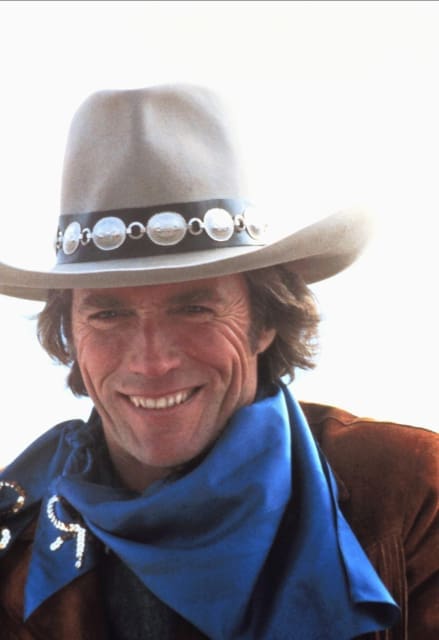

The first time I saw Clint Eastwood was on the screen at the drive in theater in the San Fernando Valley, where my dad took my siblings and me to see a triple feature of the Spaghetti Westerns. I was around ten years old and the only other examples of iconic stars I had seen were James Bond and The Beatles. I watched A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, and nothing in my young life would ever be the same. This was my first experience with the Wild West and what the American Spirit stood for.

Around 1986, after several years as a musician, concert promoter, record company executive, personal manager and budding movie producer, I was hired as a Vice President of Production at Warner Bros. On one of my first days at the company, I ran into marketing executive Joe Hyams, who knew my mom from their days working in NYC. Joe—who was to become a major force in my life—invited me to go with him to visit Clint on the recording stage, where he was putting the finishing touches on the music for his film Bird. Joe said since I was from the music world I should meet Clint, and he wanted Clint to know some younger executives at the company. When we entered the studio, many of the original musicians from Charlie Parker’s band were playing their parts, and there was Clint, conducting the session. Clint was recreating the life of one of our greatest musicians in one of the most creative periods in our cultural history.

During a break, Joe introduced me to Clint, and we talked for a few minutes about the film and our mutual love of jazz. I guess Clint thought I was okay, because soon after Joe called to say he was taking Clint to the US Film Festival in Utah (now Sundance) and invited me to join.

One morning before the festival got underway, Clint and I decided to hit the slopes and were loading onto the chairlift when a young woman popped in between us as we left the station. About halfway up the hill, our guest was in the middle of sharing her artistic aspirations with Clint. Suddenly she dropped one of her ski poles, only for it to reappear in Clint’s hand. “Fastest gun in the west,” he explained coolly.

Bill Gerber: Clint, it amazes me that you were already 28 when you got your real first break doing Rawhide. You had a wife and two kids and really needed a job. Then along comes Sergio Leone and you’re shooting Westerns in Europe. You become an American icon, representing what John Wayne had previously been for decades in terms of American grit. Did you want to follow in the Duke’s footsteps?

Clint Eastwood: I did like John Wayne very much, but I also really liked Gary Cooper and Jimmy Stewart. They made some amazing films. They did the kind of pictures I was doing later. A lot of people put me in that category. I was astonished.

BG: Had you worked with horses before you started acting?

CE: Yes, when I was in the army I did get to ride horses a little bit—that kept me sane.

BG: I remember you telling me once that you even suggested to Sergio that he should get some close-ups because he was only doing wide shots.

CE: It’s true. I said: “Sergio, I come from television, and you’re going to need some coverage to cut this together.” He did get very tight on the closeups, and it became a signature look.

BG: I recently re-watched The Outlaw Josey Wales. Did growing up in the wake of the Great Depression affect your narratives in film?

CE: You know, we were very poor when I was young, and we had to move around a lot. My mom was incredible. We had people coming to our door all the time looking for food or work, and my mom would try to give them a potato or something, even though we had so little.

BG: It was a pleasure to meet your mom. She felt right out of a Steinbeck novel, and you were a devoted son.

