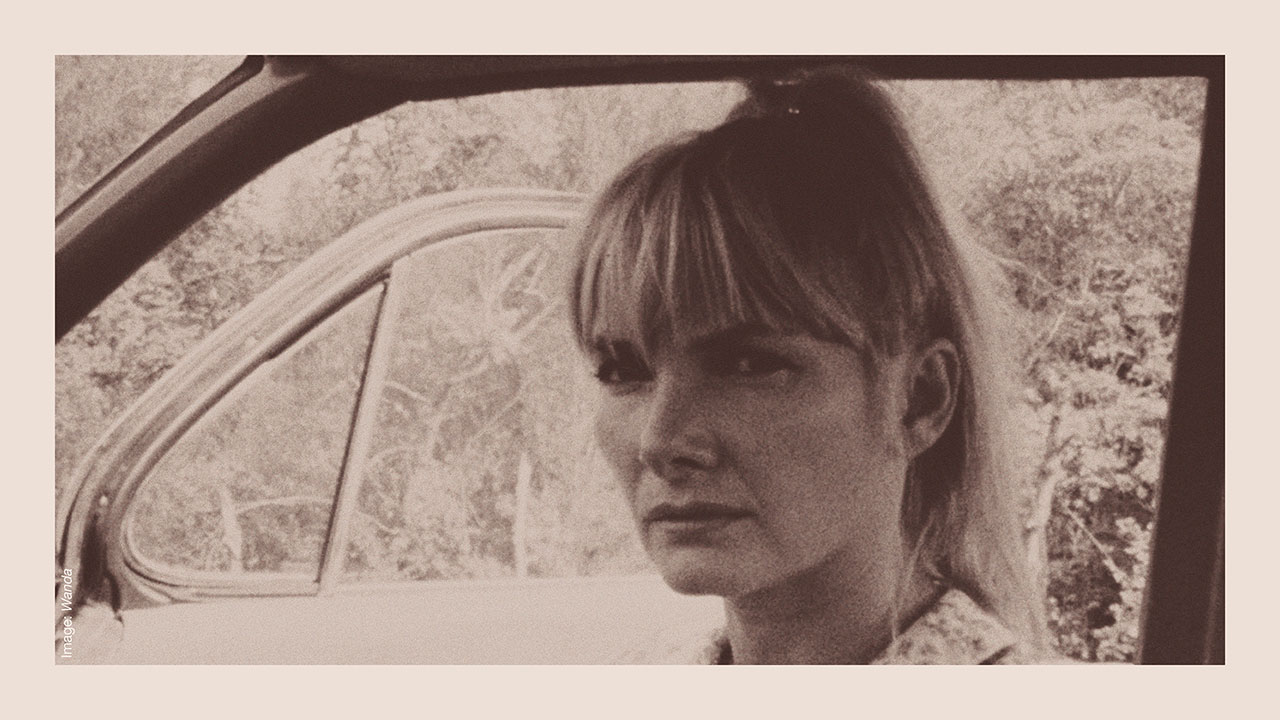

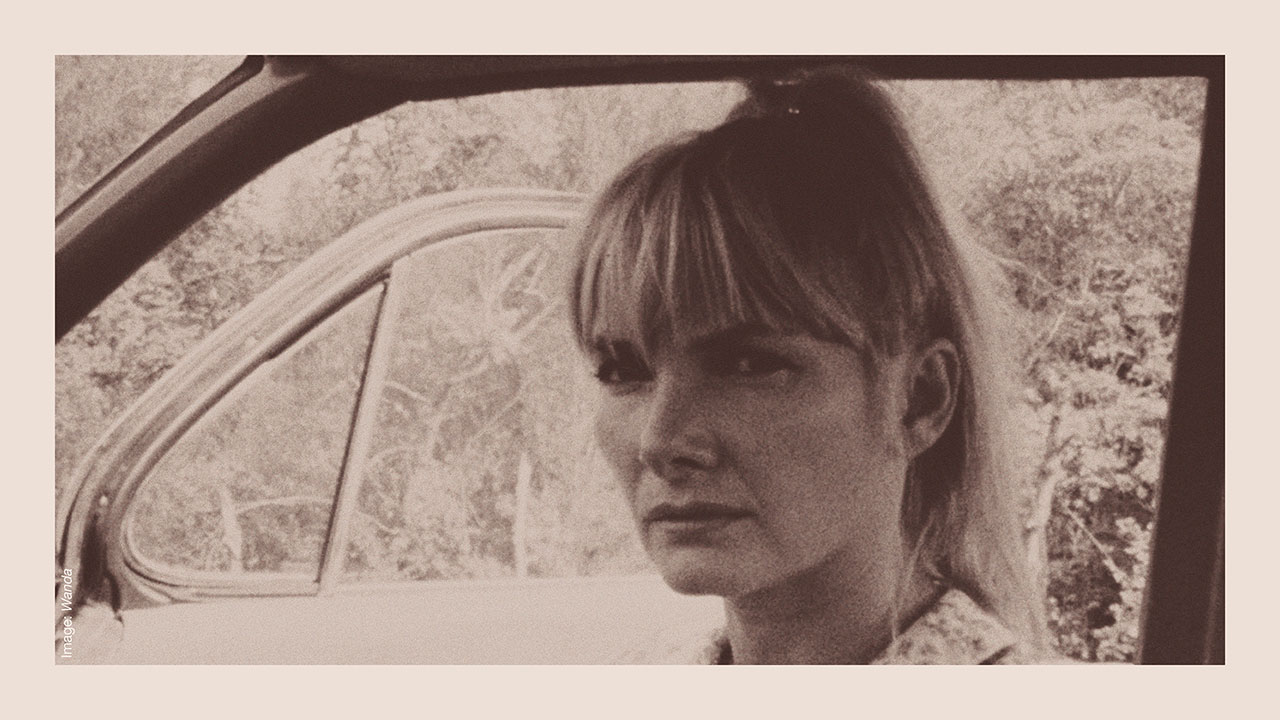

As recent retrospectives and restored editions of works by artists such as Barbara Loden, Mai Zetterling and Chantal Akerman prove, we are living in a moment that celebrates once underexamined women artists are getting full recognition, but it was willful neglect, misogyny and aversion to experimentation that allowed them to ever disappear.

In recent years, much has been made of ‘rediscovered’ female directors. Many have been given the full retrospective treatment in cinemas across the UK (Stephanie Rothman and Barbara Loden), while others (Julie Dash and Jennie Livingston) have had their work restored and reintroduced to new audiences through the likes of MUBI, BFI Player, and so on. There’s no doubt that censorship, limited distribution, and critical neglect have left countless women’s films overlooked, dismissed in their time only to be celebrated decades later. But as with rediscovered art of any kind, this begs the question: what can we do to stop the work of female directors today from being buried, lost, or forgotten?

The fate of Shirley Clarke’s documentary Portrait of Jason (1967) offers an important lesson here. Upon its release, the film was largely ignored or dismissed upon its release. Its unvarnished depiction of a Black gay man proved too niche for mainstream moviegoers; the titular Jason, too loquacious to sustain a viewer’s attention for an entire film of just him talking to the camera. Though Portrait of Jason is now hailed as a landmark of queer cinema—and by Ingmar Bergman as “the most extraordinary film” that he had ever seen—after its unprofitable run in New York cinemas, the film’s original print was assumed to be lost until it surfaced in the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research archives in 2013. An intensive restoration effort for the original print received over $26,000 on Kickstarter, along with funding from the Academy Film Archive, the Winterfilm Collective, TIFF Cinematheque, and, rather wonderfully, the actor Steve Buscemi.

Kathleen Collins, a civil rights activist and one of the first Black women to direct a feature film in the USA, was also no stranger to the challenges faced by female filmmakers. Her debut feature-length film, Losing Ground (1982)—which charts how a philosophy professor’s summer unravels as her husband becomes increasingly consumed by his art and other women—never played outside of the film festival circuit during her lifetime and wasn’t picked up for distribution at the time. The exact reasons remain unclear. When the film was restored and reissued by Collins’ daughter in 2015, it was met with rave reviews. Five years later, the Library of Congress selected Losing Ground for preservation in the National Film Registry, citing its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance.

Stephanie Rothman, image courtesy the Barbican.

