In one of three essays exploring the allure of islands in cinema, we consider how Rossellini used the volcanic backdrop of Stromboli to tell an elemental story of love that extended off the screen.

Stromboli Island. There are idyllic islands, and then there is Stromboli. Off of the north coast of Sicily, an overbearing shadow is cast on a small islet; the symbol of ruin and death: Mount Stromboli—one of the active volcanoes of Italy, and the home of Aeolus, master of the winds. Here, two souls were brought together to tell a story about finding a home in the presence of foreboding, eruptive nature.

Roberto Rossellini’s neorealist classic Stromboli (1950), starring the filmmaker’s lover, the legendary Ingrid Bergman, is about a displaced Lithuanian who secures freedom from an internment camp during the second World War by marrying an Italian camp guard. But as soon as she catches sight of her new home, she is aware she might have made a mistake: “This is a ghost island!” she proclaims, “Nobody lives here.” Mount Stromboli keeps a guardful eye, like a panopticon, over the inhabitants, many of whom do not take kindly to the stranger and do their utmost to make her feel unwelcome and trapped. Karin—who comes from the European social class that have long realised Italy through its most graceful cities and islands—begins to see herself in another prison camp; isolated between the narrow staircases and square houses, surrounded by the water and backwards locals that are in the process of coming and going (many of them to America). But Stromboli is difficult to get away from. The volcanic fumes are intoxicating.

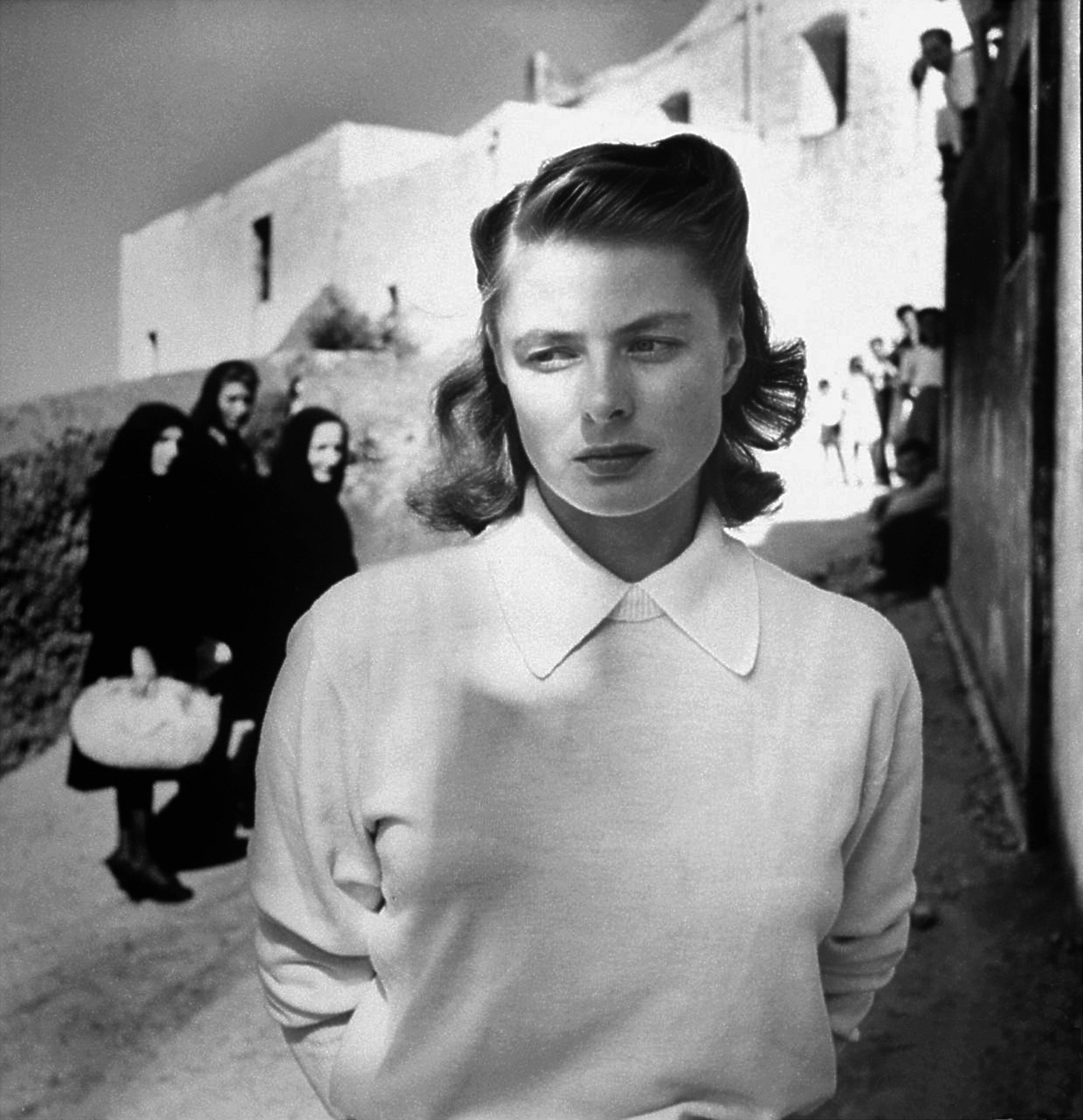

Ingrid Bergman in Stromboli, Italy, 1949. By Gordon Parks for Life Magazine.

Perhaps Stromboli reflected the state of both Bergman and Rossellini at that moment in their lives: both trapped in unhappy marriages with other people.

Perhaps Stromboli reflected the state of both Bergman and Rossellini at that moment in their lives: both trapped in unhappy marriages with other people. It would begin an extramarital affair that caused great scandal in Europe, as their child being born out of wedlock before the film’s US release (the original plan was to have Anna Magnani, Rosselini’s erstwhile lover star in the role—but perhaps the themes may not have come across the same way). When the news of the affair was broken, Bergman would be denounced as a ‘powerful influence for evil’ by an American senator—and her career was halted until her Oscar-winning performance in Anastasia.

But throughout their collaborations, notably with Stromboli, Europe 51 and Journey to Italy, the filmmaker exposed the anguished version of the actress that was probably truer to her than the glamorous roles she became famous for. On that island, Rossellini saw Ingrid Bergman—her emotions and profoundly complex character. Perhaps in hindsight, this is why the setting of Stromboli takes on such a deep meaning; and why it remains among Bergman’s most touching performances. Throughout our lives we find ourselves lost, imprisoned, and uncertain of whether there is an escape. The active volcano, the fumes of death, the judgement of those around us—who do not try to know us—inspire an action. Like Karin, Bergman acted as a bold, modern woman, who sought self-determination; her oft-quoted introduction letter to Rossellini setting the scene for what would become her own liberation as a woman and as an artist. On that island, for all its desolation, both the filmmaker and the actress found freedom in one-another—and Stromboli, the film, would inspire a freedom in the next generation of Italian filmmakers to bravely confront alienation, fear, death, and religion. A new ‘realism’ was found among the ashes of that desolate island.

Read next: Islands on screen: Sicily in Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura (1960)

Read next: Islands on screen: Capri in Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris (1963)