Whilst the 1960s are an under-examined period of the British artist’s oeuvre, a new exhibition explores how David Hockney’s rebellious spirit always demanded our attention.

On a spring afternoon in St James’s, Mayfair, I arrive at Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert to see In the Mood for Love: Hockney in London, 1960 -1963. Tucked in between antiquarian booksellers and auction houses, the gallery sits in a pocket of London where history feels both intact and inhabited. Curated by Louis Kasmin, the exhibition assembles a rare and intimate collection of David Hockney’s early works, many unseen since they were first created in the early 1960s.

Hockney arrived in London from Bradford to study at the Royal College of Art in October of 1959, aged 22. The works in this exhibition span those formative years, paintings, drawings and etchings that capture Hockney before he was Hockney. Even then, he was unmistakably himself: wry, self-aware and bold. The works on view reflect his playful defiance, with graffiti-like inscriptions, “QUEEN” , “LOVE” and “THRUST”, offering a window into his emotions and desires. “When you contextualise them, they are quite remarkable,” Louis tells me. “Not only are the images very bold and in your face, the titles are deeply suggestive.” These early works emerged in Britain where homosexuality was still illegal. It would be a further seven years before being gay was decriminalised, yet here is Hockney in 1960 painting with startling confidence, writing “QUEEN” across the canvas and turning the vertical structures into metaphors of lust and desire. It was an act of both artistic and political defiance. As Louis puts it: “they are so loaded, and it’s funny that people haven’t really looked at [Hockney’s early works] properly, because he puts more into these than he does into so many of his later works. ”

For all their radical content, these works also reveal a young artist of remarkable discipline. “Even though he was experimenting a lot,” Louis says, “he had such a drive and direction that a lot of people don’t have… for someone in his early twenties, this is such a cohesive body of work.” Many of these works have not been publicly shown since the ‘60s or ‘70s. In one case, Louis tells me of a serendipitous and “deeply fortuitous” visit to a collector’s house. A study long thought lost, its existence known only through a Polaroid in Marco Livingstone’s archive, reappeared when Louis stumbled across it by chance, whilst getting a glass of water in a collector’s kitchen. “It was a stroke of luck,” he says. There’s a sense of serendipity here, of the works finding their way home.

David Hockney, “Two Friends (in a Cul-de-sac)”, 1963. Oil on canvas. 42 x 48”. © David Hockney

Louis Kasmin’s role in this narrative runs deep. His grandfather, the legendary dealer John Kasmin, was one of Hockney’s earliest and most important champions. He began representing Hockney in 1962, when the artist was just 25, and continued to do so for over three decades. Their collaboration helped define post-war British art history and brought Hockney’s work to an international audience. Louis notes, “Kas was dealing with a young chap who was three years younger than him… and their relationship was such a strong one. I think it’s wonderful.”

