The Taiwanese auteur’s seminal work uses photographs and one-sided conversations to reveal unexpected insights into his characters’ subconscious.

Camera, coma, comma; these are all words which put things on pause: light, consciousness, a sentence. In English, they even fit into each other like Russian nesting dolls, half-rhyming, half-not. A camera and a coma both feature heavily in Taiwanese auteur Edward Yang’s three-hour millennium masterpiece, Yi Yi (2000), which follows the middle-class Jian family around Taipei after their matriarch, Ruyun Tang, suffers a stroke. The family brings Ruyan home to their apartment, and takes turns having one-sided conversations with her. In her comatose state, they confess things they might never have if they truly believed she could hear them. Meanwhile her grandson, eight-year-old Yang-Yang, becomes obsessed with taking photographs of the back of people’s necks, because they’re the only part of our body we can never see with our own eyes.

In Yi Yi, Yang interrogates his characters’ desires as they put their lives on pause for Ruyan: Yang-Yang’s sister Ting-Ting experiences her first love, his mother Min-Min disappears on a silent retreat, and, unbeknownst to anyone, his father NJ gets back in touch with his ex-girlfriend. Yang-Yang’s dream of showing people a side of themselves they cannot see is ultimately not too far from the self-revelatory potential with which Yang imbues Ruyun’s coma. In each case, time must be paused for perspectives to shift, and life to eventually shift along with it.

In Mandarin, the film’s title, Yi Yi, meaning literally “one one,” is written as two lines: 一一. Written vertically, it resembles the character for the number two: 二. The repetitive nature of the film’s Chinese title, lost in English as And A One and A Two…, itself evokes a sense of pause. The characters themselves look almost punctuative, though they indicate a break in more than just a sentence. In keeping with Yang’s predilection for symmetry, the film is bookended, like a Shakespearean tragedy, by a wedding and a funeral. And yet, in Yi Yi, these events take on more than just a conventional role; they are the precedents of definite change around which the rest of the film, and its directionless protagonists, revolve.

In keeping with Yang’s predilection for symmetry, Yi Yi is bookended, like a Shakespearean tragedy, by a wedding and a funeral.

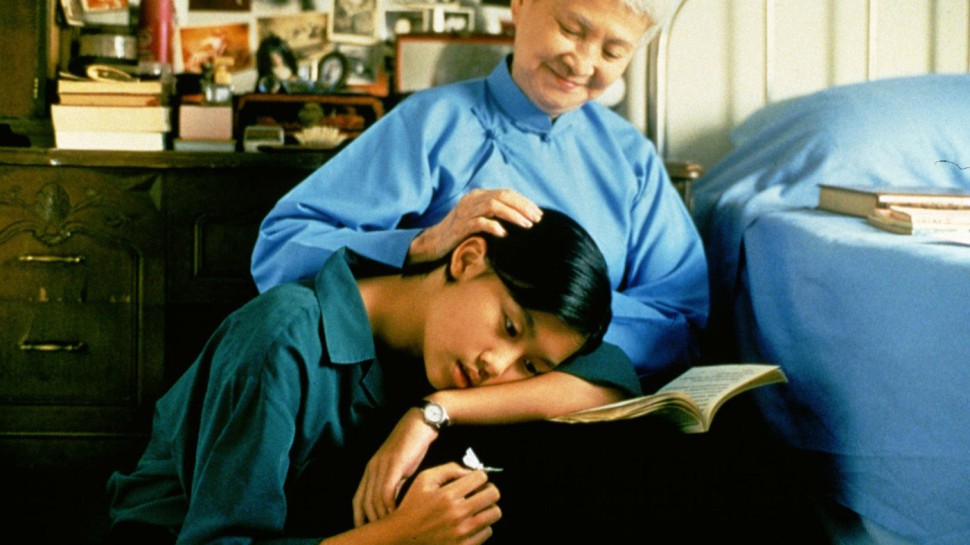

A still from Edward Yang’s Yi Yi (2000).