CE: When we were at the Academy Awards in `92 for Unforgiven I got the award for directing; I was so petrified that I forgot to thank my mom, who meant everything to me. I went backstage and then to my seat, and I was beside myself. I was determined to tell her how I felt about her and decided that even if we didn’t win Best Picture I was going back up there to make it right. Luckily we won and I was up there giving her the thanks she deserved.

BG: Pale Rider was a game changer. I think that was when the world recognized you as a director to take seriously, and it all seemed to happen at the Cannes Film Festival. Do you remember much about how it went down?

CE: Yes. It wasn’t in competition, but we wanted to just put it up for people to see. Our expectations were low. It got a really good running and then I thought: “See, wrong again.” For some reason nobody wanted to do that picture.

BG: I looked it up and the movie grossed ten times its budget.

CE: You know, sometimes it’s just a guessing game. There’s no way to know how it’s going to go. You give it a try. Sometimes you think it’s really going to go, and it doesn’t, and then sometimes it goes great. Sometimes your instincts are good, and your outside intelligence isn’t.

BG: That’s the thing about Unforgiven. One of the miraculous things is that, apart from Dances with Wolves, there hadn’t been an important western in a long time. And coincidentally, Costner loved your film so much he signed on to A Perfect World immediately. I remember sitting in your office with Bob Daly and Terry Semel and you telling us you were finally ready to do the Western; they took about a second before saying, “Go for it.” The truth is we were secretly hoping you were going to do another Dirty Harry film, but you listened to your heart and made a classic.

CE: In my mind it was a good project. I don’t think I could have done anything better than that.

BG: You had had the script for a while.

