I think we’re going to see a lot more of that.

HR: In the new book, you urge artists to take an activist stance.

SM: I do. And I wish I had enlarged on that, actually.

HR: Do so now?

SM: We have a platform, we have a voice. We have to get our work out there. I think artists really have to stand up. I’ll tell you who’s doing it: Nan Goldin. She’s using her art platform to champion her causes. She’s using her platform as a major artist to speak out, but her pictures aren’t about opioid addiction, her pictures aren’t about the war in Gaza, right? She bifurcates her work and her activism. Let’s talk about artists that actually use their work to change things. And I’m not talking about photojournalism. Bertinski! He’s a perfect example. He’s bringing climate change to the fore, but very beautifully, because a lot of those pictures are gorgeous. So there’s two different ways to do it. I’m sort of in the Nan Goldin camp because I protest, I write letters, I do all that. I’m very active. But it doesn’t come into my work. Yet.

HR: Yet?

SM: Well, I don’t know. I’m pretty fired up about what’s going on. I just don’t know how to approach it, artistically. Beauty! I still like beauty. It’s hard. [Sebastião] Salgado did it. He made the horrific beautiful.

HR: That makes me think of some of your photographs of the Civil War battlefields. Beautiful landscapes, but coated in horror and history. It seems to me that your work has always been political to some degree.

SM: Yeah, it’s addressing those things, but you could look at it and not know. You could look at those battlefield pictures and just see them as nice pictures.

“AI is coming, and it’s going to change humanity in just incomprehensible ways. I don’t have any doubt about that, but I’m old and I’m going to be dead.”

Sally Mann

HR: What are you photographing now?

SM: I’m testing this funky film my friend Evan came across. He gave me a couple of sheets and said, ‘Well, if you can’t think of anything to do, why don’t you take pictures with this film?’ So I just went out and started taking pictures with it. I went to this place called Point Comfort. I heard about it in the New York Times’ 1619 Project, which the Trump administration is trying to squelch. Point Comfort is the place on the James River here in Virginia where the first slave ship docked. That’s where I photographed the James River, this massive, mighty river that carried all the slave traffic, you know, until slavery moved further south.

HR: It sounds like your work – even the landscapes – has a greater meaning today than, say, fifteen years ago.

SM: It does in a certain sense because of the political situation here. I just don’t feel like I can waste my shot. I think I have to take pictures that are saying something. I’m doing two projects now. One is these river pictures. They’re sort of like the battlefield pictures: you can look at them and just see beautiful pictures of flowing water. But if you know the context, that adds a little dimension. But the other thing I’m doing is digital colour. So much fun. So much fun! I am loving it.

HR: I never thought I’d hear Sally Mann say she’s working in colour and digital photography.

SM: I just love it.

HR: It’s great that you’re still reinventing yourself and your style. What’s the lesson there for artists?

SM: Keep trying new things, I guess. I believe you really only have one story to tell, each person has one defining compulsion. It’s the various ways with which you tell that story that makes you a great artist. And I realise I’m still telling the same story. I’m going back to rivers, I’m going back to Mississippi, but it’s so exciting being able to do it in different forms. Colour has just opened up a whole new world for me. It’s so easy too!

HR: You write in the book about the difference between personal and visual memory. Do photographs help us remember?

SM: No, they don’t. Because I think they undercut memory, and override it, and produce new memories, often incorrect memories. I think that’s been scientifically proven now. Now my fundamental memories of childhood are from photographs, little family snapshots. It’s dangerous. But think of the vivid memories that you young people are going to have because you have so many pictures of yourselves. You don’t have to bother to remember.

HR: Isn’t that a bad thing? For young people who are taking photographs every day on their phones.

SM: I don’t think it’s good or bad. I just think it’s a phenomenon that exists and there’s nothing you can do about it. It’s been there ever since photography was invented.