The filmmaker goes by Knox. “The name Karen has become persona non grata over the last few years.” She laughs, over a Sunday afternoon call. “It was one of those things where I was too far down my career path to change my name entirely…so I thought I’d try just Knox out, and I’ve stuck with that ever since. The only people who call me Karen now are my family.”

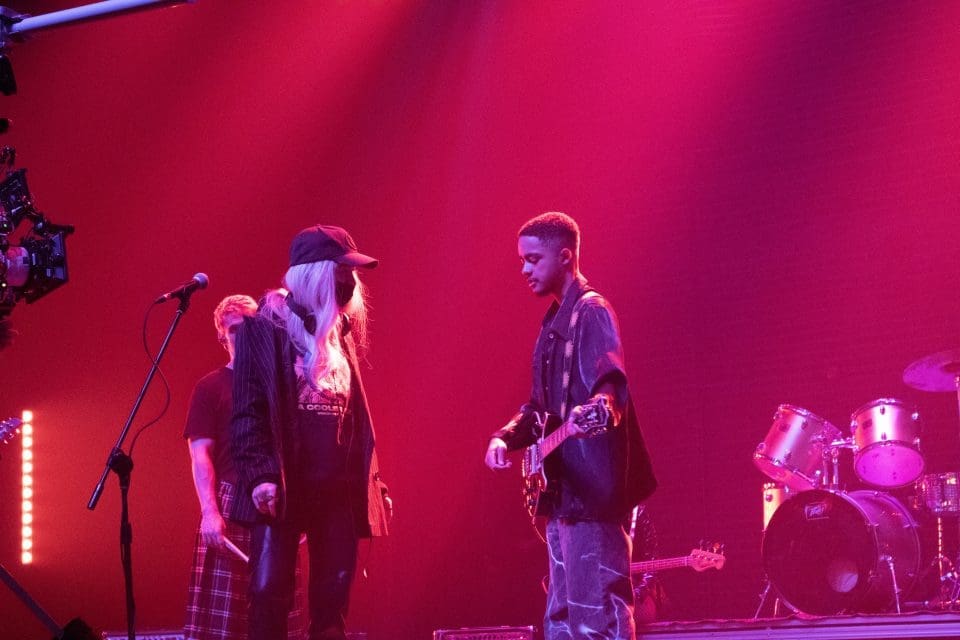

The Canadian director and actor is in London for a few days to premiere her Sophomore feature film We Forgot To Break Up at the latest edition of the BFI Flare Film Festival. An adaptation of novelist Kayt Burgess’ Heidegger Stairwell, the film, set at the dawn of the new millennium, charts the rise and fall of a fictional local punk band named The New Normals after they move from their small Canadian town and chase their big break in Canada’s music capital, Toronto. Their newfound success is threatened when trans frontman Evan (a star-making performance by Lane Webber) gets caught in a love triangle with two of his bandmates.

Knox proudly describes We Forgot To Break Up as “2000s nostalgia-core”—a love letter to the indie punk rock scene in Toronto at the dawn of the new millennium. For her, the movie lives and dies by staying true to the music scene she remembers during her formative years in Toronto. Although she arrived in the big city in 2008—a little late to the party, she admits—Knox can still riff off Toronto punk rockers like she knows each one personally, a surefire way to know if lived and breathed a subculture. “I worked in a Jewish bar the whole time that I was in University. It was an indie/rock live music venue, and I saw a lot of the Toronto music scene come through there.” Some, she actually does know personally—and I’d advise any eagle-eyed Toronto natives familiar with the era to look out for a familiar name as they watch the film’s credits roll. “Stars was such a huge band for me as a teen, I had Set Yourself on Fire on a loop,” Knox says. “I loved them so much that I got Torquill Campbell, the frontman of the band, to actually write all the original music for this film. I knew he was the only person who could do it.”

It’s Knox’s dedication to the spirit of the scene and her adamance that every detail rings true to the time that make We Forgot To Break Up a more considered music biopic than most actual music biopics. Below, Knox talks the “rainbow-ification” of queer culture, why the best biopics are fictional, and how the music and queer scenes in Toronto entwine.

