Director Audrey Diwan discusses her contemporary remake of Emmanuelle, an erotic roman à clef by Emmanuelle Arsan which achieved notoriety and commercial success as Just Jaeckin’s 1973 porno-inflected film adaptation. Set in the vacuumed world of a luxury Hong Kong hotel, Diwan has taken the archetype of French culture in an entirely new direction.

At the beginning, I wasn’t interested. My producers handed me the book of Emmanuelle six months after Happening came out. I was curious to read it, but not for a project. It’s a story of a woman told by a woman, and it felt different to what I saw in the 1974 movie where she’s an object. Two thirds of the way in, there is a very long conversation between Emmanuelle and an older guy. It’s a philosophical conversation about eroticism. I started wondering how we can explore eroticism in our society. Can it work nowadays? It all started from that question. Is there still a place for imagination in eroticism, because of what pornography has done to our society? Pornography shows everything, there is no room left for the audience’s imagination, whereas eroticism works collaboratively with the audience. I like the collaborative aspect of eroticism. I present the story and then you imagine the rest.

My Emmanuelle has nothing in common with the original plot, just the broad idea. I wanted to use her as a vessel, because Emmanuelle is an archetype in our society. The story does start in a plane, and I did that intentionally, thinking, “I’m going to propose another journey and see where it heads.” But then I felt completely free to keep absolutely nothing. There will be people who hate it because they are still attached to the old version, but I’m ready for that.

Audrey Diwan and Noémie Merlant in Paris by Fatima Khan

For the opening scene, I spent a long time in the editing room. I felt like I was missing something. Are we in the gaze of the man? And step by step, the eye and the point of view reverse. I wanted to look at her, but also to be her. She’s trying to get him to follow her. I added the sounds, because you can hear the breath, and suddenly, even if we are not sharing her gaze, we feel it’s her point of view. The idea was to say: that’s the old way of looking at Emmanuelle, and then you have the reverse. That’s the other journey.

Turning Emmanuelle into the story of a woman who doesn’t feel pleasure—that was a challenge. There were people who were strongly against this idea. I was helped by very good producers, who wanted this new Emmanuelle to exist, but it wasn’t easy. I couldn’t have just made a film about a woman’s sexual journey who wasn’t Emmanuelle. Maybe it’s dangerous but I wanted to play with the name because it meant something to reverse some ideas, to fight against representation.

I had three main ideas that gave me the desire to make the movie. How do we work and use the frame? Then, the relationship between the characters. An eroticism which comes from how we look at each other, what we learn about each other. The idea of relationality was central. Can we connect and get out of our loneliness? Then, finally, the idea of beauty. Can we depict this story in a very beautiful way? Can aestheticism, which is uncommon in pornography, be a part of the story of Emmanuelle?

An erotic story isn’t about bodies. It’s everything that is in the atmosphere. A storm can be erotic in a way. The way you play with sound, elements, the metaphorical part of it. And I realised words can be erotic, of course. I realised I didn’t want eroticism to be the moment where people are naked. Eroticism is in what you hide and what you show, but also in waiting to see someone again. When you’re in Hong Kong, everyone talks about In the Mood for Love (2000). Everyone remembers it for being an erotic movie, which is interesting because nothing happens between them. They just pass against each other, meet each other in corridors, exchange a few words. Eroticism is not a question of the body.

I wanted to find a way to talk about pleasure in general. Emmanuelle’s job is quality control, to make sure the client’s wellbeing is the best it can be. She makes notes: good, bad, green, red. It’s an organised, artificial definition of pleasure that our society upholds. The idea of performance is everywhere. The performance of a woman, being the best version of yourself every day. With the set design, there are mirrors everywhere. We are here to perform, we have clients. I think it’s the same for sexual relationships. You climax, you have pleasure. It’s a common idea in our society. You succeed in life by completing a performance.

I included a reference to Wuthering Heights in the film because British culture is important to the movie. I picked Hong Kong as a setting because of its colonial history and what we still feel of the presence of England. Naomi Watts is the head of the hotel, where the action takes place in English. And then you go lower in the hotel, and there you find the local people. We are in a post-colonial time, but those hierarchies still exist. And, with the luxury world and how it is organised, you especially still feel those ideas in our society today.

Pornography shows everything, there is no room left for the audience’s imagination, whereas eroticism works collaboratively with the audience. I like the collaborative aspect of eroticism. I present the story and then you imagine the rest.

Audrey Diwan

Happening and Emmanuelle tell two different sides of our sexual life and what society imposes on us. Annie Ernaux’s character is not escaping from her sexual life, she’s escaping from the consequences. And it’s political. You feel society has decided for her. It’s the same thing here, because you have standards, you have to pretend. It’s an escape game. I don’t know when I’m going to stop writing about it. I’ve started working on adapting another book, The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell. It’s about the youngest duchess of Florence, Lucrezia de Medici and how she got married in order to produce an heir, and the same ideas—of what society imposes on women—are very strong in it. It’s like a trilogy. I’m attracted to that kind of story, but I always make sure my characters fight against it.