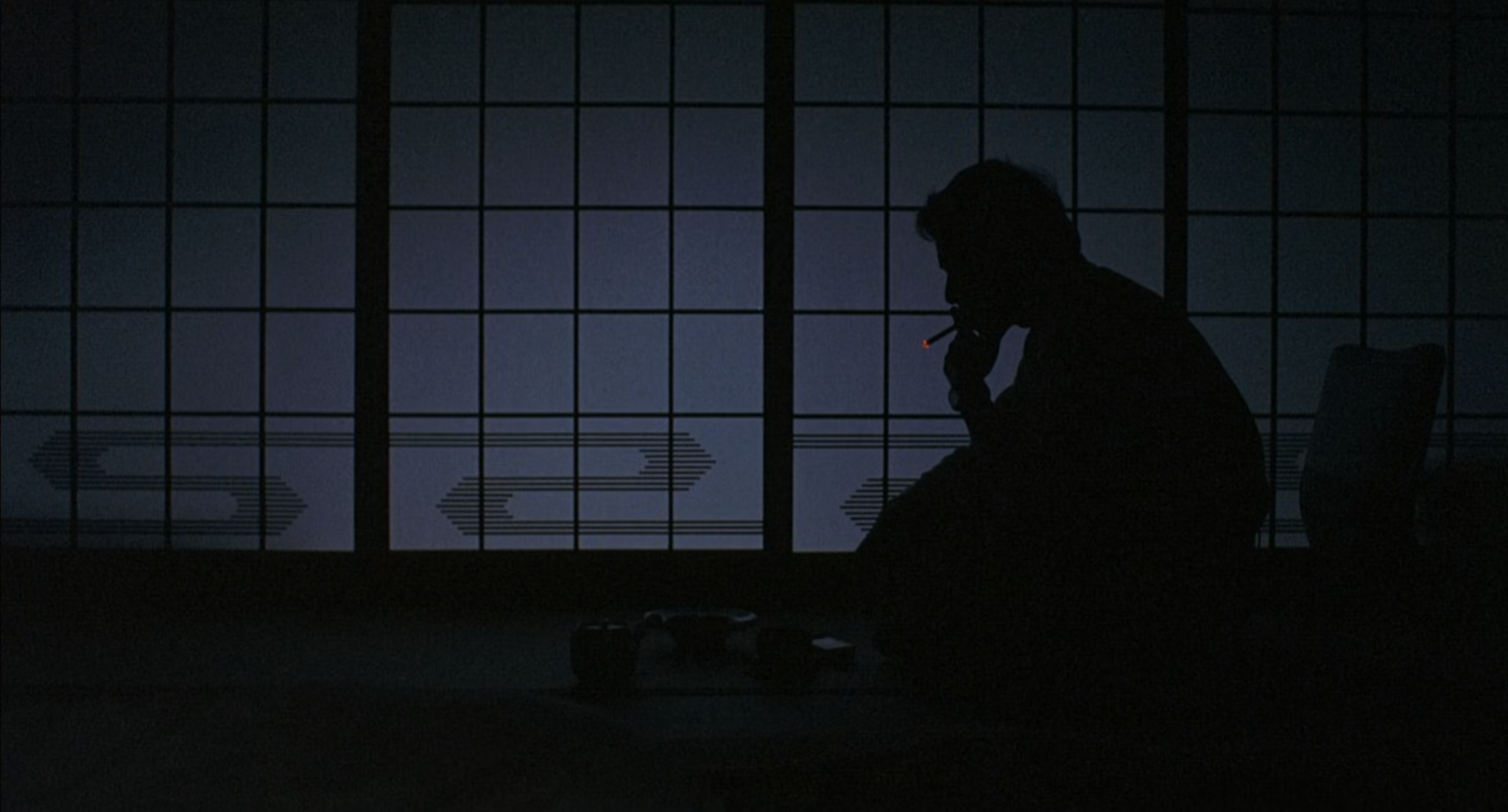

Of course, Yang’s sense of aesthetic specificity stretches far beyond the visual idiosyncrasy of Yi Yi’s title. Like his previous epic, the five-hour teenage gangster movie A Brighter Summer Day (1991), Yang’s framing allows for the messiness of real life not only to seep in at the edges, but to occasionally take pride of place. The Jian apartment is cluttered, sometimes dirty, yet always present. He shoots almost exclusively in long shots, framing characters with door frames, mirrors, or car windows. In this way, Yang allows his characters to truly inhabit their environments, rendering their moments of contemplation and turmoil all the more meaningful.