These cases might suggest that it’s surprisingly easy for films to go missing. But these aren’t cases of lost genius so much as wilful neglect—their films buried not by time but by an industry that has only recently found it fashionable to care. Rediscovering female creatives of any kind also risks relegating their work to the hazy category of women’s art where gender, above all else, can factor into how something is marketed and, in turn, critically received. I was grateful that Isabel Stevens, curator of the recent Chantal Akerman season at the BFI, notes that the auteur refused to class herself as a feminist filmmaker simply because she was a woman. Her queerness, Jewish heritage, and gender were integral to her artistic practice, but these qualities didn’t define or overshadow the work itself.

“Avant-garde cinema” is a strange, formal category. By Sight and Sound’s measure, Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) is the greatest film of all time: its power comes not from radical abstraction but from an almost excruciating fidelity to the everyday. Where so many films smooth over the passage of hours, Akerman forces you to inhabit them, to feel their slow, cumulative pressure—the kind of cinema that relies upon, as per the mantra of second-wave feminists, a spectatorship that could consciously bridge the personal and political. The writer and director Marguerite Duras—who had a full retrospective at London’s ICA last summer—demanded the same of her audience; an “incurable” Communist in her own words, she scorned mainstream cinema which she believed could well be used as state propaganda. Instead, she believed that her films weren’t “made for people who love cinema. I didn’t think about those people for a second.” It’s only in recent years that Akerman and Duras’s films have been realised as the cinematic landmarks they are—celebrated, ironically, for the very experimentalism that once alienated mass viewership.

Chantal Akerman. Image courtesy BFI and Collections CINEMATEK Fondation Chantal Akerman. © 1976 Babette Mangolte

If the form and contents of their films deterred audiences of the time, the conditions in which female directors have often worked pose a challenge of their own. In focus at this year’s International Film Festival Rotterdam, the German director Katja Raganelli created a series of documentary portraits of female filmmakers between the 1970s and 80s, including the likes of Delphine Seyrig—the titular Jeanne Dielman and star of several Duras films—Varda and Valie Export. But Raganelli was less interested in creating glossy portraits of her peers than she was in exposing the material and cultural realities of cinematic production for women. On the set of La Musica (1966), Seyrig recounts how Duras was forced to work with a male coordinator on the film. (In 1981, Seyrig’s very own Be Pretty or Shut Up! would also compile various testimonies from other actresses, including Jane Fonda, and Shirley MacLaine, talking about their experiences of misogyny, discrimination, and abuse on set.) As IFFR programmer Olaf Möller notes, Raganelli’s work risked being lost forever; in her native Germany, her films “were rarely reviewed, and barely ever seen again after their original airing.”

Raganelli often self-financed her projects, some of which would remain incomplete because of this. Which is no surprise, of course; since the dawn of cinema, men have dominated production, distribution, and financing in commercial film. Things have gotten slightly better for female filmmakers, but only just. Watching Andrea Arnold’s sublime, Palme d’Or-selected Bird (2024) earlier this year reminded me of the director’s triumphs despite her background. Walking the fine line between cautious optimism and pathos, the film is set in Arnold’s native Kent: pebbled beaches, marshlands, and a council estate, not that unlike the one she grew up in. But opportunities for working-class women are few and far between, and Arnold’s later-in-life success (at 43, her directorial debut Wasp won the 2004 Oscar for Best Live Action Short Film) says volumes about this.

Yet there is also, still, the matter of censoring films made by women. While Amanda Nell Eu’s Tiger Stripes was nominated as one of the Academy’s picks for Best International Feature Film this year, the director disowned the film after Malaysian cinemas censored a scene showing period blood on a sanitary towel. (“What hurt was the things they cut out were the heart of the film,” Eu said. “It was censoring the beauty of a young girl, her freedom.”) And as Haaniyah Angus points out in her brilliant essay for A Rabbit’s Foot lamenting the lack of Black female directors, limited screenings and online archives of their work – as well as their general exclusion from undergraduate film curricula—have inevitably created a blindspot when it comes to their contributions to film. “I wonder if it’s simply just racism or if it’s disinterest,” she writes. “Honestly, I can’t tell which is worse, and does one exist without the other?”

These should all be cautionary tales of the kind of talent we risk losing in real time if the industry doesn’t change. But it’s simply not enough to demand better representation: we actively need to push for systemic shifts in funding, distribution, and more equitable working conditions for the next generation of female filmmakers. That way, we might not have to wait decades for their work to be seen, let alone celebrated.