Let’s see what is erotic. I love words. I come from literature and I wanted to explore what the words can do for us. And it’s funny, because when you see that sex scene in the plane, it’s quite cold. And I don’t feel anything. I feel like her—not in my body and unsettled. And then when you explore it with words and someone you connect with, then I hope the feeling is different. But we’re talking about the exact same thing. But it’s the way you convene your own sensations and the way you want to share. Sharing is everything. It makes it erotic. She tells him intentionally and opens the door. Opening the door, even with words, is bringing the other into your fantasy.

We created different voices for the characters. With Noémie, we worked with a gesture coach to find different bodies. She has one body which is very cold and vertical, and it comes with one voice and step by step, with another body she opens up. She doesn’t behave the same way. Her shoulders are down and she sits differently. Her voice changes, too. This conversation in the hotel restaurant, they stay quite neutral. We managed to make it the turning point of the movie. It’s like music, we keep searching until one day we can trust that we have the music. It was interesting rehearsing that scene with Will and Noémie. Seeing how they could create that atmosphere. It’s a still shot for seven and a half minutes. So it’s about how you can keep the audience’s attention.

The most important work was before the shooting—to create a space where everybody felt comfortable. So we talked a lot, and rehearsed, but not choreography, more like a philosophy. What do we want to do? What are we trying to build and reach together? I decided we’d have a lot of time to create those sequences because we need to be able to take time. Does everyone on the set feel comfortable? Are we all in the right place? It was complicated to portray the feminine climax—we had to think about it a lot, to go against the old school representation of women shouting to make the men happy that pornography has created throughout the years. We’ve seen so many films where it’s badly depicted. When you get the chance to correct it, you have to be very precise. It’s fake but it has to sound true. It’s subtle work, but Noémie is a great actress.