Luke Georgiades: What was the first thing that struck you when you read the screenplay for the film?

Knox: I was super excited by the fact that it was set in the late 90s and early 2000s because I had been watching a lot of band documentaries, like Dig! about The Brian Jonestown massacre. It’s so rich and full of interesting cinematic visual language, and I wanted to bring that to the script. We needed to be able to nail that cinematic language that for me was so present in Dig! and Oasis: Supersonic, which illuminates the chemistry between the band. You watch those and you can tell that these people have been smelling each other’s farts in vans for months and months at a time. We needed that realistic dynamic between our five actors, who are meant to be bandmates who had grown up in a small town together.

LG: This is billed as a love-letter to the music scene in Toronto. Can you tell me a little bit about your own formative experiences with that scene?

K: I worked in a Jewish bar the whole time that I was in University. It was an indie rock live music venue, and I saw a lot of the Toronto music scene come through there. I was listening to Peaches and Stars when I was a teenager growing up in this small town just outside of Toronto. Stars was such a huge band for me as a teen, I had Set Yourself on Fire on a loop. I loved them so much that I got Torquill Campbell, the frontman of the band, to actually write all the original music for this film. I knew he was the only person who could do it.

Me and my music supervisor eventually came to two conclusions: all the tracks had to be of the time period, and they had to be Canadian. I’m so glad we did that. There was a point where I was writing letters to Jack White begging him to let us use this cover of Seven Nation Army. I wrote him a college thesis about why he should let us use that song. But at the end of the day, this movie is Canadian, and it’s so intrinsically about the music scene there, why wouldn’t we have a tracklist that stays completely true to that concept? In film you have to experiment so much in terms of what’s correct for the piece, and usually the answer to the question is the answer that you would have given right away at the start of the project. But we had to experiment with different eras, different sounds, before realising that the answer was in front of us all along.

LG: Can you tell me a bit more about the songwriting process?

K: It was free-flowing, artistic, and imaginative. Torquil lives on the East Coast, and me on the West, so we would just jump on the phone and talk about our dreams. He’d be like “Yo Knox, so what did you dream about last night??” and we would chat about it. It was all very intangible, it was emotional, it wasn’t practical speak. He would go away and write something and come back, and I would give him notes. Sometimes I needed a track to be more anthemic, or dirtier, or more tortured and romantic. And he was a great collaborator in that sense. The first draft he sent in of Revolutionary Heart is almost exactly how you hear it in the film—Brendan Canning from Broken Social Scene said it’s the best star song that he’s heard in twelve years. It’s a banger.

LG: How did you find the right voices for the type of sounds that were being written for the movie?

K: There was no way I was going to cast someone who wasn’t trans for the role of Evan. I needed someone who’s trans, who’s an amazing singer, has rockstar presence, and is also a fantastic actor. Ok, let’s see! [laughs]. I had worked with Lane Webber on a previous project—he had done more comedy than dramatic acting, but I knew the kid had it in him to take on the role. I’m so grateful for him. The first phone call we had about the project I was like “hey, man, do you wanna be the lead in a movie?” and he was like “hmm…I don’t know if I even want to be an actor…” and I was like “sick.” It was the best answer I could have hoped for as a director. This wasn’t an actor who wanted to people-please, and he considered the role in a way that most actors wouldn’t. He wasn’t doing it because he wanted to be a lead in a movie, or to be a star, or to walk red carpets, he was approaching it from an artist’s place every step of the way. If a line didn’t sit right with him he would ask to change it, and I’d say “fuck yeah, let’s change it.” The movie wouldn’t be the same had we not cast him.

LG: How does the Toronto music scene of the time and the queer experience come together for you?