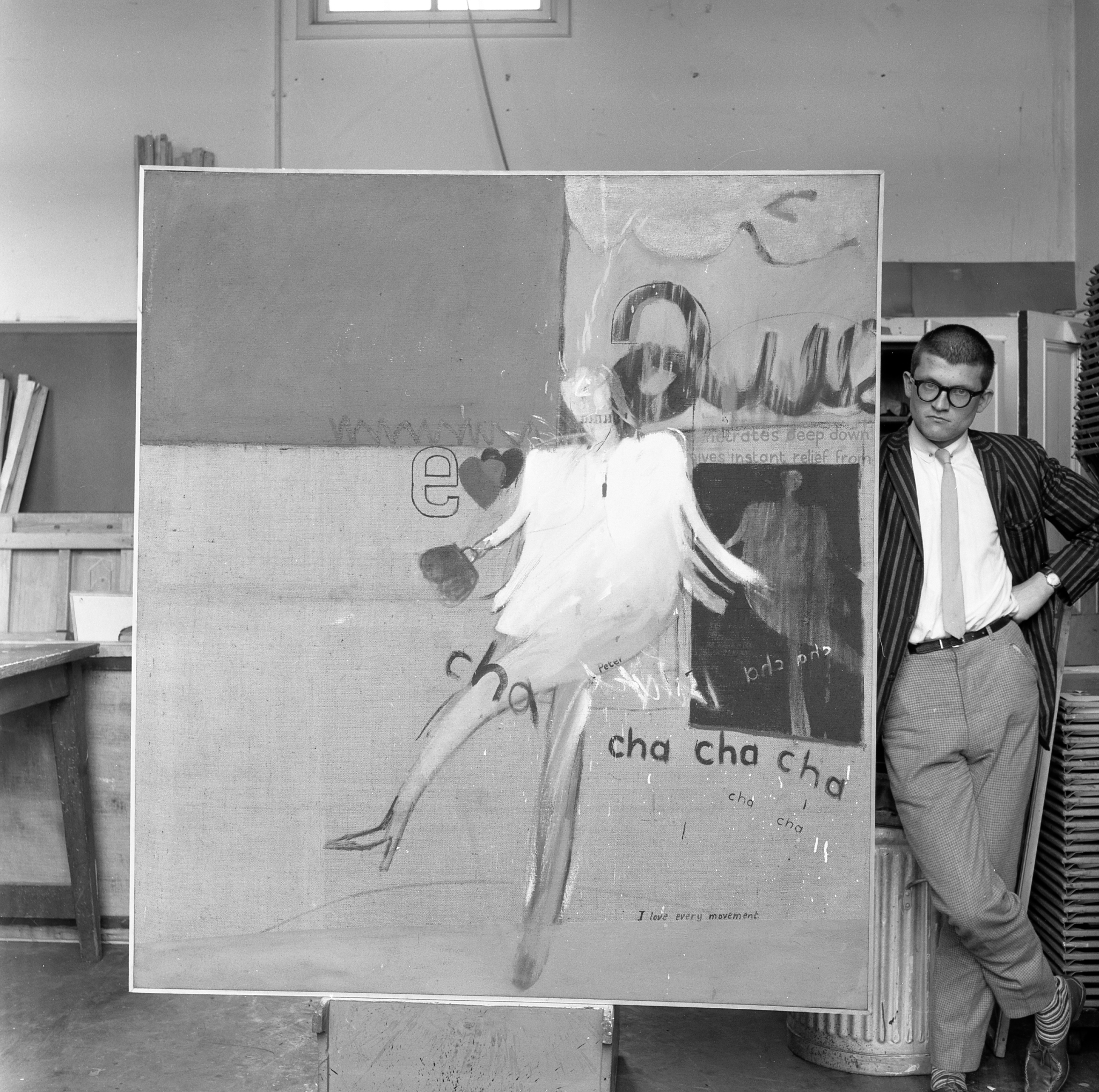

The exhibition’s second act gives ways to figuration. One work, The Cha Cha that was Danced in the Early Hours of 24th March 1961 depicts Hockney’s first romantic crush, Peter Crutch. Though not a long-term partner, Crutch became an object of fascination and longing in Hockney’s early 1960s works. Here he appears mid-movement, a moment that feels half memory, half performance. The painting isn’t so much a portrait as it is a feeling. Here, Crutch became a stand-in for the kind of crush that’s all nerves and no outlet—the rush of wanting someone out of reach. Hockney paints him with warmth and a flicker of mischief.

In Life Painting for Myself (1962), Hockney broke classroom conventions by choosing to paint his friend Mo McDermott rather than the prescribed female model in his life drawing classes. McDermott would go on to become a frequent and significant sitter. Intimacy was always Hockney’s subject, even when disguised in theatricality. Louis directs my attention to the corner of one canvas, scrawled graffiti from a fellow RCA student reads: “Don’t give up yet.” Hockney left it in.

“In July of 1960… the Tate staged Britain’s first major Picasso retrospective. The exhibition was revelatory for Hockney and his contemporaries. Here was Picasso in full force, a shape-shifter, rule-breaker, and a master of reinvention.”