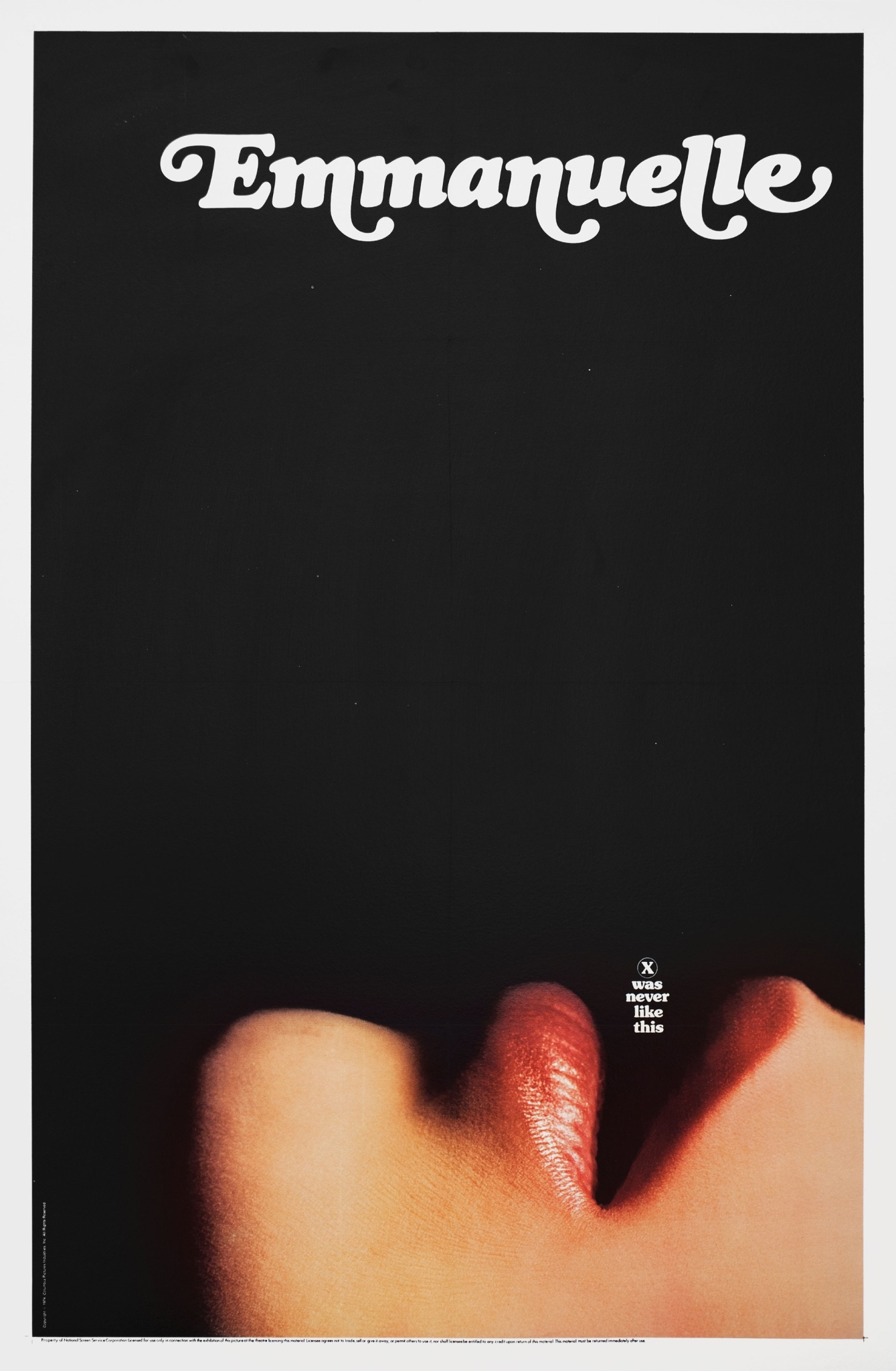

Poster for Emmanuelle (1974). By Just Jaeckin. Courtesy of Posteritati.

An erotic story isn’t about bodies. It’s everything that is in the atmosphere. A storm can be erotic in a way. The way you play with sound, elements, the metaphorical part of it. And I realised words can be erotic, of course.

Audrey Diwan

We all lived in the hotel before the shoot. We were able to rehearse on set, which is something that never happens. We got familiar with the atmosphere of the hotel, and we would rarely leave. It was weird. The whole crew was there. We shot for five weeks, and I arrived three weeks before. We spent two months in this magnificent, strange place. We were in the same state of mind as the characters.

Emmanuelle has all this time to experience the hotel, but also realise how lonely you can be in those places. You are surrounded by people but you are lonely at the same time. I really wanted to work on that feeling. What is it to cross people’s paths and exchange a few words and never get deeper. Even sex is surface. With the DOP, Laurent Tangy, we intentionally worked on something that is slightly not real. It’s a world in itself. The sounds are not regular sounds. That makes me want to breathe, open the door and try something else. I wanted the characters to look for something else. To get rid of their standards and habits.

Cléo de 5 à 7 (1962). By Agnès Varda.

I had Agnès Varda in my mind, especially Cléo de 5 à 7 (1962). It’s about how much we can trust in the ability of a character to have a revolution in such a short period of time. For Cléo it is one day. And it’s a very special day because she’s wondering whether she will live or die. She’s very self-centred and not very connected to the world. And in the middle of the movie there is a switch. And Varda plays with the camera: you start watching the world instead of looking at Cléo in mirrors. I love that movie, because I believe that revelation. I can actually believe that this young singer becomes something much deeper.

I also thought of Steve McQueen’s Shame (2011). The topic of the movie is how people can run out of desire. And how they can reconquest that desire. I rewatched Jean Eustache’s La maman et la putain (1973)—the way they talk freely about sex inspired me. It was new for me when I first watched it—these gigantic discussions where everything can be said. It was a revelation. Can we be that earnest in conversation?

Noémie Merlant in Emmanuelle (2024). By Audrey Diwan. Courtesy of Pathé.

Kei doesn’t exist. He’s a ghost. Emmanuelle invents him in order to go back to herself. So he’s a mirror. He tells her things that are true about her. She doesn’t know where she lives anymore. Her values are defined by the hotel she works for. Everything he tells her about himself is also true for her. My casting director introduced me to Will Sharpe. He is sensitive with strong and modern ideas about gender. We had a very strong connection. He watched Happening on New Year’s Eve alone while watching the kids. Because he’s an actor-director, we could share ideas about the frame.

I think two things can happen. If you share the feeling with Noémie on the plane and then you travel with her, or you stay out of the bathroom and you’re going to struggle with the movie. It’s an experience, where you either jump in or you stay out. So people who expect the old Emmanuelle will probably stay out, but I feel a strong connection with the other kind of people who actually get in the story. It’s a physical experience in a different way. I don’t intend to convince everybody, but I know the movie can find its own audience.

Emmanuelle will be in UK cinemas from 17 January 2025 and available digitally from 24 January 2025.

Photography by Fatima Khan

Creative Direction and photography by Fatima Khan

Production by Anna Pierce

Videography by Luke Georgiades

Audrey Diwan is wearing Chanel

Noémie Merlant is wearing Louis Vuitton

Make-up by Aurelie Deltour

Hair by Miwa Moroki

Read also: “She goes into her belly. She goes into her flesh”: Noémie Merlant on becoming Emmanuelle