K: Lane is a huge part of the queer music scene in Toronto in general. We often talk about selling out, and I think a contemporary version of that is a sort of rainbow-ification of queer culture. You have these companies trying to use Pride month to get someone to sign up to a bank account or buy their hot dogs. I think it’s important that we champion queer culture, but it’s just as important to retain the iconoclastic, punk identity that is what makes queer art, film and music so radical in the first place. That’s the tightrope you have to walk: how much can you sell out without rendering your art empty of its original iconoclasm. How much is Evan willing to sacrifice to become this artist he knows he’s destined to be? We also used a lot of queer Toronto bands and artists on the soundtrack, like Peaches or Gentleman Reg, a Toronto trans musician who now goes by the name Regina Gently. We wanted to include a lot of the queer music from Toronto in the piece itself. To me, the indie music scene in Toronto and the queer scene have so much overlap because there’s a mutual impulse towards counterculture.

LG: Watching the movie I got the sense that you were really able to unshackle yourself from the traditional pitfalls of the music biopic. You weren’t tied down to reality or the pressure to stick to a certain continuity or reference easter eggs.

K: It’s really surprising to me that we haven’t done this more often in filmmaking. When the Weird Al Yankovic movie starring Daniel Radcliffe came out and was completely fictional, I thought “how the fuck have we not been doing this for years?” It was so cool. I would way rather watch a totally fictional biopic about Freddie Mercury than some state-sanctioned, totally sanitised version of his story. My big complaint about Bohemian Rhapsody was that Freddie Mercury was a hedonist who loved to fuck [laughs] and that was not present in the movie. Where was the fucking? I was bummed about that, because I love Freddie Mercury. Show me the fictionalised biographies, because that’s an opportunity for the artist to then say “what is my interpretation of the essence of this human being?” It smacks our collective hard-on for revisionist history like Hamilton or Bridgerton where we look at historical events and say, you know what would be more fun? If we did it like this. If I want the facts about someone’s life, I’ll read their Wikipedia page, but if I want to understand the essence of an artist, I would much rather watch the artistic interpretation of somebody who knows a shit ton about that artist and has an opinion on them, and wants to reflect back in a story what that artist means to them.

In this film, I felt completely free to mess around. It was freeing to be able to make my own lore around these characters and this band. I love to do that, too, with actors. I love to talk about relationships. How do you feel about this person? What was your relationship like with your third grade teacher? What does this person do for fun? I find people endlessly fascinating. People are my favourite thing, and my only hobby other than film. So getting to create my own universe alongside these people and fleshing out the historical lore of The New Normals was really satisfying.

LG: There’s so much nostalgia built into this movie. Can you tell me about why that was important for you to communicate here?

K: It’s only recently that the 2000s has become nostalgia-core, that we can now look back and make a “period-piece” about that era. We’re seeing a lot of those kinds of movies now, especially in Canada. We had Blackberry, which was at Berlinale, and I Like Movies, which is mostly set in a Blockbuster Video, and now We Forgot To Break Up. A critic in Canada called it “early-2000s Canadian nostalgia-core” and I am in for that genre. A lot of millennial filmmakers are coming of age now where they have the resources and capacity to make movies about their pasts. And while this isn’t directly my past, there are so many elements in it that were deeply nostalgic for me. All of the actors in the movie are Gen-z, so they couldn’t really even comprehend the notion of not having a cell phone, to have to listen to music on tape. I had to walk them through that. And their responses were all like “wow, this must have been so amazing!” And I replied with “yeah, it was, but also, now is great too.”

LG: It’s come to a point where many people don’t really see music or movies as art anymore. It’s just something to consume, or a very temporary pathway to being in the loop of a cultural moment or conversation.

K: It’s the liquidation of culture. You can put it in a blender and drink it down so fast. I’m not down for that. It’s easy to romanticise the past because we don’t usually reflect on the annoying elements of that previous time that technology has now solved for us. We just romanticise the aspects of our past that encouraged our ability to connect to art in a deeper way. When I think about not having the internet and listening to my Bob Dylan or The Killers CD in my bedroom when I was 16, that to me is romantic because it’s a moment where I was open to connecting with art on a deep level, without the intrusion of contemporary technology. We should be romanticising moments in the past when we were able to tap in with art in a deeper way. With the overload of data and choice that we have now, it can be more difficult to find meaning in experiencing and thoroughly investigating art. It’s the same with movies…you used to obsessively watch movies over and over again, and now the abundance of choice has somewhat negated that to a degree.