Not long after Ruyan’s stroke, Min-Min sits Yang-Yang on her lap next in his grandmother’s bedroom, and explains, “From now on, we’ll take turns to talk to grandma. It will make her wake up sooner.” Yang-Yang is confused and a little scared by the medical equipment surrounding his grandmother’s bed. “There’s lots to tell her,” Min-Min says, encouraging him, “Like what happened at school… Or some little secret you have.” All the while, she is gently poking Yang-Yang’s chest, right next to his heart. The moment foreshadows subsequent confessions, in which the liminal space of the coma allows the Jian family’s thoughts to wander.

Ultimately these thoughts drive Min-Min away, to take time to reconnect with herself. Sometime after she has left, NJ sits down next to Ruyan’s bed. “Seems I’m the only one left to keep you company,” he says, sheepishly. But after a few fumbled attempts at conversation, the situation unlocks something in NJ: “It’s hard for me to mumble like this. I hope you won’t be offended if I say… It’s like praying. I’m not sure if the other party can hear me, and I’m not sure if I’m sincere enough.” His feelings flow in a tentative, yet steady stream. “Frankly, there’s very little I’m sure about these days,” he says.

The adults’ lack of clarity in Yi Yi is counterpointed by Ting-Ting’s earnest romance, and Yang-Yang’s precocious behaviour. Seeing Yang-Yang buying rolls of film from the local camera shop always reminds me of the Japanese TV Series Old Enough, in which a camera crew follow small children sent on errands by their parents to see if they’re “old enough” to do them. It is only later that we see NJ discover Yang-Yang’s photos in his bedroom one day. He stands sifting through the photos – person after person shot from behind. Yang doesn’t allow us NJ’s reaction – it’s enough that we see Yang-Yang’s photos have had their desired effect, even if it wasn’t quite how he intended.

In both Yi Yi and Fanny and Alexander, the purpose of these scenes is not to impart intergenerational wisdom, but rather to place the young and the old in space together, where they can share an acceptance of the world’s mystery – even its evasiveness.

The film culminates in an ambiguous scene between the other of Yang’s youngest characters, Ting-Ting, and Ruyan, who appears briefly to have magically awoken from her coma. Ruyan is sitting next to her bed making origami when Ting-Ting comes in. Ting-Ting admires the white butterfly her grandmother has made, before kneeling down and resting her head on Ruyan’s knee. She asks, “Grandma, why is the world so different from what we thought it was?” She pauses for a moment, before asking, “Now that you’re awake and see it again, has it changed at all?” We never hear Ruyan’s response, and when Yang cuts back to Ting-Ting waking up from a nap, it seems the whole thing might have been a dream.

The scene recalls another at the end of Ingmar Bergman’s theatrical cut of Fanny and Alexander (1982), in which Alexander, a boy of around Yang-Yang’s age, lays his head on his own grandmother’s lap, and listens to her read from Strindberg: “Everything can happen. Everything is possible and probable. Time and space do not exist. On a flimsy framework of reality, the imagination spins, weaving new patterns.” In both Yi Yi and Fanny and Alexander, the purpose of these scenes is not to impart intergenerational wisdom, but rather to place the young and the old in space together, where they can share an acceptance of the world’s mystery – even its evasiveness.

On a date with Ting-Ting, her boyfriend tells her,“My uncle says, ‘We live three times as long since man invented movies.’ It means movies give us twice what we get from daily life.” Yi Yi glows with this sentiment, fortified by Yang’s delicate touch. It feels reductive to trace symmetries, themes, and motifs in a film like Yi Yi, which is so clearly about more than that – perhaps the exact opposite. While it’s satisfying to unpack the aesthetic patterns of Yang’s epic, its message might be closer to that of Fanny and Alexander: “Everything can happen. Everything is possible and probable.”

The BFI’s The Films of Edward Yang: Conversations with a Friend season continues until 18th March.