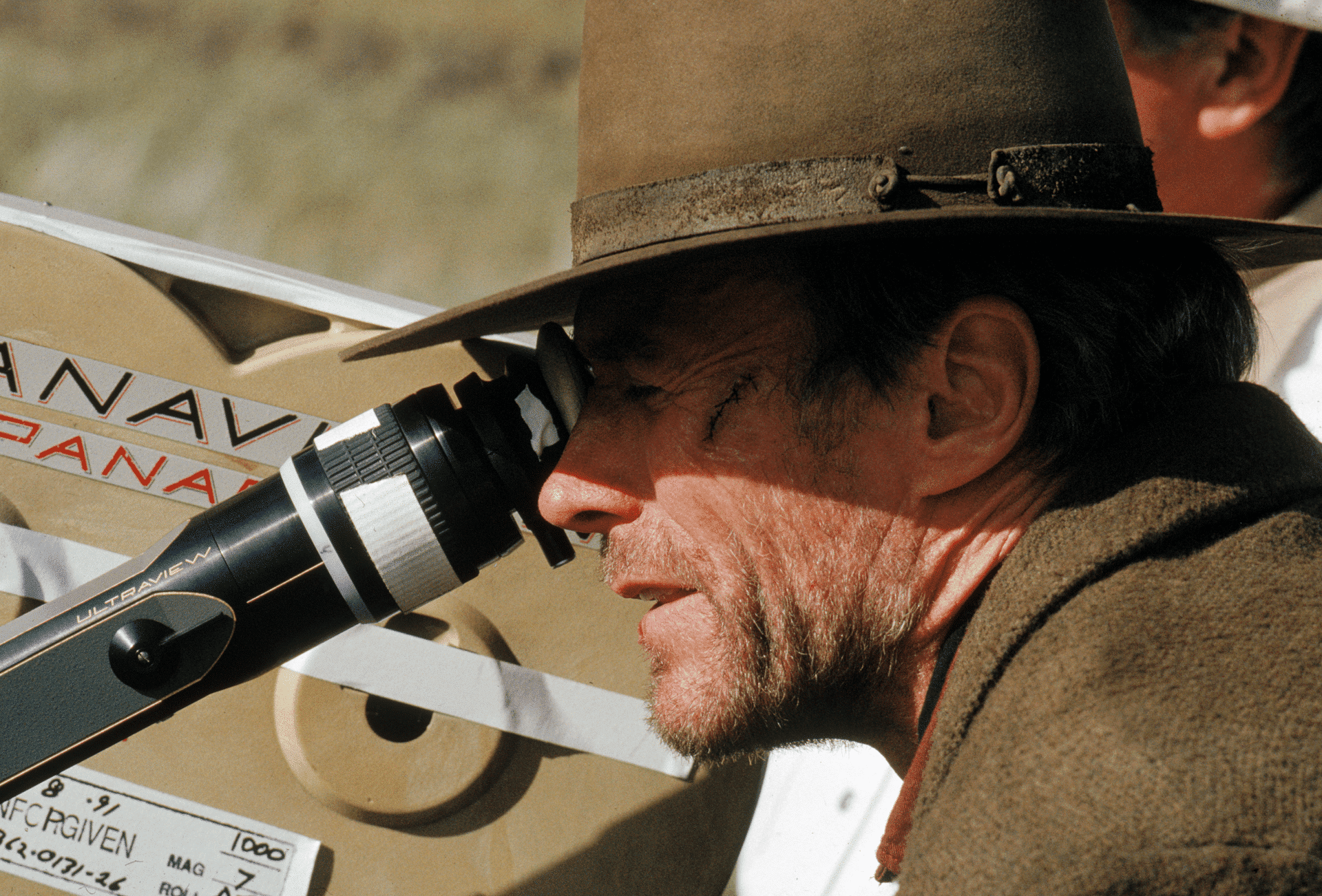

CE: Warner Bros. were developing Unforgiven with Zoetrope up in San Francisco. Then all of a sudden they fell out and Semel said why don’t I do it. I said I couldn’t do it right away and he said just keep it and do it whenever you’re ready. Then I did a bunch of movies in between and finally one day I just said I have to go back to that movie. I took it out of the drawer and put it into motion.

BG: Before you started shooting you had asked David Peoples to try out a couple of your ideas. I remember you telling me that after you read the revised pages you called David and said to not listen to you and to not change a word of the script.

CE: As I recall, that is probably true.

BG: Looking back, you were strongly advised not to make some of your movies, and in the end you made the right choices…

CE: It’s funny, my lawyer and agent hated Every Which Way But Loose. I went ahead and did it. They hated it all the way to the end. Then [publicist Marco] Barla took it down to Texas and put it in front of an audience and everyone went crazy.

BG: It was such a huge hit. And a huge soundtrack album. Speaking of movies you were discouraged from doing—how about Gran Torino?

CE: That was also funny because my agent turned it down. The longer I’m in the business the more I wonder how anybody thinks they know anything. We were all kind of guessing and sometimes you make lucky guesses. You can make a judgment and like an idea, but the public decides. If they don’t think it’s interesting, then it’s tough shit.

BG: Gran Torino was the fastest turnaround of any movie I’ve ever worked on. You read it on Christmas 2007 and it was in theaters Christmas 2008.

CE: When I finished reading it I said: let’s start this tomorrow.

BG: You’ve become a bit of a superhero to people. I was visiting the set of a movie we were making with David Wolper called Murder in the First. We were shooting on Alcatraz and on the ferry ride back to the city I heard a guy telling his buddy that the only person that had survived the swim from the island to the shore was Clint Eastwood. I guess he really bought Escape from Alcatraz.

CE: I think he was dreaming. Incidentally, Frank Sinatra loved the movie and sent me a note about that one.

BG: I was on your set one time and, unbeknownst to the actors, you rolled [started recording] on a rehearsal, and when the actors asked you if you were happy you said you were and there was no need to do it again, you were moving on.

CE: Well I just wanted to get the scene before they started acting.

BG: After Million Dollar Baby, I called you to tell you how I loved the movie. I couldn’t help saying how incredible it was that you were in your 70s and still making important films. You’re a giant who remains relevant and timeless, and yet you said, “Byblos (a nickname I will cherish forever), I continue to work because there are so many interesting stories to tell.”

CE: We’re just about to finish one now. Can’t wait to show it to you.

At 93, Clint Eastwood is in post-production on his 42nd directorial feature, Juror #2. In his own words: “I continue to work because there are so many interesting stories to tell.”

You can purchase our issue 7, featuring cover star Clint Eastwood, here.