Image: David Hockney, “I'm in the Mood for Love”, 1961. Oil on canvas. 50 x 40”. © Royal College of Art. Royal College of Art, London

Then there’s The Salesman (1963) which may, or may not, be a portrait of John Kasmin. “I’ve just had an argument with Kas about as to whether that is or isn’t him,” Louis laughs. “Kas is very literal and says he would never wear a hat like that, even though I see him every time in a hat like that.”

John Kasmin, Hockney’s first dealer, has remained a close confidant for over three decades. His presence anchors the exhibition, physically, in the paintings and spiritually, in the stories behind them. “My relationship to the art world is entirely different to his,” Louis reflects. “Whereas he was dealing with a young chap who was three years younger than him… I mostly deal with artists who are dead.”

It is this generational dialogue, between Louis and Kasthat gives the show its pulse.. The energy of those early years is still alive, not least in the retelling of the legendary “Tuesday Nights.” These raucous gatherings, hosted by Kasmin and his circle, gave artists, dealers and collectors a place to drink, dance, and collide. “Kas in the ’60s was a different animal,” Louis tells me. “I’ve only ever known him as teetotal and a postcard collector with a phenomenal memory… but back then, I’m sure lots of them were sleeping with each other—in a safe and enjoyable way. It was that sort of world.” We both laugh. “Tuesday nights sound like heaven,” I say. He agrees.

To understand Hockney’s evolution during these years is also to understand the changing tide of the 1960s. In 1960, just as Hockney was completing his first year at the Royal College of Art, the Tate staged Britain’s first major Picasso retrospective.The exhibition was revelatory for Hockney and his contemporaries. Here was Picasso in full force, a shape-shifter, rule-breaker, and a master of reinvention. For Hockney, still shaping his own artistic voice, it opened a door. One could be many things at once: personal and political, sincere and subversive, even romantic without sentimentality.

While Picasso’s impact was undeniable, Louis reflects on the wider cultural constellation that shaped Hockney’s early sensibility. Among the most enduring presences were poets such as Walt Whitman and Constantine Cavafy. Both wrote openly about love and desire between men; Whitman with expansiveness, Cavafy with introspection. Hockney read them both. And though their words are never illustrated outright, their presence lingers in the tenderness of his compositions, in the way intimacy is made visible without spectacle.

David Hockney, “Composition (Thrust)”, 1960. Mixed media on board. 46 1/2 x 35”. © Royal College of Art. Royal College of Art, London

That same spirit carried him across the Atlantic. In 1961, Hockney travelled to New York for the first time, funding the trip with earnings from A Rake’s Progress. It was his twenty-fourth birthday. He arrived wide-eyed, unpolished, and instantly taken by the speed and scale of the city. The energy of New York, the artists, the streets, the men, would leave its mark. If London had formed him, New York gave him permission. Louis reflects on the moment’s significance: “Previously, everyone had looked to France and Europe, but suddenly America was this exciting new place.” Abstract Expressionism was in full swing, and the centre of gravity was shifting. For Hockney, this new world presented something altogether different

But what makes the show sing is its emotional core. For all its references to poetry, painting and politics, In the Mood for Love is, at heart, about becoming. About the thrill of seeing and being seen, of claiming a space in the world through art. It captures a young man discovering his voice and daring to use it.

There is a tenderness in seeing an artist on the brink. Not yet canonised, but already carving a language of his own. These works pulse with confidence, risk and the ache of becoming. In the Mood for Love doesn’t just show Hockney as he was. It offers a glimpse of the man he was becoming. Not yet the darling of Hollywood or the subject of retrospectives, but a twenty-something in London, drawing his way into clarity. A man about to make a bigger splash.

In the Mood for Love: Hockney in London, 1960–1963 is on view until 18 July 2025 at Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert, 38 Bury Street, St James’s, London SW1Y 6BB.